ECW welcomes back guest author Lucas Simmons.

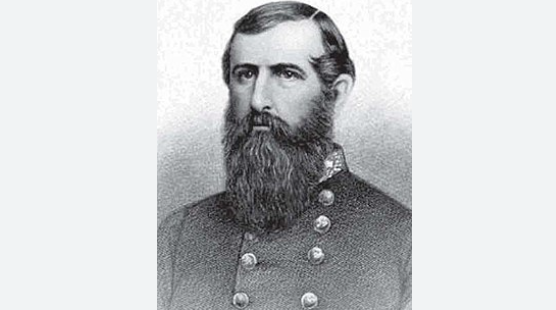

John C. Pemberton ended the Civil War with a less-than-stellar reputation. Confederate surgeon John A. Leavy remarked after the battle of Champion Hill that his commander was either “a traitor or the most incompetent man in the Confederacy.”[1] The truth, at least to me, seems to be somewhere in the middle; he was not a traitor as he is remembered, nor was he the most incompetent general the South fielded. Instead, Pemberton was in over his head and stuck in a difficult situation.

The truth about Pemberton is that he was advanced to a rank that was beyond his capabilities too quickly. Historian James Arnold argued that this was because Pemberton possessed the theoretical knowledge required for coastal defense and army command.[2] One only needs to glance at his promotion history in 1861 and 1862 to see the problem. He resigned from the United States Army with the rank of captain and brevet rank of major in the artillery. Upon his departure, he was commissioned a lieutenant colonel in the Confederate Army.

Just ten days later he was promoted again to colonel.[3] Around the same time, he was also promoted to lieutenant colonel of artillery in the Provisional Army of Virginia.[4] Upon Virginia’s official entry into the Confederate States of America, Pemberton reverted to his United States Army rank of major in the artillery, for two whole days, before being promoted to brigadier general. In December 1861, he was promoted to major general and given command of the important port of Charleston, South Carolina. Pemberton rose from captain to department commander without seeing the battlefield at any of the ranks he breezed over. To put this into context, this meant a man who only months prior had been commanding a few hundred men and a handful of artillery pieces was now commanding one of the Confederacy’s most crucial ports.

Pemberton’s command of the department proved short-lived. A combination of his personality and his lackluster performance against a Union offensive left the city elites unimpressed. Pemberton responded to a Union naval attack by suggesting to Governor Francis Pickens that he would abandon the key forts in Charleston Harbor, and even the city itself, if it meant the preservation of the garrison.[5] Only orders from Robert E. Lee to hold the city prevented a disaster.[6] Even the repulse of a Union attack at Port Royal could not restore him to Governor Pickens’ favor.[7] Their issues ultimately boiled down to, at least in the mind of some in Richmond, that Pickens did not approve of a Northerner being in command.[8] Pemberton himself assumed that the issue came down to Pickens and the Fire-eaters preferring that P.G.T. Beauregard, the hero of Fort Sumter, command the city’s defense.[9]

Here we arrive at perhaps Pemberton’s most confusing promotion. Rather than ship him back to the artillery or a less important field command, Jefferson Davis decided that the theoretical understanding that Pemberton displayed early in the war qualified him for command of the Mississippi River fortresses of Vicksburg and Port Hudson. His promotion to lieutenant general ensured that he outranked his cavalry commander, Earl Van Dorn, and had seniority over his division commanders, who otherwise held date of rank on him. Upon his arrival, Pemberton did not make a good first impression. Confederate Sgt. Edwin Fay remarked that the new commander “cannot contain the common sense of a regimental commander, much less that of a corps.”[10]

Whatever ill feelings his men had toward him were quickly alleviated as Pemberton set out to restore the morale that had been crushed at Shiloh, Corinth, and Iuka. Combined with improvements to Vicksburg’s defensive perimeter, the drilling and relationship-building soon bore fruit for the Confederacy. Barely six weeks after arriving in Mississippi, Pemberton’s army handed Union general Ulysses S. Grant two stiff defeats. Van Dorn’s cavalry smashed Grant’s supply lines in northern Mississippi, ending the land attack. During this same period, the Vicksburg garrison repulsed a second attack by William T. Sherman at Chickasaw Bayou.

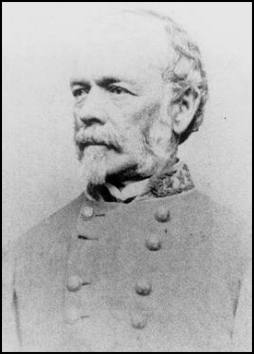

While Pemberton was certainly out of his element despite his victories at Holly Springs and Chickasaw Bayou, the command hierarchy that Davis established in the Western Theater did the Pennsylvanian no favors. Davis appointed Joseph Johnston commander of all Confederate forces between the Appalachians and the Mississippi River. This added a second layer of complexity to the equation; both of his bosses had conflicting ideas on how to defend the city. Davis thought that the Vicksburg and Port Hudson garrisons should hold while Johnston marched to their aid.[11] Johnston thought that his only hope for stopping Grant was to bring part of Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee and Pemberton’s Army of Mississippi together to face Grant.[12]

By the time Pemberton set out with his army to either confront Grant or link up with Johnston, he had already made the fatal error of the campaign. The aftermath of the battle of Port Gibson presented a chance to disrupt or delay Grant’s campaign. Rather than seize an opportunity to attack the exposed flank of James McPherson’s XVII Corps, Pemberton hesitated. In a moment where aggressive action could have stalled Grant’s army yet again, Pemberton deferred to his senior division commander, William Loring, about how to proceed.[13] Loring, aware that the terrain favored the defender and weary of the rapid Federal movements, decided an attack was unfeasible.[14] Pemberton’s time at Charleston meant that he never stopped fearing a naval attack on the city, to the point that he weakened his field force to augment the garrison when he finally confronted Grant outside of the Vicksburg perimeter. These concerns possessed a small amount of merit; David D. Porter had twice run the guns at Vicksburg and largely avoided damage from the batteries on Haynes Bluff. Taking such a risk went against his orders from Davis to avoid unnecessary risk to the city.[15]

Davis ordered Pemberton to hold Vicksburg and Port Hudson at all hazards. Meanwhile, Johnston ordered him to bring his army to Jackson to prepare for the counteroffensive against Grant. Instead of asking for clarification or weighing the odds both possessed, Pemberton decided to please both of his bosses. He took the divisions of Carter Stevenson, William Loring, and John Bowen with him and left those of John Forney and Martin Luther Smith to defend the city. This decision came back to haunt Pemberton at Champion Hill. The decisive battle of the Vicksburg Campaign was a classic “last side to attack wins the day” type of battle. Bowen’s division came close to smashing the Union line, but was driven off by a lack of reserves and supporting units. Had they not been left behind, Smith and Forney’s divisions could have altered the outcome of the campaign.[16]

The decision to settle in to await relief saw Pemberton make a final catastrophic mistake. He abandoned Haynes Bluff, the key artillery platform that had made the navy’s life so difficult for much of the year, and Johnston had told him Vicksburg was worthless if lost.[17] In a bid to shorten his lines, Pemberton turned the key to the position into the key to his defeat.

His insecurities after Charleston led him to hold out until his men and supplies were exhausted. However, the reality was his fate was sealed before Champion Hill. Vicksburg’s only hope was for another disruption to Grant or the proposed merger of Confederate forces to confront Grant in tandem. The combination of the attack that never was against XVII Corps after Port Gibson and the failure to link up with Johnston meant that it was only a matter of time before the city fell.

Advanced through the ranks at a record pace, Pemberton likely started the war if not in the rank he was best suited for, then perhaps the role he was best suited for, that of an artillerist and advisor. His successes against Grant came in small unit, regimental, and brigade-sized. The siege of Vicksburg showed Dr. Leavy wrong in his assertion that his commander was a traitor, but it showed Sgt. Fay correct; Pemberton, a good artillerist and passable theorist, was indeed incapable of grasping the nuances of corps command.

Lucas Simmons holds a B.A. in history from Southern Virginia University and an M.A. in history education from Grand Canyon University. He enjoys learning about the Civil War, especially the Valley and Overland Campaigns. When he is not glued to a book or writing project he enjoys swimming, hiking, and giving tours of his native Shenandoah Valley.

—

Endnotes:

[1]. “Extra Voices: Bad Officers,” The Civil War Monitor, June 2017, https://www.civilwarmonitor.com/extra-voices-bad-officers/.

[2]. James Arnold, Grant Wins the War: Decision at Vicksburg (New York: Wiley & Son, 1997):26.

[3]. John H. Eicher and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001):423.

[4]. During much of May, Virginia had yet to vote on the ordinance of secession and had its own army. It was not uncommon for a Virginian to hold one rank in the Provisional Army of Virginia and another in the Confederate Army. Following Virginia’s secession, the Commonwealth’s forces would be absorbed into the Confederate Army, and all personnel would permanently assume their Confederate rank.

[5]. Arnold, Grant Wins the War, 25; John C. Pemberton, Pemberton: Defender of Vicksburg (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1942):28.

[6]. Pemberton, Pemberton: Defender of Vicksburg, 31.

[7]. Pemberton, Pemberton: Defender of Vicksburg, 25-28

[8]. Pemberton, Pemberton: Defender of Vicksburg, 34-35; Pemberton includes excerpts of letters from George Randolph that he received during his time in Charleston. The general’s birth in Philadelphia was a favorite topic of the governor, according to Randolph.

[9]. Pemberton, Pemberton: Defender of Vicksburg, 26-28; The excerpt from Randolph on p.34 reinforces this notion; Arnold, Grant Wins the War, 28-30.

[10]. Bell Irving Wiley, ed., “This Infernal War”: The Confederate Letters of Sgt. Edwin H. Fay (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1948):179.

[11]. Arnold, Grant Wins the War, 124-125.

[12]. Joseph E. Johnston, Narrative of Military Operations (New York: Appleton & Co, 1874):152-153; Excerpts of Johnston’s letters to Davis outlining plans and concerns for the Western Theater can also be found on p.495-497.

[13]. Arnold, Grant Wins the War, 120.

[14]. Arnold, Grant Wins the War, 120.

[15]. Arnold. Grant Wins the War, 124-125.

[16]. Arnold, Grant Wins the War, 228.

[17]. Arnold, Grant Wins the War, 234.

–emergingcivilwar.com