SOUTH CAROLINA: Misconceptions of a Civil War general’s time in Columbia persist, historians say

COLUMBIA — Many who grew up in South Carolina have a very particular picture of Gen. William Sherman’s March through the state. One shaped by historical accounts passed down for generations and fiery images from “Gone With the Wind.”

In Columbia, the memory of Sherman burning the city to the ground in the closing days of the war remains ingrained in the city’s bones. This is despite of the fact that the general is likely not responsible, according to modern historians.

That misconception is one of several that continue to haunt the collective memory of Sherman’s March, the war and its aftermath in Columbia, South Carolina and the South as a whole, some local historians say.

A hasty retreat and cotton in the streets

When Sherman’s troops entered Columbia on Feb. 17, 1865, the city was one of the most prominent remaining targets in the South, said Melissa DeVelvis, a historian of the U.S. South and Assistant Professor of History at Augusta University in Augusta, GA.

Columbia was one of the largest surviving railroad and industrial hubs not yet taken by Union soldiers, with many military targets and supplies shipped in from Charleston for safe keeping, she said. It also held political significance as the capital of the first state to secede.

The city had been hastily abandoned by Confederate forces in advance of Sherman’s approach.

One of the last orders given was to move cotton bales out of warehouses and into the streets to be burned before they could be taken along with the city. The order was rescinded at the last minute, but it’s unclear how many of the troops got the word before they set fire to any bales and fled, DeVelvis said.

“It was just a big cluster of the Confederacy getting out of town,” she said. “So when you think about memory, they remember the burning and not so much the uncoordinated retreat.”

The record shows Sherman ordered railroad and military facilities and some homes of prominent Confederate leaders in the city burned, but not the wholesale torching of the city, she said.

But extremely high winds, the cotton bales in the streets and copious amounts of alcohol in the city allowed the fires to spread.

The fire was complemented by looting by some locals and soldiers, while other troops tried to fight the blazes.

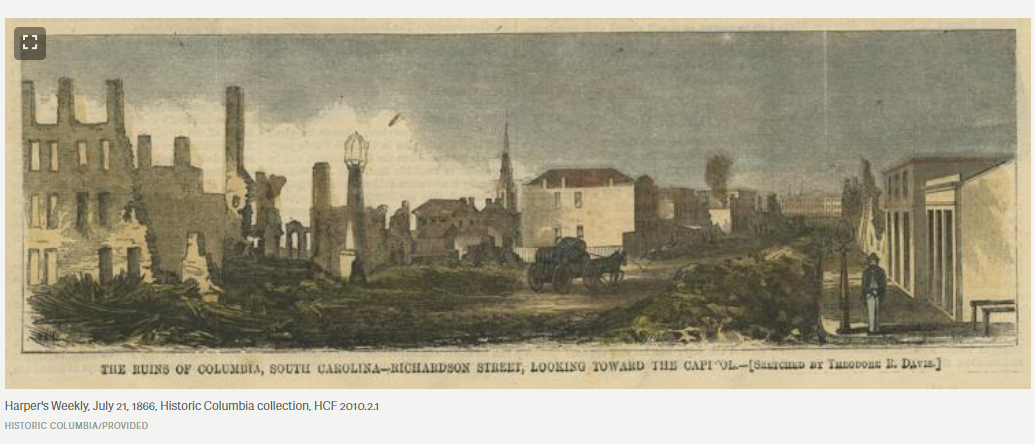

One of the biggest misconceptions about Sherman’s time in Columbia is that the entire city burned that night, said John Sherrer, the director of Preservation at Historic Columbia.

While most of what is now Main Street, buildings in what is now the Vista and the then-incomplete Statehouse did burn, the damage constituted about one third of the city, rather than its entirety, Sherrer said.

Many notable buildings, including those on the University of South Carolina’s Horseshoe and the First Baptist Church where the delegates first met to declare the state’s secession in 1860, survived the fire and still stand today.

Though the idea that all of pre-1865 Columbia was lost that February is still prevalent, more historic structures were lost to urban renewal projects in the 20th Century than were in the fires, he said.

“I was born and raised in Columbia, South Carolina,” he said. “And I’ve always heard, everybody always says, ‘Oh, if it weren’t for Sherman, Columbia would have all this history. You know, there’s nothing left in Columbia. There’s no history of Columbia because Sherman destroyed it all.’ And that’s just not true.’”

Sherman and the Lost Cause

Some of the confusion as to who or what was responsible for the burning of Columbia and Sherman’s legacy in the South comes down to unreliability of firsthand accounts written in the chaos of war and the bitterness of defeat and occupation, Sherrer said.

“If you think about it, in the post Civil War period, particularly during Reconstruction, when former white leaders who had arguably lost the most monetarily through emancipation of formerly enslaved workers, who had lost a great deal of capital and physical standing, they needed to create a narrative that was easily followed — something that created a hero and a villain,” he said.

Sherman’s March feeds into the broader “Lost Cause mentality” — a longstanding belief across the South that glorifies the Confederacy and downplays the severity of slavery — that began to emerge almost immediately after the war and lasts to the present day, DeVelvis said.

“It starts as a way to mourn their dead, but then it becomes, ‘Actually, because what they fought for was righteous, and they weren’t defeated but merely overwhelmed,’ and then you add in ‘Well if their cause was righteous, then slavery must have actually been a benevolent system where enslaved people were happy,’” she said.

Misconceptions about Sherman’s March, including the wholesale burning of a surrendered Columbia, were passed down through oral retellings and public school curriculum in the South for decades. The historic record didn’t begin to be corrected until after the Civil Rights movement a century later, she said.

“The Confederacy loves to talk about their honor in war, and so they use Sherman as an example of being dishonorable in war,” she said. “And of course, a dramatic burning of a city is a perfect stage for that. And that’s why, to this day, people hate Sherman.”

–postandcourier.com