Mary Edwards Walker was no stranger to sneaking across enemy lines. When she wasn’t acting as a surgeon to tend to the Union wounded, she would sometimes enter Confederate territory — with armed escort and two pistols in her saddlebags — to deliver supplies to their hungry and deprived citizens. But one day, General William Tecumseh Sherman asked her to embark on a fundamentally different mission.

On April 10, 1864, Walker ventured alone into Confederate territory to gather information for a prospective Union campaign in Atlanta. She went forth unarmed, in order to appear peaceful in case she encountered the enemy. Soon, a group of Confederate soldiers discovered her. She offered them an alibi about delivering letters, but her blue surgeon’s uniform betrayed the truth. They took her as prisoner at gunpoint. It was the moment that would define her place in American history.

Walker underwent a week of travel before being interred in a Virginia prison, becoming an object of speculation and gossip. Her first burst of fame had come in 1862, when a New York Tribune field report mentioned a female war physician. “She can amputate a limb with the skill of an old surgeon, and administer medicine equally as well,” the paper wrote. “Strange to say that, although she has frequently applied for a permanent position in the medical corps, she has never been formally assigned to any particular duty.”

In1861, at the onset of the Civil War, Walker left her practice in Ohio to go to Washington D.C. There, she volunteered as a nurse in a makeshift hospital room in the U.S. Patent Office. She appealed to be a recognized Army surgeon, but despite garnering support from a few of her close supervisors, she was roundly rejected. Still, after a short stay in New York City to earn another degree, Walker came back to serve as a surgeon in Virginia on the battlefield.

Though unpaid and unacknowledged, Walker refused to give up her fight. She wrote to President Lincoln, expressing that the woman writing him “fully believes that had a man been as useful to our country as she modestly claims to have been, a star would have been taken from the National Heavens and placed upon his shoulder.” Lincoln replied five days later, but his letter, as follows, bore unhelpful news: “The Medical Department of the army is an organized system in the hands of men supposed to be learned in that profession and I am sure it would injure the service for me, with strong hand, to thrust among them anyone, male or female, against their consent.”

Walker continued to serve as a volunteer physician throughout 1862, conjuring for herself a blue uniform and trousers accented with a green surgeon’s sash. She opposed the medical staff’s heavy reliance on amputation, and reflected, “It was the last case that would ever occur if it was in my power to prevent such cruel loss of limbs.” This was in part from the direction of the sanitary commission, and in part, she suspected, because doctors wanted practice. In response to what she saw as a frequently reckless course of treatment, Walker would often communicate privately with soldiers to remind them of the option to decline the severe operation.

In late 1863, Walker was finally recognized as a surgeon, and given a salary of $80 a month. By the time of her capture in April of 1864, she had served in the battles of Bull Run, Chickamauga, Chattanooga, and Fredericksburg.

Walker’s capture was fodder for much publicity and conversation. Five days after, General Grant ordered all women to evacuate Union battlefields. On the Confederate side, soldiers and townspeople gawked at the “lady physician in bloomers.” “This morning,” wrote one Captain Benedict J. Semmes, “we were all amused and disgusted too at the sight of a thing that nothing but the debased and depraved Yankee nation could produce, a female doctor.”

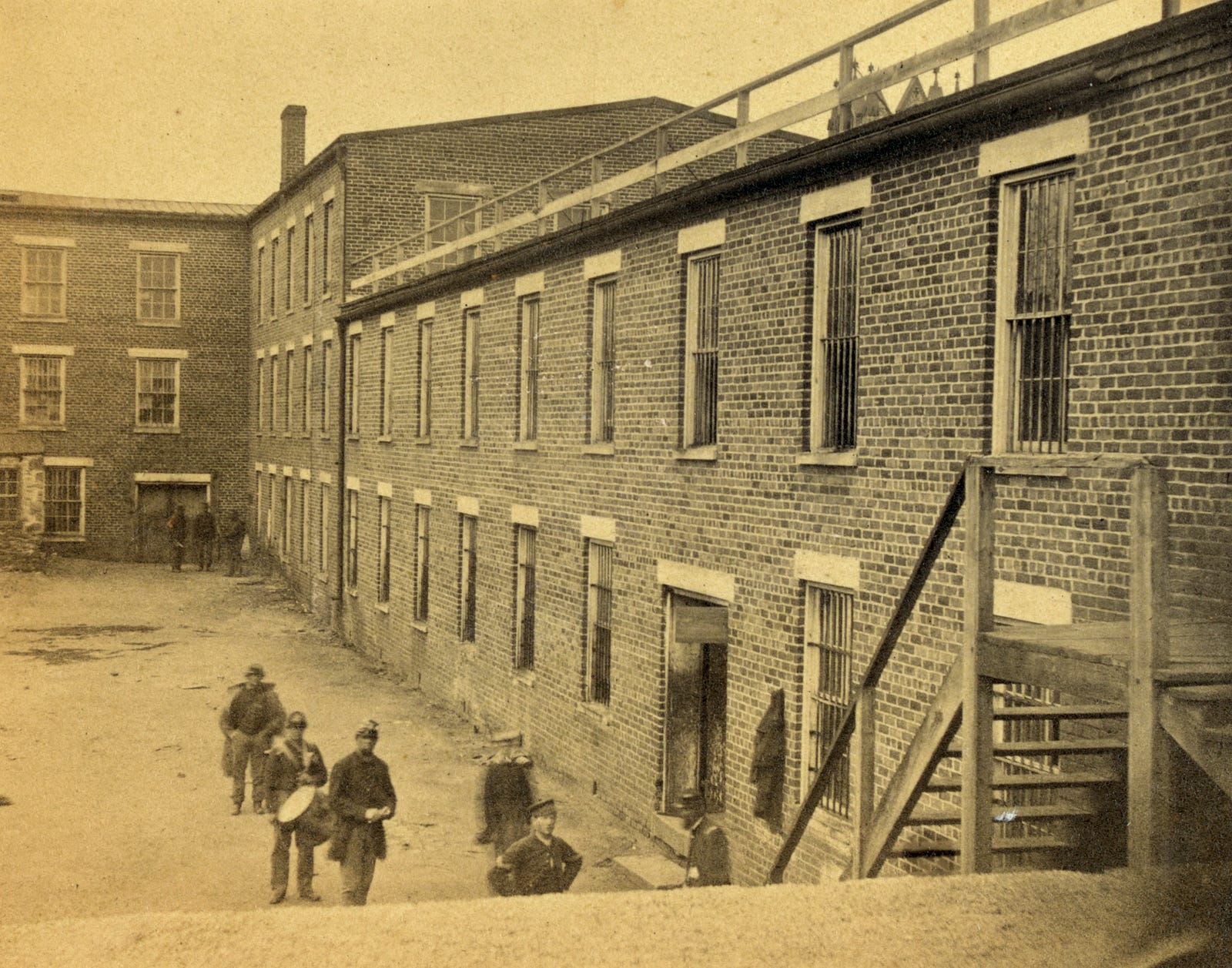

Walker was imprisoned at Castle Thunder near Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital. Thunder was a notoriously harsh and debilitating prison. Its cruel leader, George W. Alexander, was known to hang prisoners from their thumbs and flog them. One female spy was drugged, raped, and murdered there.

In one instance, Walker was standing in her doorway as a bullet whipped past her, nearly striking her skull. It came through her window, from a Confederate guard using her for target practice. Her room crawled with rats, and insects infested the straw of her mattress. Under these conditions, Walker became so malnourished that she suffered weakened eyesight and partial muscular atrophy from which she never fully recovered.

Still, she kept a reputation for her hardiness and defiance, and even demanded that the malnourished prisoners be fed wheat and fresh cabbage. She had, Captain Semmes recalled, “tongue enough for a regiment of men.”

Finally, in August, Walker was released as part of a prisoner exchange involving multiple physicians, with qualified medical help being scarce on both sides. “Miss Doctress, Miscegenation, Philosophical Walker, who has so long ensconced herself very quietly in Castle Thunder, has loomed into activity again,” wrote The Richmond Examiner upon her release.

Returning the battlefield, Walker was surprised to be paid $432.36 in salary from March to August 1864, having spent nearly all of that time captured. Her return came just in time for the Battle of Atlanta in September of 1864, for which her failed espionage efforts served to advance.

Walker would request to leave in June, 1865. The muscular atrophy incurred from her imprisonment effectively ended her career as a surgeon after the war. In November of that year, Walker received the Congressional Medal of Honor. Approved by President Andrew Johnson, the citation said Walker “has devoted herself with much patriotic zeal to the sick and wounded soldiers, both in the fields and hospitals, to the detriment of her health, and has endured hardships as a prisoner of war four months in a Southern prison.”

Thereafter, she took up the mantle of activism, and wrote and advocated for the female vote and dress reform. To the very end she agitated the conservative public with her masculine dress — wearing a top hat, bowtie, and a wing collar.

In 1917, in a motion blamed on a technicality and motivated by a desire to shrink the pension rolls, Walker had her Medal of Honor revoked with 910 other people. It’s rumored she continued to wear it until her death two years later. But in 1977, her commendation was restored under the Carter administration, and to this day, Walker remains the only woman to have been awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

–timeline.com