The families worked with archaeologists and volunteers to sift through soil that had been scooped from the floor of a cabin on the Sotterley Plantation.

Now, Bankins occupied that same space — and she wasn’t alone.

A few feet from her in the cabin, stood John Briscoe Jr., 64, whose great-great-grandfather had owned Sotterley — and the enslaved people who worked and lived on the grounds — for years.

The two had come together that day to help a team of archaeologists from St. Mary’s College of Maryland and volunteers carefully dig and sift through buckets of soil that had been scooped from a two-foot-deep hole in the cabin’s dirt floor. They hoped to find bits of artifacts that would offer clues about what life had been like for those who lived there and shed light on the region’s history.

“This is a shared experience,” Bankins said. “We are both here because our ancestors survived. We have to learn it and share it.

“This site has survived,” she said. “It was a site of American history, of resilience and pain.”

Their work to examine Sotterley’s history comes at a time when the Trump administration has said the Smithsonian Institution has “come under the influence of a divisive, race-centered ideology.” Trump has said in recent weeks that the Smithsonian is “out of control” and focuses too much on “how bad Slavery was,” advising his administration to do a review of its content.

At Sotterley, Briscoe said he became involved with the dig because he wanted to learn more about the property and its history.

“We’re not trying to whitewash what happened here,” he said. “We don’t try to sweep it under the rug. It was an unfortunate period of time in our history.” But he and Bankins, he said, “have an understanding that we, in our generation, don’t have control over what happened then.”

“All we can do is discuss how it was and how we can make things better,” he said, “and preserve what once was.”

Over about five weeks at the site, the group discovered about 2,500 pieces of artifacts in the cabin. Several hundred of the items were found under the dirt floor of the cabin, an indication, historians said, that the people who lived there probably made pits that served as lockers to store food and hide precious items. They found slate pencils, scraps of newspapers, a partial stem of a tobacco pipe, bones of a possum, teeth, several small glass medicine bottles, a hook-and-eye closure for sewing and a piece for a game made from mother-of-pearl.

“There was life here,” Bankins said. “It makes me think there was a woman sewing here, or maybe a mother teaching her children to read and write or kids playing a game. You find small things and think, ‘Did it come from the Briscoes’ relatives or mine?’ Maybe they brought it down here when it was going to be trashed or thrown out.”

For Bankins, a retired supervisor at an electric company, bringing her mother — Elizabeth “Betty” Bankins, 83 — to the cabin to help in the archaeology work a few times has been especially poignant. When Garrett Ternent, one of the archaeologists, found a broken piece of a wall in the cabin, he brought it over to show Bankins’ mother.

At first, she became quiet and took a seat to rub the piece in her hands, her daughter recalled. The elder Bankins had grown up not knowing much about her family’s life of slavery at Sotterley.

“I knew of the place,” she said, “but slavery was just something that wasn’t talked about much back then.” She had learned more of her family’s history at Sotterley from genealogy research her cousin had done. Kane, she had learned, was a skilled plasterer who was often sent by his enslaver to work on other large homes in the area.

“To hold part of a wall,” the elder Bankins said, “that was part of somebody’s house who lived before you. Who was part of your family. … It was powerful.”

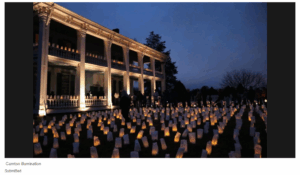

Built in 1703, the once-grand Sotterley plantation overlooked the Patuxent River in the small town that’s now called Hollywood. Its location gave its owners access to the shipping lanes of the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean, said Katherine Humphries, the interpretive programs manager at Sotterley. The plantation owners grew and exported tobacco, Humphries said, and it became one of the ports on the Atlantic coast where enslaved people first made it to land, making it a site in the transatlantic “Middle Passage” of the enslaved person trade.

In 1720, a ship named the Generous Jenny brought roughly 200 enslaved people to Sotterley for the estate’s then-owner James Bowles, who was an agent for the Royal African Company — a slave-trading company, according to records Humphries reviewed from the National Archives in the United Kingdom. At least 29 captive people died during the voyage.

Briscoe’s family came to Sotterley in 1826 after Walter Hanson Stone Briscoe married Emeline Dallum, the stepdaughter of Sotterley’s then-owner. The couple later inherited the manor house and its 400 acres.

In 1849, the Briscoes’ and the Bankins’ families intersected at Sotterley when Kane — Bankins’ enslaved relative — came to live there.

Born into slavery in 1818, Kane’s parents were enslaved by different families, so he lived with his mother. When she was sold, Kane was sent to another enslaver to settle a debt, according to historians. He was 9 years old.

At 29, he married an enslaved woman named Mariah, and they had seven children. But his family was separated when the plantation owner died in 1848 and the owner’s will dictated that Kane’s family be divided among his children. Kane was sold to Colonel Chapman Billingsley and his wife and children to Walter Hanson Stone Briscoe.

Because the two men’s estates were close, Kane was allowed to live with his family at Sotterley. His wife, Mariah, died shortly after he got to Sotterley, and he married another enslaved woman, Alice Elisa Bond. His descendants said between his two marriages, Kane had 18 children, many of whom were born in the cabin, which measures about 16 feet by 18 feet.

When he was with his family, Kane — according to his descendants — made furniture and musical instruments, including a banjo that he played. He was also considered the “doctor” of those who were enslaved at Sotterley because he knew how to use medicinal herbs from the nearby creek and woods.

After the end of slavery in Maryland in 1864, Kane stayed at Sotterley and worked as a tenant farmer until 1879 when he moved about eight miles away to his own home. He died at the age of 71 in 1889.

The Briscoes sold the Sotterley estate in 1910 to Herbert Livingston Satterlee, and his daughter, Mabel Satterlee Ingalls, later came to own the property, according to Humphries. She established a foundation in 1961 to run the property and opened the house and grounds for guided tours.

In the 1970s, Bankins’ cousin — Agnes Callum, a retired postal worker who lived in Baltimore — started researching her family’s genealogy. Callum used to take busloads of her relatives to Sotterley so they could see where their relatives were enslaved.

She eventually contacted Briscoe’s father, John Hanson Briscoe, a former speaker of the Maryland House of Delegates and a St. Mary’s County Circuit Court judge.

When Callum met the elder Briscoe, their families said, she shared with him a copy of an inventory she had made over decades that showed the names of enslaved people owned by different families, complete with ages, sex, their skills and sometimes the price paid for them.

The elder Briscoe and Callum eventually ended up serving together on the board of trustees for the nonprofit, Historic Sotterley, that now runs the site, and in the 1990s they helped to raise funds to restore the manor house and cabin, both of which had deteriorated.

In 2000, Sotterley was designated as a National Historic Landmark and the restored cabin was dedicated in honor of Callum in 2017. The elder Briscoe died in 2014 and Callum died a year later. The UNESCO Site of Memory for the Routes of Enslaved Peoples named Sotterley in 2019 as a Middle Passage arrival site in the U.S.

Bankins and John Briscoe have followed their relatives’ footsteps and volunteered at Sotterley. Briscoe serves on a committee that helps to keep up the property’s buildings and grounds, and his sister is vice president of the board of trustees. And this year, Bankins was chosen as the board’s president, making her the first African American woman to serve in that role and the first descendant of someone who was enslaved at the property.

They both — like their relatives — recognize their connection of being descendants of enslaved people and their enslavers, but don’t dwell on it. Bankins asked aloud one afternoon as some of her relatives and Briscoe rested under a tree from working in the cabin, “Does he owe me an apology for slavery?”

“Hell no,” she said. “You can’t change history.”

For her, Briscoe’s showing up and helping with the archaeological dig was “overwhelming.”

“To know he wanted to learn,” she said, “and that he wanted to help discover the past, that meant a lot.”

–washingtonpost.com