A popular misconception of the American Civil War is the view that mounted charges against infantry were an outdated tactic. The image of charges being ordered by out-of-touch generals that did not comprehend that rifled muskets had changed combat is a common one. While the Civil War produced many instances of cavalry charges that failed against infantry, these have been sometimes overemphasized by historians as an argument for the effectiveness of the rifled musket. By examining the actions of Federal cavalry mainly associated with the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps, a more nuanced view of cavalry charges emerges.

Perhaps two of the most widely known cavalry charges against infantry are the 5th U.S. Cavalry charge at Gaines Mill and the Farnsworth Charge at Gettysburg. Both charges ended in failure and both have been used by historians as examples of outdated tactics that caused unnecessary casualties. While the emphasis on the cause of the failure has usually been the fire coming from rifled muskets, both charges got well within 100 yards before being repulsed, well within the range of smoothbore muskets. The main reason that both charges failed is not from the use of rifled muskets (again smoothbore muskets would have easily repulse these charges, and in fact some of the Confederates that threw back these assaults were still armed with smoothbore muskets), but that the infantry was alert and ready for the charge.

When infantrymen were not ready to receive an assault, a small cavalry charge could be temporarily successful, as was the case of the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry at Cedar Mountain. Towards the end of the battle, one squadron (2 companies) of Pennsylvanians were ordered to charge a battery that was captured by surging Confederates. Thundering down the Culpepper Road, the blue clad horsemen were able to break the Confederate line. However, since the Federals were outnumbered, they were quickly sent galloping back the way they came. The failure of this charge was not from the effectiveness of the rifled musket, but because of the small number of cavalrymen that were sent into the charge. Three examples of Federal cavalry charges during the last year of the war show that mounted charges could be successful, even decisive, if enough troopers were engaged.

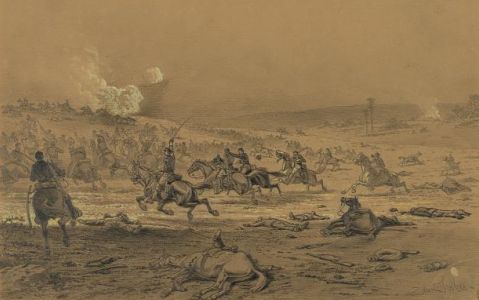

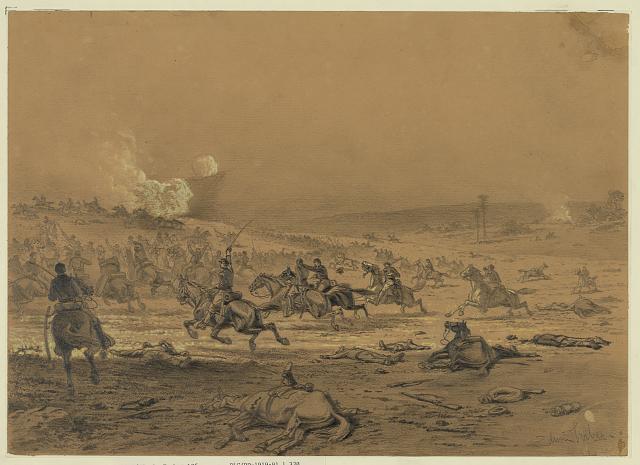

By 1864, the Federal cavalry in Virginia was nearing the pinnacle of power. Not only were the majority of the troopers veterans armed with modern weapons (including the Spencer carbine) but more importantly the majority of officers all the way up through the chain of command were prepared by experience and temperament on how to effectively use cavalry. At the end of the Third Battle of Winchester in September 1864, a couple divisions of Federal cavalry were thrown against the left of the Confederate line at exactly the right time to help rout the rebel army from the field of battle. A few weeks later in the Shenandoah Valley at the Battle of Cedar Creek, Federal cavalry again decisively aided in the rout of a Confederate army by a mounted charge against both flanks of the rebels.

In the final week of the war at the Battle of Sailor’s Creek, a mounted charge by Federal cavalry against partially entrenched Confederate infantry not only succeeded, but steamrolled over the rebels capturing many prisoners and making the rest combat ineffective for the rest of the campaign. Although many Confederates were demoralized during the Appomattox Campaign, low morale was not the primary reason for the success of the mounted charge. On other parts of the battlefield, Confederate infantrymen were not only able to stop a Federal infantry attack, but launch their own counterattack that was finally thrown back after heavy casualties. Later in the campaign closer to Appomattox Courthouse, portions of Lee’s army still showed a willingness to engage the enemy.

If mounted assaults could be decisive, as was the case during the last year of the war, why weren’t more charges successful? While rifled muskets could damage a cavalry charge the success and failure of a charge boiled down to two factors. First, the cavalry had to be used at the right time. Against infantrymen who were organized and still had their morale, a mounted charge often was little more than an exercise in organized suicide, such as Farnsworth’s Charge or the charge at Gaines Mill. Secondly, once the cavalry was engaged, they had to be used in adequate numbers to keep the momentum and prevent the infantrymen from rallying. A perfect example is the 1st Pennsylvania at Cedar Mountain; even though the troopers broke through the rebel line, there were not enough of them to keep the Confederates from rallying and throwing them back. A cavalry charge was a one-shot weapon and its success depended on the commander knowing when to commit the charge at the decisive point at the decisive time. By 1864, Federal cavalry was finally concentrated in sufficient numbers and commanded by men who knew when and where to mount a charge. The results were multiple cavalry charges that were wildly effective against veteran infantrymen equipped with rifled muskets.