Easing tensions

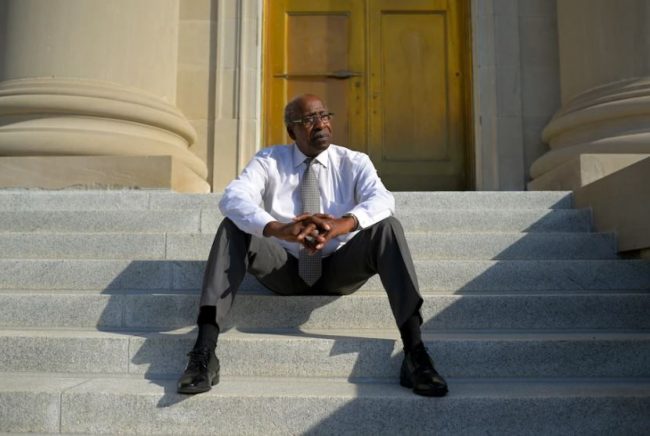

Sherman Saunders lowered himself to a spot on the steps at City Hall on a recent afternoon and remembered the hot day in 1963 when John Lewis came to town.

“This is where I sat,” he said, and began to clap his hands and sing an old protest song. He was only 15 when he watched the civil rights icon stand on the sidewalk below and call for justice.

Danville had been drawing attention since at least 1960, when Blacks staged a sit-in at the Whites-only public library — which happened to be located in Sutherlin Mansion.

By June 1963, boycotts and rallies across Danville culminated in a violent crackdown known as Bloody Monday. Police and deputized residents attacked an evening prayer vigil with clubs and fire hoses, sending 47 injured people to the city’s Black hospital. The event prompted King, who had been in town the month before, to return in July with Lewis and others.

Those memories took new life this year for Saunders, 73, as he saw the nationwide reaction to the killing of George Floyd in police custody in Minneapolis.

“I look at young people marching today, and I look at young people marching 57 years ago,” he said. “We marched for civil rights, for justice — and they’re marching for civil rights and for justice.

The work of that earlier generation has made some things better, he said. The Danville government and police department began to integrate during the 1970s. Saunders, whose mother had been arrested in 1963 for protesting on the mayor’s lawn, became mayor in 2008. He served until 2016, and still sits on the city council.

Crime statistics are improving even as the population declines and unemployment rises. Many give credit to Police Chief Scott Booth, who took the job 2 1/2 years ago after two decades on the Richmond police force, as well as stints with the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security in Charlotte.

Danville gave him a chance to practice long-held ideas about community policing in a small town, Booth said. He has pushed officers to get out of their cars, to walk beats in neighborhoods, to hold conversations in barbershops.

About six months into the job, Booth said he came to realize that Bloody Monday still cast a long shadow over the police among Black residents. So at a public conversation with a prominent Black minister, Booth did something no chief had done before: He apologized.

“I got a lot of positive feedback,” he said. “But I also got a lot of negative feedback. That tells you lot of tension persists.”

Booth continued pushing reconciliation during the demonstrations in June. He was quick to call Floyd’s death a murder — it took the Minneapolis chief nearly a month to do so — and turned out with other officers to support the city’s biggest march.

There, organizer Zydasia Swift, 19, encountered Booth and impulsively gave him a hug in front of more than 100 onlookers.

“A lot of people were wiping their eyes, including me,” Saunders said. “It didn’t happen like that back in the day.”

Swift, who is Black and grew up in the city, credited Booth with easing tensions. “All cops aren’t bad,” she said later. “I have seen tremendous changes in Danville as far as support and people coming together.”

Swift, who graduated from high school this spring, said she never heard about Bloody Monday from her teachers — but she did learn about Danville’s role as the Last Capital of the Confederacy, which is based on Davis taking refuge there for the last eight days of the Civil War.

When she led the protests, Swift said she tried to engage with a group of Confederate defenders who had come out to watch, and said they had a peaceful conversation.

But one of them said later that he wasn’t impressed. “I didn’t think nothing” of the protesters, said Bill Soyars, 73, who is White and retired from “cutting grass and selling cars.” As for Black Lives Matter — “I think all lives matter,” he said one recent weekday, holding a blue Trump flag that he planned to fly at his house.

“The Blacks have taken over city council now, and like the rest of the country, it’s going downhill,” he said.

Transformation

This summer wasn’t the first time Danville has taken a hard look at its identity.

Five years ago, the killing of nine Black churchgoers in South Carolina led towns across the South to reconsider their Confederate flags. Saunders was mayor at the time and urged Danville to confront the flag flying outside Sutherlin Mansion, which is city-owned.

Debate literally drew armies of protesters — one crowd dressed in Confederate uniforms, another in Union blues. City council eventually voted 7 to 2 to ban anything other than U.S., Virginia and POW/MIA flags from city property. In a driving rain, with residents jeering along Main Street, a city police officer cut down the Confederate flag.

The immediate consequence: More Confederate flags went up on private land all over town. A loose-knit group has placed about 15 more battle flags at prominent spots — including at the ends of bridges across the Dan River and atop a 150-foot pole looming over the highway.

City leaders say that if they could figure out a legal way to remove them from private property, they’d do it — because the flags work against Danville’s efforts to market itself to businesses around the country and the world.

“We’ve tried to tell people that economically, it could be a detriment. It does concern us,” said Vice Mayor Gary Miller, who heads a new commission to identify names on streets, schools or anything else that might be racially offensive. Unlike Richmond, Danville has no sculptures of Confederate war heroes; its primary memorials are the mansion and a monument in a cemetery.

“We want to let the world know what our attitudes are about these kinds of issues,” added City Manager Ken Larking. “We’re open for business for all kinds of people.”

Danville has been desperate for jobs since the massive Dan River Mills moved its last textile operations overseas more than a decade ago. Big investments in beautification projects and job-training programs are slowly starting to pay off.

Empty tobacco warehouses are being converted into exposed-brick apartments, breweries and health-food stores. Young people are jogging on riverfront trails.

This summer, Danville was one of 10 places nationwide designated an All-America City by the nonprofit National Civic League — the first time it has won the award recognizing civic engagement and innovation since the 1970s, when the mills were still in full force.

To jump-start its transformation, the city is rolling the dice on a $400 million casino project at the main site of the old mill. If approved by voters this fall, the Caesar’s-backed proposal promises a sleek hotel and entertainment complex on a prominent hilltop, along with 1,300 jobs.

Although some residents think the casino is a step too far, even Confederate holdouts are feeling the pressure to change.

At the foot of the MLK bridge into downtown, the car repair shop that flies a Confederate battle flag on a 60-foot pole is up for sale.

Owner Tom Goddard, 45, had taken the flag down for about two weeks during the June protests — “to make sure we didn’t get outside agitators in here,” he said. While he feels bad that the city is turning away from what he considers to be its heritage, he said it would be futile to fight Danville’s attempt to “brand themselves a different way.”

That future, he said, won’t include him — he hopes to move his shop to the surrounding county to get a little more space.

‘Time to let go’

On a sunny summer day, a train rumbles around the foot of Green Hill Cemetery, briefly drowning out the buzz of cicadas. A ring of cedars surrounds a stone obelisk honoring Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. Small flags mark the graves of Confederate veterans, fluttering like red confetti across the rolling lawns.

At the Federal cemetery on the adjacent hillside lie more than 1,200 Union prisoners who died in Danville’s Civil War jail.

Like the room inside Sutherlin Mansion where the United Daughters of the Confederacy still meets under the terms of a century-old deed, Green Hill Cemetery has been left out of Danville’s reckoning with the past.

The only other Confederate memorials on city property are the small base of the empty flagpole at Sutherlin Mansion and a statue at city hall of Harry Wooding, who served as mayor for 47 years but is also lauded for his stint in the Confederate army as a teenager.

Bennett, the local NAACP chief, wants the flagpole and statue to come down, but said they are not a priority.

“We’ve got a lot of things to work on,” he said, citing the need for affordable housing, accessible health care and getting people to vote in upcoming elections.

Bennett, 64, is also a product of changing times in Danville. His father was the bail bondsman who got the city’s 1960s civil rights protesters out of jail. He remembers going with his grandmother as she voted for the first time and being spat on by White kids outside the polling place.

Bennett said that as a gay man, he might not have been accepted in his leadership position in an earlier era. But to prove how far things have come, he asked a childhood friend to serve as NAACP vice president who is not only White but a supporter of President Trump.

“We all have different opinions and we all still can come together,” Bennett said.

That new era was on exhibit one recent evening when more than 100 people turned out to dedicate a housing project for disabled veterans named in honor of Saunders, a Vietnam veteran.

The city’s first Black treasurer was there, and the first Black woman to head the local community college. Chief Booth and several other officers attended.

Another former mayor — Sam Kushner, who is White — said it was “a fantastic day” for Danville. Not only were they honoring Saunders, but the city council had just approved the framework of a deal for the proposed casino. “There’s so much enthusiasm and civic pride,” he said.

Reminded of Danville’s longtime motto as the Last Capital of the Confederacy, Kushner waved it off.

“I really haven’t heard that in a long time,” he said. “It’s time we let go of it.”

–washingtonpost.com