TENNESSEE: Flag’s Stars Tell Unique History

NASHVILLE — Eagle-eyed visitors to Nashville’s Civil War-era Fort Negley may have noticed something a little bit different about the United States flag that flies near the visitor’s center.

As Topher Fleming asks:

Why is there a 35 star flag flying over Ft Negley?

The simple answer is the 35 stars represent how many states there were at the time of the Civil War — just as the 50 stars on today’s flag stand for the 50 states.

But Krista Castillo, the museum coordinator at Fort Negley, says the flag tells a deeper story about Nashville during the conflict.

“I think it’s a great example of psychological warfare. You know they put this huge flagpole on top of a hill that looms down on the city. The fort was bristling with cannons. And then they top it off with the biggest American flag they could find.”

No one knows exactly how big the flag over Fort Negley was, but sketches and photographs taken during the Civil War show that the flag was huge, says Castillo. It flew atop a flagpole that soared 80 feet in the air.

The flagpole itself was sited at the highest point in Fort Negley, and the fort stood 260 feet above the Cumberland River.

The flag would have been one of the most visible sights in Nashville. Only the Tennessee State Capitol would have rivaled it. And it, too, flew the American flag.

“There was no misconception about who was in control,” says Castillo.

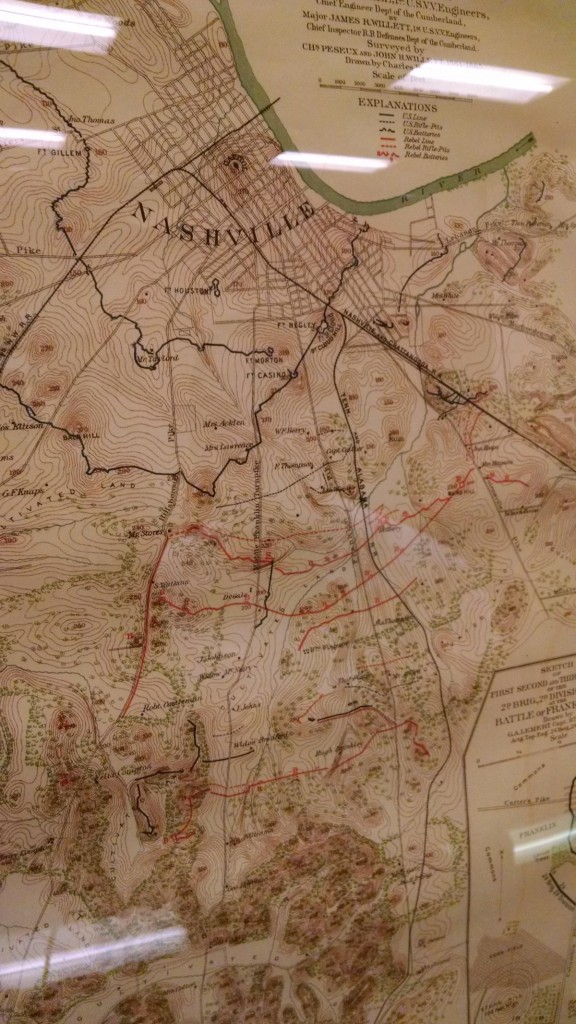

A map at the Fort Negley visitors center shows the fortifications around Nashville during the Civil War.

CREDIT CHAS SISK / WPLN

There were actually only 34 stars on the American flag when Nashville surrendered to Union forces in January 1862, less than a year after the outbreak of the Civil War. The number didn’t go to 35 stars until 1863, when West Virginia was added to the Union, and it increased again to 36 stars two years later with the addition of Nevada.

All three flags likely flew over Fort Negley.

Strategic Importance

Nashville was the first Confederate state capital to fall, surrendering to Union forces in January 1862, less than a year after the Civil War began. But all was not peaceful after that. For the next several months, Nashville was a besieged city, says Castillo.

Union and Confederate troops skirmished frequently outside Nashville’s borders, prompting the Union to build a chain of forts around the city’s perimeter. Construction on Fort Negley began in August 1862.

The fort was placed on a hill near three of the major roads into Nashville — Murfreesboro Pike, Nolensville Pike and Franklin Pike — and overlooking the convergence of several railroad lines, as well as a large depot. The location also gave Union forces a clear view to the south.

“Between the two bastions, at least I’m told by our signal corps historians, on a clear day you can 30 miles,” says Castillo, “and it’s a pretty impressive view to the south.”

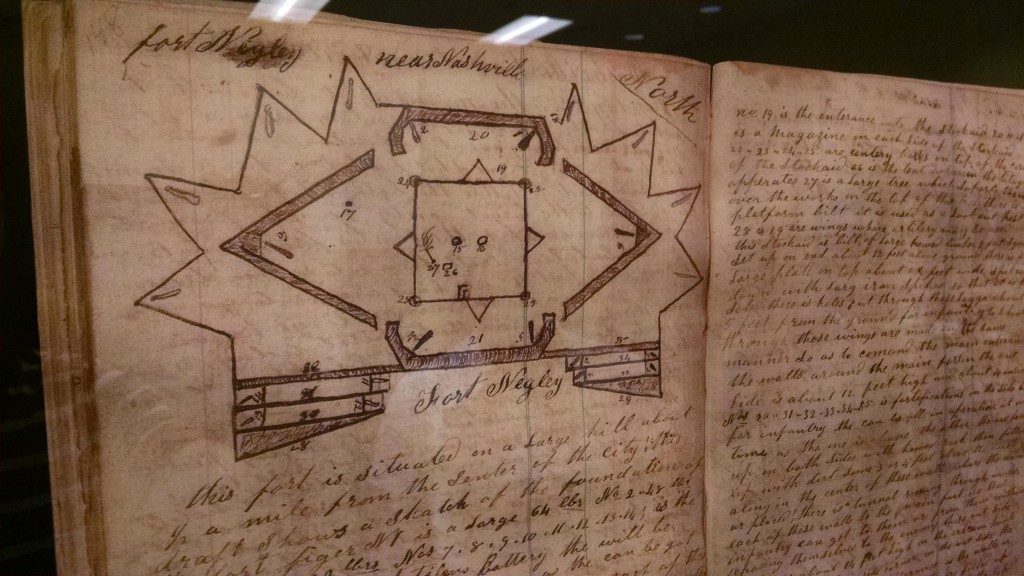

An early sketch of the layout of Fort Negley shows the compound would bristle with heavy artillery. Much of it was shipped upriver from naval vessels.

CREDIT CHAS SISK / WPLN

Confederate commanders recognized the Union would have a much firmer grip on Nashville if Fort Negley were completed. While the fort was still under construction, Confederate Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest attempted in November, 1862 to retake the city with about 1,000 cavalrymen. They were beaten back — thanks in part, Castillo says, to the artillery already in place at Fort Negley.

The fort was finished the next month and named after commander James Scott Negley. Its opening would usher in a period of relative calm. Confederate forces wouldn’t threaten Nashville again until December 1864. In a last-ditch effort to turn the tide of the war, General John Bell Hood marched on the city, setting up camp in what is now Green Hills.

But Hood had no intention of trying to conquer Fort Negley directly. He was badly outnumbered and hoped to lure Union forces out in the open. And after a two-week standoff, Union soldiers finally did march out of the city, setting off the fighting that would come to be known as the “Battle of Nashville.” The Union won handily, driving the rebel forces back.

“The Battle of Nashville gets most of the hype. In my opinion, the narrative, the story is the occupation of Nashville, and the battle is that exclamation point,” says Castillo.

“We often hear from visitors: Well if the fort wasn’t attacked, what’s the point? But that’s exactly the point. The fort was meant to look so frightening that people wouldn’t want to attack the city. And it worked.”

In Civil War-era Nashville, Fort Negley was the ultimate embodiment of force. And the big American flag at the fort’s top was the ultimate reminder that the Union called the shots.

–nashvillepublicradio

###

NEW YORK: Cornell to Drop ‘Plantations’ From Name of Garden After Protest

ITHACA, N.Y. — Cornell University announced last week that it is changing the name of the Cornell Plantations to the Cornell Botanic Gardens.

The university announcement stressed that the new name better reflects the 4,000 acres of natural landscape and natural history collections that have made up the Cornell Plantations. But the name of the Cornell Plantations has also been criticized by many minority students on the campus, who view the word “plantations” as associated with slavery, even if the land and programs that makes up the Cornell gardens never had any association with slavery. Last year, Black Students United demanded a new name for Cornell Plantations as one way Cornell could be more inclusive of its minority students.

Cornell officials who have been reviewing the identity of the Cornell Plantations said that its name is inconsistent with its activities. Christopher Dunn, director of the Cornell Plantations, said he viewed “plantation” as being about a single crop. “A botanic garden is all about showcasing the rich diversity of the plant kingdom. How can you have a plantation that is a botanic garden? It’s a non sequitur,” he said in the university announcement.

He also noted that many people associate the word plantations with slavery. And the announcement quoted Ryan Lombardi, vice president for student and campus life, saying: “Renaming Cornell Plantations not only respects the richness of this great natural and scientific resource, it shows our full respect for the diverse and highly valued community of students and scholars this university is fortunate enough to serve.”

Changing Names

Many colleges and universities have been debating what to do about buildings, statues or inscriptions that praise the Confederacy or its supporters. This summer has seen changes at several universities:

- The University of Texas at Austin moved a panel in a prominent campus location with an inscription that praises “the men and women of the Confederacy who fought with valor and suffered with fortitude that states’ rights be maintained” and who were “not dismayed by defeat nor discouraged by misrule.”

- Vanderbilt University announced that it will pay the Tennessee chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy $1.2 million (the value in today’s dollars of a gift from the group in 1933) so the university can legally remove the word “Confederate” from Confederate Memorial Hall, built in part with that gift.

- Yale University, three months after announcing it would keep the name of the slavery advocate John Calhoun on one of its residential colleges, announced a process to reconsider, and to possibly remove, the name.

The Cornell Plantations name is in some ways different from the other examples. The panel at Texas and building name at Vanderbilt were intended to honor the Confederacy. The college at Yale honors one of the most effective politicians of his era at preserving slavery and promoting racist views. In contrast, the Cornell Plantations were never intended to honor slavery. In some ways the debate is similar to the one at several colleges that led them to drop the word “master” (for leader of residential college). The origins of the word have nothing to do with slavery, but the word has come to be associated with it.

Language experts say that the word plantations is associated with slavery, but also has roots that are about plants, not slavery.

The name ended up on the Cornell gardens specifically as a way to promote a non-slavery meaning. The horticulturist Liberty Hyde Bailey named the Cornell Plantations in 1944, and according to a profile in the Plantations’ magazine, “he purposely chose to dismiss old associations with slavery in favor of the proper meaning of the word, plantations: ‘areas under cultivation’ or ‘newly established settlements.’ ”

Reactions to the Change

Cornell surveyed supporters of the Cornell Plantations and found overwhelming support for changing the name.

People weighing in on the website of The Cornell Daily Sunhave expressed a range of views. One alumna wrote of assuming from the Cornell Plantations name that it was a site of crop research, and said that it took her a while to discover what was really there — and to enjoy visits there. She said the name change was “sensible.”

Another wrote: “As long as people can still trip and enjoy the trees I don’t care what it’s called.”

Others, however, wrote that there was no reason to change the name. One alumnus wrote: “You mean it’s NOT a slaveholding operation? I had no idea — THANK YOU for changing the name and making that clear to me. (Ridiculous — just ridiculous.)”

And another wrote: “A monstrous betrayal of generations of Cornell alumni attached to the Cornell Plantations. And for what? To appease a handful of crybabies who can’t read a history book or a map, given that they can’t tell the difference between the Cornell Plantations and an agricultural model practiced 150 years ago a thousand miles south of Ithaca. This university administration needs to start standing for something other than appeasement, retreat, and milquetoast nonsense. Can everyone just grow up now? The world doesn’t pander, and Cornell shouldn’t either.”