MARYLAND: Mayor Calls for Removal of Confederate Historical Marker

The peaceful lawn of the historic Wicomico County Courthouse with its tall, old shade trees and brick walkways seems an unlikely place for a controversy to be brewing.

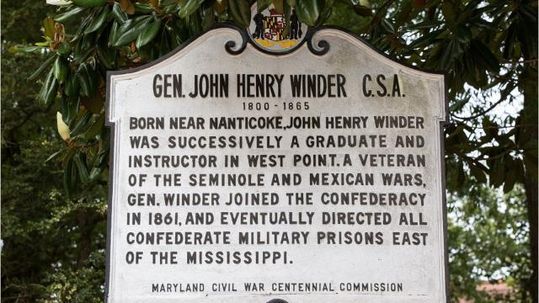

A view of a placard memorializing Confederate Gen. John Henry Winder on Wednesday, June 14, 2017. (Photo: Staff photo by Ralph Musthaler)

Most of the drama over the years has happened inside the 1870s structure.

But a historical marker on the property recognizing a Confederate general is renewing the rift between North and South.

James Yamakawa of the group Showing Up for Racial Justice wants the marker commemorating Gen. John Henry Winder removed from the courthouse property, which is the site of the former Byrd Tavern where slaves were kept prior to be auctioned off.

“A marker honoring a Confederate general, a person who supported the cause of slavery, sits within easy view of where black Americans were once treated like cattle waiting to be bought,” Yamakawa said in a petition he started on Change.org.

To make matters worse, the courthouse also is near where the lynching of Matthew Williams took place in 1931, he said.

Williams, a black man suspected of shooting his white employer, was removed from a bed at Peninsula Hospital by a white mob and dragged to the courthouse where he was hung from a tree. Afterward, his body was dragged to the city’s black community, tied to a lamppost, doused with gasoline and set on fire.

Others in the community like Stephen Hall of Salisbury think the marker should say put, and they denounce efforts to remove Confederate monuments in New Orleans and other U.S. cities.

IN DEFENSE: Salisbury Confederate marker finds support in petition

“This is an outrage,” he said. “Should we destroy the history of the Confederacy?”

Hall also argues that the Civil War was fought over states rights, not slavery.

The call to remove monuments and symbols of the Confederacy has taken hold across the country following the 2015 shooting inside a black church in Charleston, South Carolina, but it has sparked angry protests throughout the nation.

The Confederate battle flag was removed from the South Carolina state capitol, and the National Park Service removed Confederate flags, T-shirts and other memorabilia from gift shops at Civil War sites across the country soon after the shootings.

More recently, the city of New Orleans began removing its Confederate monuments in April. A controversial move that has sparked protests and death threats.

BACKGROUND: New Orleans begins removing Confederate monuments

In Maryland, the state Motor Vehicle Administration has stopped issuing license plates bearing the Confederate battle flag, and legislators introduced a bill to remove a statue from the Statehouse grounds of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, author of the Dred Scott decision.

Closer to Salisbury, the Talbot County NAACP called for the removal of the “Talbot Boys” monument on the Talbot County Courthouse lawn in Easton that honored 85 county residents who fought for the South. Last year, the Talbot County Council voted unanimously to leave the monument in place because it honors veterans, according to news reports.

READ MORE: Confederate questions remain in Maryland

Salisbury Mayor Jake Day, who signed the petition to remove the Winder marker from the Wicomico County Courthouse, said all history should be acknowledged but it should be accurate.

“Every marker on battlefields in Gettysburg, Antietam or elsewhere is painstakingly placed,” he said. “Gen. Winder has no connection to Salisbury. He is from Nanticoke. His sign belongs there, if anywhere.”

Hall said he is angered over efforts in Salisbury and across the country to get rid of tributes to people who fought for the South.

“What’s next?” he said. “Is every liberal mayor going to remove all the Confederate monuments?’

The marker

The historical marker in question was never intended to be placed at the courthouse, or on any county property.

In 1965, the sign was erected on South Salisbury Boulevard near the Messick Ice Plant by the Wicomico County Historical Society and Maryland Civil War Centennial Commission, according to research by local historian Linda Duyer. The ice plant is now the home of the Evolution Craft Brewing Co.

After the sign was knocked over a few times in traffic accidents on the busy roadway, it eventually was moved to the courthouse lawn. The Wicomico County Council approved the request by the Sons of Confederate Veterans to move it, and a dedication was held Sept. 25, 1983, according to newspaper reports.

Another marker commemorating Confederate Gen. Arnold Elzey was placed by the Civil War Centennial Commission in the Somerset County village of Oriole near Elzey’s home Elmwood, according to a list of historical markers on the Maryland Historical Trust website.

The signs for Winder and Elzey — both of whom graduated from West Point and served in the U.S. Army prior to 1861 — are the only historical markers commemorating members of the Rebel army on the Lower Shore.

The controversy over the placement of the Winder sign is nothing new. In 2014, Edward T. Taylor, a former member of the Wicomico County Council, called for its removal in a letter published in The Daily Times.

Winder, who was given command of all military prisons in Alabama and Georgia, was blamed for the mistreatment and deaths of Union soldiers held there, he said.

“Commemorative markers on public courthouse lawns such as this should be reserved for national heroes whose life and national contributions are celebrated,” Taylor said.

READ MORE: Courthouse lawn is our ‘seat of honor’

Duyer wrote a letter of support for Taylor at the time, and said she still thinks the historical marker should be removed from the courthouse property.

“My personal preference is to get rid of anything on the lawn, including the cannon,” she said. The Gen. Humphreys Cannon commemorates the War of 1812.

County Council President John Cannon said the county hasn’t taken any steps one way or the other.

“At this stage, I don’t know whose purview this falls under,” he said.

The general

Winder was born in 1800 at Rewston, a plantation near Nanticoke in what was then still part of Somerset County.

After graduating from West Point, Winder served in the U.S. Army and was a veteran of the Mexican War, but he resigned his federal commission in April 1861 with the start of the Civil War, according to the National Park Service.

Winder was appointed provost marshal and commander of prisons in Richmond and later was given command of all military prisons in Alabama and Georgia, including the prison at Andersonville, a stockade built to hold a maximum of 10,000 Union Army prisoners, according to the park service which operates the Andersonville National Historic Site.

“At its most crowded, it held more than 32,000 men, many of them wounded and starving, in horrific conditions with rampant disease, contaminated water, and only minimal shelter from the blazing sun and the chilling winter rain. In the prison’s 14 months of existence, some 45,000 Union prisoners arrived here; of those, 12,920 died and were buried in a cemetery created just outside the prison walls,” according to the Andersonville website.

Under Winder’s command was Capt. Henry Wirz who was later charged with violating the laws of war by withholding food and supplies to prisoners, resulting in their deaths. At a military tribunal, Wirz claimed he was only following orders, but he was convicted of conspiracy and murder and hanged in 1865. Winder died of a heart attack the same year.

“In all probability, the responsibility for the conditions at Andersonville should fall on the Winder’s shoulders as much as on Capt. Wirz,” according to the National Park Service.

Day said he thinks Winder’s sign also should include “that he is a war criminal who tortured and killed American soldiers as POWs.”

“There are so many historical figures who have impacted the course of history here that actually have a connection to Salisbury,” he said. “And if we should acknowledge anyone in the center of the city, why would it be someone who is not connected to this place?”