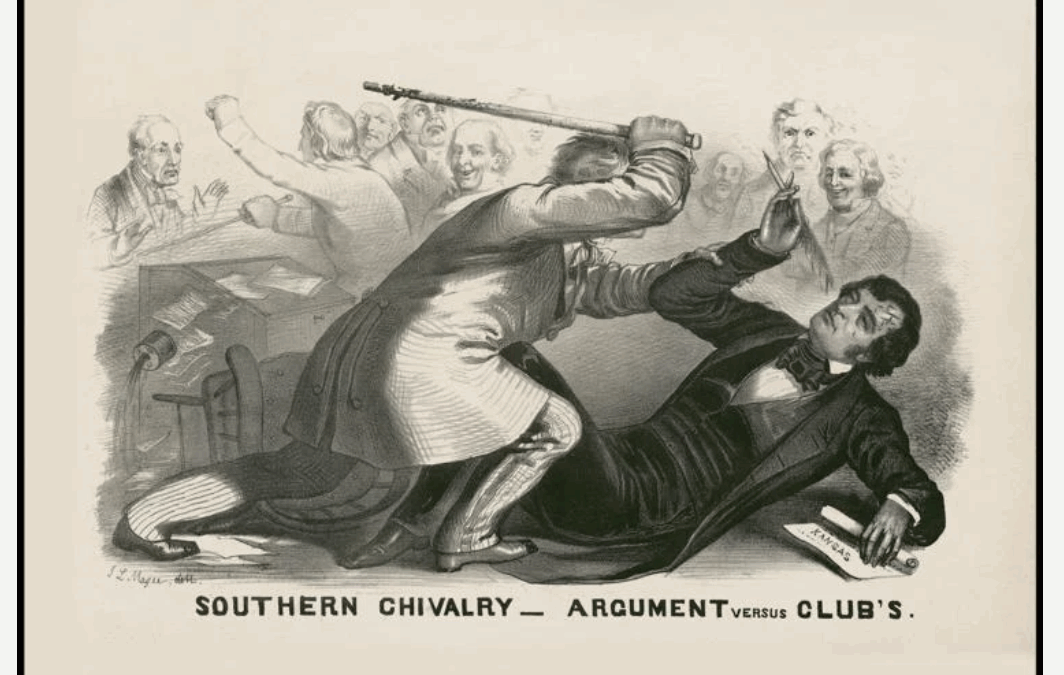

Nearly 170 years after South Carolina congressman Preston Brooks raised his cane and beat abolitionist Charles Sumner bloody on the Senate floor, the pro-slavery lawmaker behind one of America’s most notorious acts of political violence is getting a full-length biography.

Historian Paul Quigley widens the lens in his new examination, “The Man Behind the Cane: Preston Brooks, Political Violence, and the Road to the Civil War,” which focuses on both the caning and the larger forces that shaped Brooks.

The deeper Quigley dug into Brooks and the role he played in a nation on the brink of war, the more his findings felt uncomfortably timely, he said.

“With the caning, it widened the divide between North and South and made people more amenable to the idea that maybe violence in politics is OK,” Quigley said. “That’s the danger today as well, where things escalate and violence begets further violence.”

He added, “A lot of that depends on how people respond: whether they cheer perpetrators on, or if they unequivocally denounce violence from any side.”

The book’s introduction makes the connection even more explicit between the 1850s and today. In it, Quigley writes: “It is especially vital to learn about Preston Brooks when there are so many potential present-day Preston Brookses around us: angry, alienated men, who explain away their failures with claims that they and their kind are unjustly disadvantaged in a rapidly changing world.”

“They, too, might see some spectacular act of public violence as the best means of expressing their discontent, soothing their inner demons, and challenging politics as usual,” it continued. “The way we talk about violence, the way we fight over words — these things matter as much today as they did when Preston Brooks walked into the Senate chamber and raised his cane.”

The book revisits how the country slid into civil war and how 60 seconds of violence on the Senate floor changed its path. In 1856, Brooks attacked Sumner in retaliation for an anti-slavery speech that insulted his family by brutally striking him repeatedly as other senators struggled to intervene.

Brooks, a pro-slavery Democrat, became a hero across the South after the attack, while in the North the caning sparked outrage, mobilized voters and turbocharged the rise of the newly formed Republican Party.

He also got a nickname — “Bully Brooks” — but struggled with how he was vilified in Northern newspapers.

Sumner’s speech singled out two pro-slavery senators, including U.S. Sen. Andrew Butler of South Carolina, who had recently suffered a stroke.

Sumner mocked Butler’s lingering effects from the stroke and accused him of having taken “the harlot slavery” as his mistress— an affront that Brooks viewed as a direct challenge to his family’s honor and to Southern notions of manhood.

Brooks was related to Butler, and the words cut deep. To do nothing, Quigley said, was simply not an option for a man trying to maintain his standing in a culture where honor was paramount.

“Brooks felt so much pressure in the two days between the speech and the caning,” said Quigley, an associate professor at Virginia Tech and director of the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies. “He pretty much knew that he had to do something in order to avoid being accused of being a coward.

“And violence was typically the result, or the tool, that people used in these kinds of situations,” he later added.

To understand Brooks more fully, Quigley traveled to Edgefield to get a sense of the place and landscape that shaped him, even more than a century after Brooks’ time. He went kayaking on the Savannah River in search of an island where Brooks fought a duel, only to discover that a power dam built in the 1970s likely submerged it. He also tracked down a descendant, reviewed excerpts of Brooks’ personal diary and traveled to the site of Brooks’ childhood home.

“I really wanted to do everything I could to walk in his footsteps and just see the places where his character was formed,” Quigley said.

After the caning, a majority of House members voted to expel Brooks, but the effort fell short of the two-thirds required. Brooks resigned anyway, saying voters should decide his fate.

They did, and he was unanimously reelected back to the vacated position.

That dynamic — how the public responds to political violence — is what interests scholars today as such acts are seemingly becoming normalized. The book’s pending publication comes at a time when America is once again deeply polarized and grappling with an uptick in political violence, including the recent public murder of conservative activist Charlie Kirk, the political assassination of Minnesota House Speaker Melissa Hortman and repeated assassination attempts on Donald Trump while he was running for president in 2024.

In the most recent Winthrop University Poll of state attitudes, nearly half of South Carolinians (48 percent) said they strongly or somewhat agree with the statement: “Our American way of life is disappearing so fast that we may have to use force to save it.”

Poll director Scott Huffmon said it’s an attitude that has risen in popularity in recent years.

“The number of people who think force or violence might be necessary to ‘save our country’ or the ‘American way of life’ is both astounding and disturbing,” he said. “When people become convinced that the other side hates them, can’t be trusted and will destroy what they value, some start to believe that force may be necessary.”

The book, published by Oxford University Press, is due out in May.