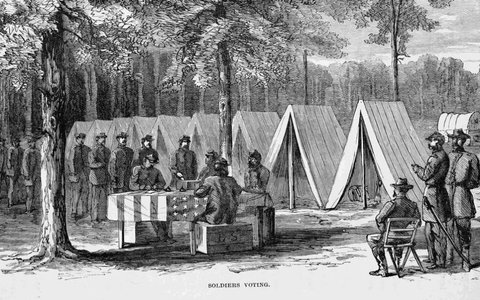

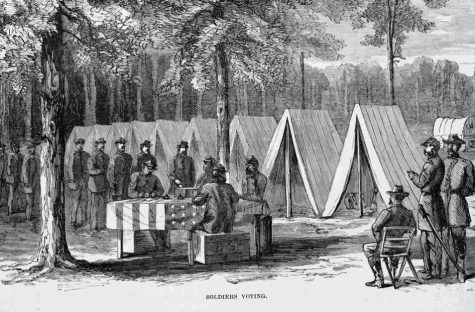

When soldiers living in Civil War encampments wanted to cast their vote for Republican incumbent Abraham Lincoln or Democrat George McClellan in the 1864 election, most were able to follow the same steps as their parents back home. Lists of registered voters were filled out on the battlefields. De facto election judges and clerks were plucked from the gathered troops. From Kentucky to Vermont, voting rights were extended to those far away from the polls for the first time—though not without significant legal challenges and public skepticism.

During the Civil War, typical voting processes were replicated on battlefields of 14 states. Six additional states allowed soldiers to mail in their ballots back home. Here, an illustration shows Union Army soldiers lined up to vote on November 8, 1864. Republican incumbent Abraham Lincoln won the election.

ILLUSTRATION BY INTERIM ARCHIVES, GETTY IMAGES

More than a century and a half later, as the United States grapples with a pandemic and an upcoming presidential election, voting by mail has again taken center stage. On Thursday, President Donald Trump told Fox News that he opposes additional funding for the U.S. Postal Service to handle an influx of mail-in ballots during the election. “Now they need that money in order to make the post office work so it can take all of these millions and millions of ballots,” Trump said, claiming that those votes would be “fraudulent.”

But COVID-19 has added a fresh urgency for states to reassess the need for in-person voting, as long lines and crowded polling stations are considered risks during a time when health professionals warn of a second wave of infections. (Read about what Dr. Fauci says the U.S. needs to safely reopen.)

How the U.S. uses the mail to vote

In the United States, two voting systems use the mail: absentee ballots, for those who are physically unable to vote in person, and vote by mail, which is open to all voters.

Every state now offers some form of absentee voting, but in some states voters need a valid reason, such as illness or living temporarily outside the state, to request a ballot by mail. Currently, 30 states have adopted “no-excuse absentee balloting,” which allows anyone to request an absentee ballot.

In 2000, Oregon became the first state to switch to fully vote-by-mail elections. Now, four other states—Washington, Colorado, Utah, and Hawaii—offer mail-in voting as an option in addition to in-person voting. California is in the process of joining the club.

In the face of the coronavirus pandemic, voters in every state but Mississippi and Texas were allowed to vote by mail or by absentee ballot in this year’s primaries. Many states plan to do the same for the November general election. But as the election nears, the Trump Administration has ramped up claims that the mail-in system promotes fraudulent voting and favors the Democratic Party. (Read about the tumultuous history of the U.S. Postal Service and its fight to survive.)

The first vote-by-mail uproar

The controversy surrounding mail-in voting has roots back to the Civil War. Before then, only the state of Pennsylvania granted soldiers absentee voting rights. That changed as thousands of men remained deployed far from home in the buildup to the 1864 presidential election. From 1862 to 1865, 20 northern states changed laws requiring in-person voting to allow deployed soldiers to vote. (Read about why the U.S. has never delayed a presidential election—even during the Civil War and 1918 flu.)

The issue quickly became partisan: as Republican candidates supported the cause and appealed to soldiers for their vote, Democrats feared that Republican military leadership would tamper with the results. They complained of Republican interference and accused them of trying to steal the vote and, as a result, were painted as anti-soldier and saw their popularity drop. (The Confederate States voted in its own election.)

Nine state supreme courts heard challenges to these laws, and in grappling with whether remote voting was constitutional or not, four states struck them down.

For proponents of mail-in voting, writes historian David Collins in a thesis about the wartime effort, “it was the legislature’s responsibility, and within the legislature’s constitutional authority, to subordinate the value of election ‘purity’ to the more important wartime imperative of allowing absent soldiers to vote, no matter the far greater risk of fraud.”

Voter fraud and modern controversies

But those risks have been almost nullified in the past century and a half.

By the close of the 1800s, many states had expanded their laws to allow homebound or traveling voters to participate in elections. Today, there are numerous anti-fraud protections built into mail-in balloting, including signature verification, drop boxes in secure locations, and address confirmation.

There is no evidence that mail-in voting increases electoral fraud. A recent Washington Post analysis found 0.0025 percent of votes were deemed possibly fraudulent in the 2016 and 2018 elections. In 20 years and 250 million mail-in votes, there have been only 143 criminal convictions related to fraudulent absentee ballots.

In the 2016 presidential election, 33 million votes—almost one-quarter of the total—were cast by mail. President Trump appointed a commission to investigate voter fraud after claiming that millions illegally voted. It later disbanded without evidence to support his claim.

Trump has claimed that if mail-in voting were adopted nationwide “you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again.” (Trump himself votes by absentee ballot in Florida.)

But a recent Stanford University study examining elections in three states from 1996 to 2018 found no partisan advantage to mail-in voting. “[C]laims that vote-by-mail fundamentally advantages one party over the other appear overblown,” the authors wrote. “In normal times, based on our data at least, vote-by-mail modestly increases participation while not advantaging either party.” (Read about the legacy of a century of women’s suffrage.)

Voting by mail stirred controversy among Americans when Civil War soldiers started filling out ballots from their military stations. But now, according to a recent PEW Research Center poll, more than 70 percent of Americans believe mail-in voting should be accessible to all. Despite recent attacks from the Trump Administration, a bipartisan group of states is moving toward diversifying voting capacity as the coronavirus pandemic puts a freeze on normal life. Experts estimate that the majority of the ballots cast in November’s election will arrive by mail. The question remains whether the infrastructure is ready to count them.

–nationalgeographic.com