After being indoctrinated online into the world of white supremacy and inspired by a racist hate group, Dylann Roof told friends he wanted to start a “race war.” Someone had to take “drastic action” to take back America from “stupid and violent” African Americans, he wrote.

Then, on June 17, 2015, he attended a Bible study meeting at the historic Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston and murdered nine people, all of them black.

The act of terror shocked America with its chilling brutality.

But Roof did not spark a race war. Far from it.

Instead, when photos surfaced depicting the 21-year-old white supremacist with the Confederate battle flag — including one in which he held the flag in one hand and a gun in the other — Roof ignited something else entirely: a grassroots movement to remove the flag from public spaces.

In what seemed like an instant, the South’s 150-year reverence for the Confederacy was shaken. Public officials responded to the national mourning and outcry by removing prominent public displays of its most recognizable symbol.

It became a moment of deep reflection for a region where the Confederate flag is viewed by many white Southerners as an emblem of their heritage and regional pride despite its association with slavery, Jim Crow and the violent resistance to the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s.

The moment came amid a period of growing alarm about the vast racial disparities in our country, seen most vividly in the deaths of unarmed African Americans at the hands of police.

Under intense pressure, South Carolina officials acted first, passing legislation to remove the Confederate flag from the State House grounds, where it had flown since 1962. In Montgomery, Alabama — a city known as the Cradle of the Confederacy — the governor acted summarily and without notice, ordering state workers to lower several versions of Confederate flags that flew alongside a towering Confederate monument just steps from the Capitol.

The movement quickly began to focus on symbols beyond the flag. In Memphis, the City Council voted to remove a statue of Nathan Bedford Forrest, the Confederate general who oversaw the massacre of black Union soldiers and became a Ku Klux Klan leader after the Civil War. Months later, after a heated debate in December, the New Orleans City Council voted to remove three Confederate statues and another commemorating a bloody white supremacist rebellion against the city’s Reconstruction government in 1874.

Across the South, communities began taking a critical look at many other symbols honoring the Confederacy and its icons — statues and monuments; city seals; the names of streets, parks and schools; and even official state holidays. There have been more than 100 attempts at the state and local levels to remove the symbols or add features to provide more historical context.

Following the Charleston massacre, the Southern Poverty Law Center launched an effort to catalog and map Confederate place names and other symbols in public spaces, both in the South and across the nation. This study, while far from comprehensive, identified a total of 1,503.*

These include:

- 718 monuments and statues, nearly 300 of which are in Georgia, Virginia or North Carolina;

- 109 public schools named for Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis or other Confederate icons;

- 80 counties and cities named for Confederates;

- 9 official Confederate holidays in six states; and

- 10 U.S. military bases named for Confederates.

Critics may say removing a flag or monument, renaming a military base or school, or ending a state holiday is tantamount to “erasing history.” In fact, across the country, Confederate flag supporters have held more than 350 rallies since the Charleston attack.

But the argument that the Confederate flag and other displays represent “heritage, not hate” ignores the near-universal heritage of African Americans whose ancestors were enslaved by the millions in the South. It trivializes their pain, their history and their concerns about racism — whether it’s the racism of the past or that of today.

And it conceals the true history of the Confederate States of America and the seven decades of Jim Crow segregation and oppression that followed the Reconstruction era.

There is no doubt among reputable historians that the Confederacy was established upon the premise of white supremacy and that the South fought the Civil War to preserve its slave labor. Its founding documents and its leaders were clear. “Our new government is founded upon … the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition,” declared Confederate Vice President Alexander H. Stephens in his 1861 “Cornerstone speech.”

It’s also beyond question that the Confederate flag was used extensively by the Ku Klux Klan as it waged a campaign of terror against African Americans during the civil rights movement and that segregationists in positions of power raised it in defense of Jim Crow. George Wallace, Alabama’s governor, unfurled the flag above the state Capitol in 1963 shortly after vowing “segregation forever.” In many other cases, schools, parks and streets were named for Confederate icons during the era of white resistance to equality.

Despite the well-documented history of the Civil War, legions of Southerners still cling to the myth of the Lost Cause as a noble endeavor fought to defend the region’s honor and its ability to govern itself in the face of Northern aggression. This deeply rooted but false narrative is the result of many decades of revisionism in the lore and even textbooks of the South that sought to create a more acceptable version of the region’s past. The Confederate monuments and other symbols that dot the South are very much a part of that effort.

As a consequence of the national reflection that began in Charleston, the myths and revisionist history surrounding the Confederacy may be losing their grip in the South.

Yet, for the most part, the symbols remain.

The effort to remove them is about more than symbolism. It’s about starting a conversation about the values and beliefs shared by a community.

It’s about understanding our history as a nation.

And it’s about acknowledging the injustices of the past as we address those of today.

Findings & Map

It’s difficult to live in the South without being reminded that its states once comprised a renegade nation known as the Confederate States of America. Schools, parks, streets, dams and other public works are named for its generals. Courthouses, capitols and public squares are adorned with resplendent statues of its heroes and towering memorials to the soldiers who died. U.S. military bases bear the names of its leaders. And, speckling the Southern landscape are hundreds of Civil War markers and plaques.

The South even has its own version of Mount Rushmore — the Confederate Memorial Carving, a three-acre, high-relief sculpture depicting Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson on the face of Stone Mountain near Atlanta.

There is nothing remotely comparable in the North to honor the winning side of the Civil War.

For decades, those opposed to public displays honoring the Confederacy raised their objections, but with little success. A notable exception was a Southern Poverty Law Center suit that, relying on an obscure state law, led to the removal of the Confederate battle flag from the Alabama Capitol in 1993. Another was a 2000 compromise between South Carolina lawmakers and the NAACP that moved the flag from its perch above the Capitol dome to a monument on the State House grounds.

But everything changed on June 17, 2015 — just five days short of the 150th anniversary of the last shot of the Civil War.

That day in June, a white supremacist killed nine African-American parishioners at the “Mother Emanuel” church in Charleston, a place of worship renowned for its place in civil rights history.

As the nation recoiled in horror, photos showing the gunman with the Confederate flag were discovered online. Almost immediately, political leaders across the South were besieged with calls to remove the flag and other Confederate symbols from public spaces.

In the weeks that followed, it became clear that hundreds of public entities ranging from small towns to state governments across the South paid homage to the Confederacy in some way. But there was no comprehensive database of such symbols, leaving the extent of Confederate iconography supported by public institutions largely a mystery.

In an effort to assist the efforts of local communities to re-examine these symbols, the SPLC launched a study to catalog them. For the final tally, the researchers excluded nearly 2,600 markers, battlefields, museums, cemeteries and other places or symbols that are largely historical in nature.

Here are the most salient findings:

1. There are at least 1,503 symbols of the Confederacy in public spaces.

The study identified 1,503 publicly sponsored symbols honoring Confederate leaders, soldiers or the Confederate States of America in general. These include monuments and statues; flags; holidays and other observances; and the names of schools, highways, parks, bridges, counties, cities, lakes, dams, roads, military bases, and other public works. Many of these are prominent displays in major cities; others, like the Stonewall Jackson Volunteer Fire and Rescue Department in Manassas, Virginia, are little known.

2. There are at least 109 public schools named after prominent Confederates, many with large African-American student populations.

Schools named for Robert E. Lee are the most numerous (52), followed by Stonewall Jackson (15), Jefferson Davis (13), P.G.T. Beauregard (7), Nathan Bedford Forrest (7), and J.E.B. Stuart (5).*

The vast majority of these schools are in the states of the former Confederacy, though Robert E. Lee Elementary in East Wenatchee, Washington, and two schools in California (elementary schools named after Lee in Long Beach and San Diego) are interesting outliers.

Of these 109 schools, 27 have student populations that are majority African-American, and 10 have African-American populations of over 90 percent.

At least 39 of these schools were built or dedicated from 1950 to 1970, broadly encompassing the era of the modern civil rights movement.

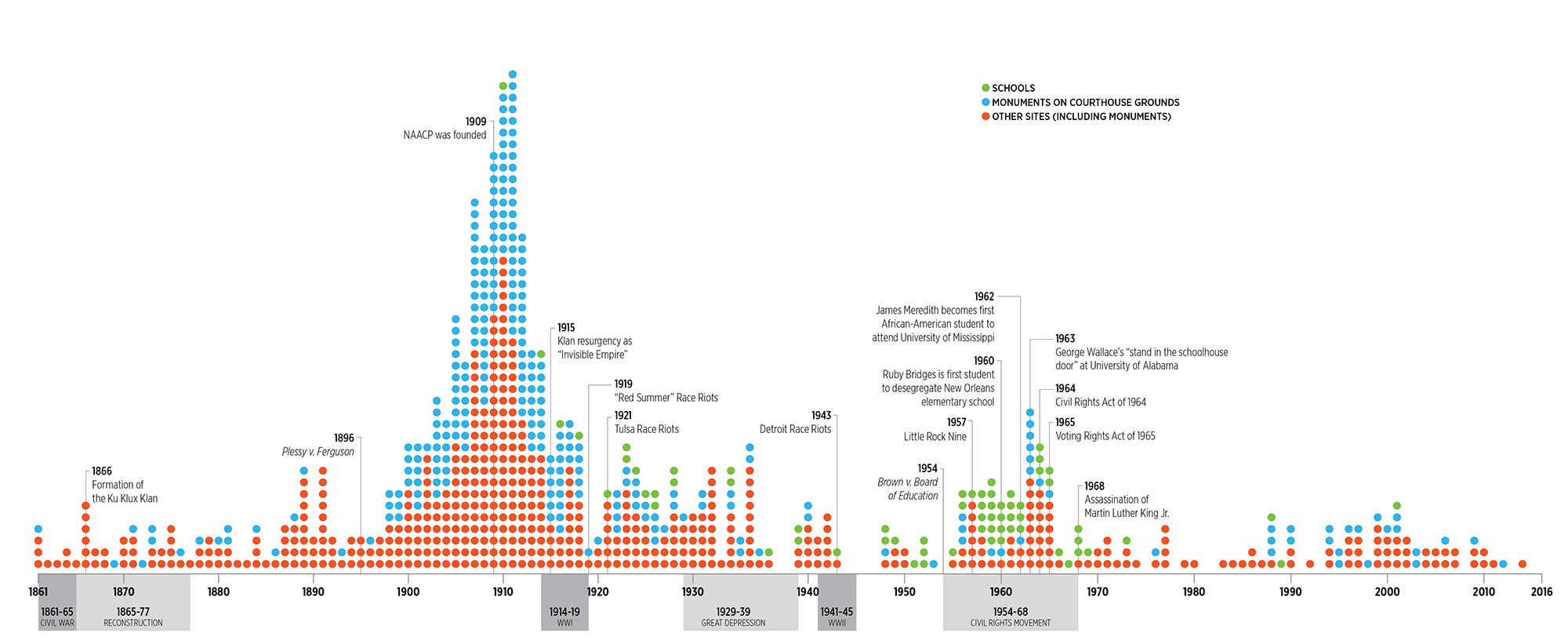

3. There are more than 700 Confederate monuments and statues on public property throughout the country, the vast majority in the South.

The study identified 718 monuments. The majority (551) were dedicated or built prior to 1950. More than 45 were dedicated or rededicated during the civil rights movement, between the U.S. Supreme Court’s school desegregation decision in 1954 and the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. The survey counted 32 monuments and other symbols that were dedicated or rededicated in the years since 2000.

Many of these are memorials to Confederate soldiers, typically inscribed with colorful language extolling their heroism and valor, or, sometimes, the details of particular battles or local units. Some go further, however, to glorify the Confederacy’s cause. For example, in Anderson County, South Carolina, a monument erected in 1902 reads, in part: “The world shall yet decide, in truth’s clear, far-off light, that the soldiers who wore the gray, and died with Lee, were in the right.”

Three states stand out for having far more monuments than others: Virginia (96), Georgia (90), and North Carolina (90). But the other eight states that seceded from the Union have their fair share: Alabama (48), Arkansas (36), Florida (25), Louisiana (37), Mississippi (48), South Carolina (50), Tennessee (43), and Texas (66).

These monuments are found in a total of 31 states and the District of Columbia. Outside of the seceding states, the states with the most are Kentucky (41) and Missouri (14), two states to which the Confederacy laid claim. Monuments are also found in states far from the Confederacy, including Arizona (2) and even Massachusetts (1), a stalwart of the Union during the Civil War.

4. There were two major periods in which the dedication of Confederate monuments and other symbols spiked — the first two decades of the 20th century and during the civil rights movement.

Southerners began honoring the Confederacy with statues and other symbols almost immediately after the Civil War. The first Confederate Memorial Day, for example, was dreamed up by the wife of a Confederate soldier in 1866. In 1886 Jefferson Davis laid the cornerstone of the Confederate Memorial Monument in a prominent spot on the state Capitol grounds in Montgomery, Alabama. There has been a steady stream of dedications in the 150 years since that time.

View and download a larger version of the timeline.

But two distinct periods saw a significant rise in the dedication of monuments and other symbols.

The first began around 1900, amid the period in which states were enacting Jim Crow laws to disenfranchise the newly freed African Americans and re-segregate society. This spike lasted well into the 1920s, a period that saw a dramatic resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, which had been born in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War.

The second spike began in the early 1950s and lasted through the 1960s, as the civil rights movement led to a backlash among segregationists. These two periods also coincided with the 50th and 100th anniversaries of the Civil War.

5. The Confederate flag maintains a publicly supported presence in at least six Southern states.

Last year, Confederate flags were removed from the capitol grounds of South Carolina and Alabama following the Charleston church massacre. However, the study identified nine public places in six former Confederate states where the flag still flies or is represented.

The most prominent is the Mississippi state flag, which conspicuously incorporates the Confederate battle flag into its design. In addition, emblems that adorn the uniforms of Alabama state troopers contain a likeness of the flag.

Also, there are four county courthouses where the flag still flies: Grady and Rabun counties in Georgia, Carroll County in Mississippi, and Walton County in Florida. In Victoria, Texas, the flag is part of a city park display that features six different national flags that have flown over the city.

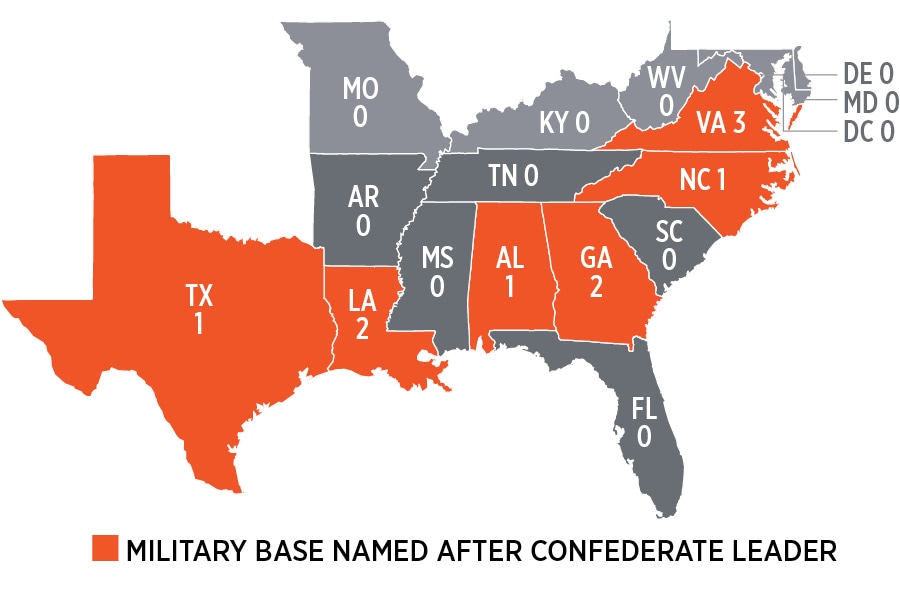

6. There are 10 major U.S. military bases named in honor of Confederate military leaders.

All of these bases are located in the former states of the Confederacy. They are Fort Rucker (Gen. Edmund Rucker) in Alabama; Fort Benning (Brig. Gen. Henry L. Benning) and Fort Gordon (Maj. Gen. John Brown Gordon) in Georgia; Camp Beauregard (Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard) and Fort Polk (Gen. Leonidas Polk) in Louisiana; Fort Bragg (Gen. Braxton Bragg) in North Carolina; Fort Hood (Gen. John Bell Hood) in Texas; and Fort A.P. Hill (Gen. A.P. Hill), Fort Lee (Gen. Robert E. Lee) and Fort Pickett (Gen. George Pickett) in Virginia.

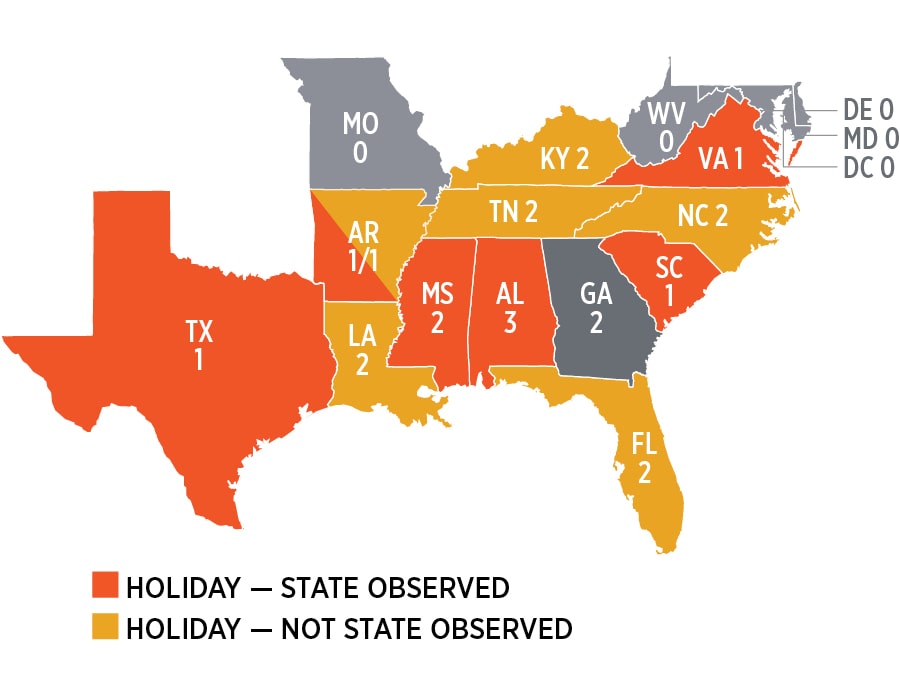

7. There are nine official Confederate holidays or observances in six Southern states.

Six states — Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, South Carolina, Texas and Virginia observe official state holidays that honor the Confederacy or its soldiers or leaders. Two states, Alabama and Mississippi, have at least two holidays in which state employees are given a day off.

Four other states — Florida, North Carolina, Kentucky and Louisiana — have Confederate holidays authorized in their state codes but do not officially observe them in 2016. In Tennessee, Confederate Decoration Day is subject to an annual proclamation.

Here are the nine holidays officially observed: Alabama (Robert E. Lee Day, Jefferson Davis’ Birthday, Confederate Memorial Day); Arkansas (Robert E. Lee Day); Mississippi (Confederate Memorial Day, Robert E. Lee’s Birthday); South Carolina (Confederate Memorial Day); Texas (Confederate Heroes Day); Virginia (Lee-Jackson Day).

Georgia struck Lee’s birthday and Confederate Memorial Day from its official state calendar in August 2015 and replaced the names with the term “state holiday.”

8. There have been at least 100 attempts at the state and local levels to remove or alter publicly supported symbols of the Confederacy.

Since the Charleston massacre, citizens in dozens of places across the country have taken action to address Confederate iconography. The most dramatic came on July 10, 2015, when the Confederate battle flag was removed from the South Carolina State House grounds in Columbia, ending its 53-year presence.

Some efforts have been highly contested, like in New Orleans, where the City Council voted to remove three statues honoring Confederate icons and another commemorating a racist militia that rebelled against the city’s Reconstruction government. Other efforts to rename streets, drop school mascots or redesign seals are ongoing. But legislators in some Southern states, including Alabama, are trying to enact laws to bar local officials from making decisions about these symbols.

The Confederate Flag

The Confederate battle flag is one of the most controversial symbols from U.S. history, recognizable by its red background and blue “X” adorned with 13 white stars. The stars represent the 11 Confederate states plus Missouri and Kentucky, two states that never officially seceded. It’s also sometimes called the rebel flag, Dixie flag or Southern Cross.

To many white Southerners, the flag is an emblem of regional heritage and pride. But to others, it has a starkly different meaning — representing racism, slavery and the country’s long history of oppression of African Americans.

The flag we see most often today is a rectangular version of the square battle flag that was flown by the Army of Northern Virginia, the South’s primary military force in the Civil War. But this was never the national flag of the Confederate States of America (CSA). In fact, from 1861 to 1865, the CSA adopted three different but similar versions — the Stars and Bars, the Stainless Banner and the Blood-Stained Banner. In addition, there were many other flags associated with various military units, including the Confederate States Navy.

It’s difficult to make the case today that the Confederate flag is not a racist symbol. After being used sparingly for decades, it began appearing frequently in the 1950s and 1960s as white Southerners resisted efforts to dismantle Jim Crow segregation. It began to fly over state capitols and city halls across the region. Elements of it were also incorporated into several state flags. Worst of all, it became a mainstay at Ku Klux Klan rallies as the organization launched a campaign of bombings, murders and other violence against African Americans and civil rights activists.

Today, the state flags of Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia and Mississippi still contain elements of the Confederate flag, with Mississippi’s being the most conspicuous.

Stone Mountain, Georgia

Stone Mountain Park, a Georgia state-owned park near downtown Atlanta, is known for the Confederate Memorial Carving, a massive mountainside sculpture depicting Confederate president Jefferson Davis and generals Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson on their horses. Stone Mountain is also known as the site of a 1915 cross-burning ceremony that marked the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan after a period of dormancy that began at the end of Reconstruction.

Billed as the largest high-relief sculpture in the world — larger than Mount Rushmore — the Confederate Memorial Carving stands 400 feet above the ground and covers three acres of the mountainside.

It was conceived in 1912 by a charter member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, a group that erected monuments across the South. The north face of the mountain was deeded to the organization four years later by its owner, who was closely associated with the Klan. An association established to oversee the work was stacked with Klan members.

The work began in 1922 but after various delays was abandoned for 36 years.

In 1958, during the civil rights movement, the state of Georgia acquired the property and created the Stone Mountain Memorial Association to oversee completion of the project. The carving was finally completed in 1972.

The desire to preserve slavery was the cause for secession by Southern states. But 150 years after the war, many continue to cling to myths. As recently as 2011, 48 percent of Americans in a Pew Research Center survey cited states’ rights as the reason for the war, compared to 38 percent citing slavery. This finding is all the more astonishing because a review of statements and documents by Confederate leaders makes their intentions clear. The following is a sample:

“We hold as undeniable truths that the governments of the various States, and of the confederacy itself, were established exclusively by the white race, for themselves and their posterity; that the African race had no agency in their establishment; that they were rightfully held and regarded as an inferior and dependent race, and in that condition only could their existence in this country be rendered beneficial or tolerable.”

Texas Declaration of causes for secession, February 2, 1861

“Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery — the greatest material interest of the world.”

Mississippi Declaration of causes for secession

“They assume that the negro is equal, and hence conclude that he is entitled to equal privileges and rights with the white man. If their premises were correct, their conclusions would be logical and just but their premise being wrong, their whole argument fails.”

Alexander H. Stephens, Vice President of the Confederacy

Cornerstone Speech, March 21, 1861

“Our new government is founded upon … the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.”

Alexander H. Stephens, Vice President of the Confederacy

Cornerstone Speech, March 21, 1861

“A geographical line has been drawn across the Union, and all the States north of that line have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States, whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery.”

South Carolina Declaration of causes for secession,

December 24, 1860

In researching publicly supported spaces dedicated to the Confederacy or its heroes, SPLC researchers relied on federal, state and private sources. Each entry was verified by at least one other source. When possible, preference was given to governmental sources over private, less-reliable ones.

For federal databases, researchers used the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), the National Park Service, and the National Register of Historic Places. Researchers created a list of prominent Confederate heroes and identified municipalities, counties, schools, buildings, monuments, military bases, parks and other spaces named for them. Each entry was cross-referenced with municipal, county or school district websites in an attempt to confirm that spaces were named for the Confederacy or its heroes and did not coincidentally share a name. In some instances, this confirmation was not possible and some ambiguous spaces were included.

Researchers also used state government resources, such as state historical commissions and similar agencies. The information available through these sources was inconsistent across states. Some, such as North Carolina, have comprehensive databases, while others, such as Louisiana, have very limited information.

The Smithsonian’s Art Inventory is a comprehensive database of art in the Smithsonian collection and in public spaces. A search of “confederate” limited to “outdoor sculpture” primarily resulted in a database of monuments on public property. Most of the monuments found in this search were added to Smithsonian’s database through a survey campaign in the early 1990s by an organization called Save Outdoor Sculpture. Because many of these entries originated with the general public, they were verified with at least one other source.

The search also led to many private databases with information about markers and monuments across the country. There is a large community of people online who are dedicated to documenting public markers and monuments. The most popular sites for these communities appear to be Waymarking, a membership-based database of historical markers in which members can post historical sites and markers they have visited; the general public can search this database, and each entry includes a photograph and GPS coordinates. The Historical Marker Database is another database with entries that are submitted by the general public and confirmed by an editor.

In addition, many regional private organizations dedicated to honoring the Confederacy, including Sons of Confederate Veterans and Daughters of the Confederacy, maintain online databases of local and regional monuments and sites. Some state historical societies also offered useful data.

As the interest in documenting and confronting the celebration of the Confederacy grows, an increasing number of national and local journalists are writing about monuments, markers, and locations named in honor of the Confederacy. Researchers used these articles to verify and supplement information.

–splc.com