Jimmy Kerr points to the indigo stains on the walls of an old indigo vat on his Johns Island property. Brad Nettles/Staff

When Jimmy Kerr was a boy, he was playing cowboys and Indians with buddies when he stumbled across an old brick foundation nestled deep into the woods on his family’s Johns Island land.

For many years, his family thought the bricks were all that was left of some sort of small, long-vanished outbuilding. It wasn’t until 2009, after Kerr hired cultural resource experts as part of planning their land’s future use, that they discovered the site’s link to one of South Carolina’s most important cash crops.

The “foundation” is, in fact, a rare surviving indigo vat — a series of pools for processing indigo dye.

So what once was thought to be a potential source of scrap bricks is expected to become a focal point as this property is developed under a plan Charleston City Council recently approved.

“It will become a neighborhood treasure, if you will, rather than being lost in the woods for who knows how many years,” Kerr said.

Kind of blue

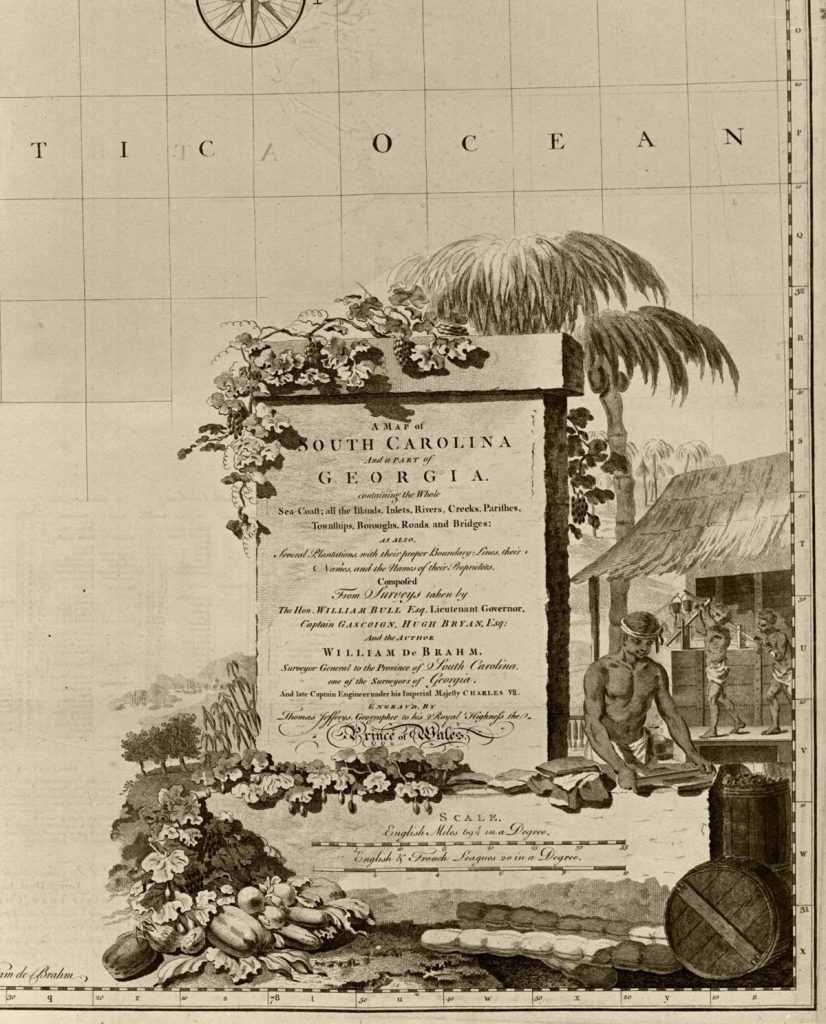

The earliest South Carolina colonists experimented with growing indigo but couldn’t create anything that could compete with dye made in the West Indies, according to historian Virginia Jelatis, author of “Tangled Up in Blue: Indigo Culture and Economy in South Carolina 1747-1800.”

That changed when a Charleston teenager named Eliza Lucas began experimenting with growing indigo in the late-1730s. She found some success and shortly afterward married Charles Pinckney, who promoted the crop in London. Parliament ultimately agreed to subsidize Carolina indigo production in 1749.

While rice remained the Lowcountry’s dominant cash crop, indigo would serve as a nice complement and could be planted just behind rice fields on the slopes.

“The crop could be grown on land not suited for rice and tended by slaves,” Jelatis wrote, “so planters and farmers already committed to plantation agriculture did not have to reconfigure their land and labor.”

In 1747, 138,300 pounds of dye were produced in the colony, and indigo peaked in 1775 with 1.12 million pounds valued at 242,395 pounds sterling, more than $40 million in today’s money. Most all of it was shipped to England.

The Revolutionary War disrupted the crop and American independence ultimately caused its local demise.

“No longer part of the British Empire, South Carolina indigo growers lost their bounty and market as England turned to India to supply its indigo demand,” Jelatis wrote.

By 1802, it no longer was listed among the state’s exports.

Not much survives

As the market dried up, there was little use for the series of vats built especially to process the dye.

These processing sites included an upper vat, also called a “steeper vat,” where the indigo plants were fermented. The resulting liquor then was drawn from the “steeper vat” into a lower “beater” or “battery” vat, where it was agitated. Water was drawn off, exposing a sludge that was strained, molded into cakes and dried.

By 1979, South Carolina’s only known surviving indigo vats were in Otranto Plantation in Berkeley County, which was being redeveloped as a subdivision.

Of its three series of vats, two were considered too deteriorated to save, but one was broken into big chunks, moved and reassembled at its current site off Bushy Park Road, in front of the Bayer Heritage Federal Credit Union.

The surviving site includes two square brick vats, 14 feet by 14 feet, placed end to end and stuccoed on the inside. When it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1989, its nomination form noted it was the only such structure known to exist in the state.

But since then, a 1994 survey of the Charleston Naval Weapons Station identified remnants of an 18th century indigo vat there, and a tabby indigo vat was documented in 1997 at Burlington Plantation in Beaufort County, said Elizabeth Johnson of the State Historic Preservation Office.

Johnson said a 2006 Georgetown County historic survey noted the importance of indigo there, but it doesn’t note any surviving vats.

The Johns Island find in 2009 marks the state’s fourth known example. Like the vats at Burlington, it has four square brick chambers, two of which are a few feet higher than the lower ones.

“I don’t know whether it’s a four-step process or a duplex,” Kerr said. An archaeologist’s report says they’re likely a pair built by planter Edward Fenwick.

And like those at Otranto, their insides have some stucco surviving, and a close look reveals a trace of a blueish hue.

A dyeing art

Of course, indigo never really went away, said Brian Ward, a research scientist with Clemson’s College of Agriculture, Forestry and Life Sciences.

“I still have seed that’s over 250 years old of the original indigo that was grown here,” he said. “I’ve done research on it for a number of years.”

The plant itself is still grown in smaller amounts as an ornamental plant, for historical interpretation and as a niche business.

Ward said he’s talked to some landowners interested in growing it commercially, but the conversations didn’t lead anywhere.

“One of the issues from keeping it from getting bigger is we don’t have the labor to pick it,” he said.

On some Sea Islands, where the temperature rarely dips below freezing, indigo can survive as a perennial plant.

“Even there, it can get frosted and still come back,” Ward said.

One of the few public places people can see indigo today is at Middleton Place, which grows and processes a small amount to help explain the crop’s former significance to the Middleton family, said Jeff Neale, director of Middleton’s preservation and interpretation.

“We do not have any evidence of indigo being grown at Middleton Place, nor are they any vats located on the property. However, we do know that indigo was the main product of both the Wassamsaw and Wampee plantations, which were owned by the Middletons in the mid-18th century,” he said.

Most visitors passing by the indigo crops growing in the stable yards area or in Middleton’s demonstration garden probably won’t recognize what it is.

“Green plant, pink blooms, and it makes the color blue,” Neale said. “It doesn’t make sense.”

Neale said these plants produce enough to make a few pounds of indigo bricks. He and Middleton’s staff use vats that measure only about 2 feet by 4 feet, a fraction of the size of the vats used in indigo’s heyday.

Those interested might see some being processed there in August, and the resulting dye will be used to make light blue items for sale in Middleton’s gift shop.

As for other blue clothes sold today, most are dyed with a modern chemical process developed in a lab — one that’s perhaps more humane, efficient and inexpensive but one unlikely to ever leave as intriguing a footprint on the land.

–postandcourier.com