The ghost of Nathan Bedford Forrest haunts the South, but not in the way you might think.

This is no Halloween tale, but the lasting legacy of a Confederate general who became the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. Admired by some (who tout his military prowess and “up from the bootstraps” success during the Civil War) and reviled by others (who decry his brutal racism and years as a slave trader), Forrest remains a polarizing figure in American history.

Monuments to Forrest can be found throughout the South, including statues, busts, historical markers and buildings that bear his name. Some have been removed or relocated in recent years, and they’re part of a larger conversation about the validity and future of Confederate monuments in the United States

Amid social unrest that has rocked the country in 2020, and an upsurge in the Black Lives Matter movement, a new book has emerged that grapples with the issue of Confederate monuments — specifically, those paying tribute to Forrest — and their resonance in American life.

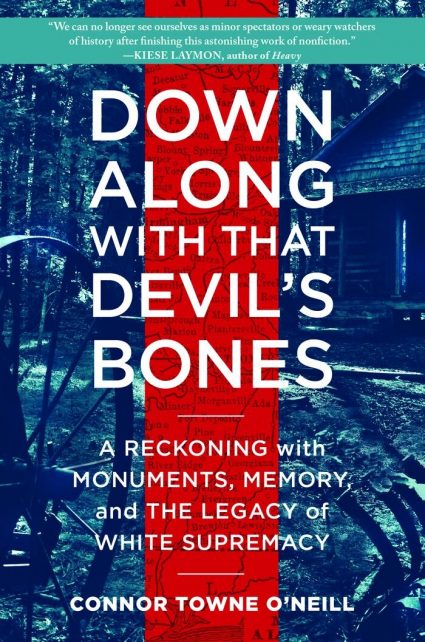

“Down Along with That Devil’s Bones: A Reckoning with Monuments, Memory and the Legacy of White Supremacy,” was written by Connor Towne O’Neill, an instructor in the English department at Auburn University. O’Neill, 31, a Tuscaloosa resident, earned a master’s degree from the University of Alabama in 2017. He’s originally from Pennsylvania, and has been teaching at Auburn for three years.

“For the last five years, I’ve chased Forrest’s memory across the country,” O’Neil writes, “standing in the shadows of his monuments, talking with the activists fighting to take them down and the admirers working to keep them up, investigating the stories these monuments tell and searching out the ones they withhold — stories of cavalry raids and cemetery standoffs, white supremacist movements and nightmarish sculptures, impassioned campus protests and backroom political intrigue, all amounting to a reckoning of America’s past and a desperate struggle for its future.”

“Down Along with That Devil’s Bones,” published on Sept. 29 by Algonquin Books, is O’Neill’s first book. He’s written articles for New York magazine, Vulture, Slate and the Village Voice. O’Neill also worked as a producer on NPR’s 2019 podcast “White Lies,” which explores a 1965 murder in Selma.

In an email interview with AL.com, O’Neill discussed the impetus for “Down Along with That Devil’s Bones” and detailed his thoughts on the legacy of Forrest and the controversies over Confederate monuments.

Q: Why did you want to write this book?

A: I found that debates about Confederate monuments revealed a deeper set of questions about race, power and memory in America. Monuments are double-jointed, holding the past in the present, the present in the past. And when activists campaign to take down a monument, they aren’t just challenging the legacy of a figure from the past, they’re taking on the longstanding powers that have kept the statue up. So covering these campaigns were a way of documenting power struggles over race and equity in the present while also situating them in the deeper historical moments reflected in the monuments.

Q: There are lots of Confederate monuments in the South, devoted to different people. Why did you pick Nathan Bedford Forrest as the dominant figure in your book?

A: I’m not sure that I picked the topic so much as I fell down a rabbit hole about it. That’s all because of a chance encounter I had back in the spring of 2015. It was the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday — the attack by Alabama police officers on nonviolent civil rights demonstrators at the foot of Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge. I was there to report on the anniversary and to hear President Obama’s speech. Some 40,000 other people showed up, too. So, on a hunt for free parking, I pulled into the cemetery that’s just a few blocks from downtown. It was there, in the cemetery’s Confederate Memorial Circle, that I met the “Friends of Forrest.” They’re a neo-Confederate group who, I learned, had spent the better part of the last two decades fighting about a statue of Forrest they’d put up.

The dissonance of that encounter — Neo-Confederates on a major civil rights anniversary?!? — sent me down a rabbit hole of Forrest’s life and symbolic afterlife, asking questions about who Forrest was and what it meant to put up a statue of him in 2015. And he proved to be a revealing figure. A slave trader; an accused war criminal; the most-promoted soldier of the Civil War, Union or Confederate; a man who, according to Shelby Foote, was one of the two geniuses to emerge from the war (the other being Lincoln); and a man who, after the war, would go on to serve as the first Grand Wizard of the Klan. So his life touches on crucial issues from the Civil War era. And there are so many monuments of him that connect his life to places and moments in time long after the war’s end.

There’s the equestrian statue of Forrest that goes up in 1905, just as the City of Memphis was imposing Jim Crow laws and in the aftermath of Ida B. Wells’s investigative reporting on lynchings. There’s the building named after Forrest on campus at Middle Tennessee State University, christened four years after the Brown vs. Board of Education ruling and four years before the school would comply with that integration order. Then, of course, the statue in Selma, dedicated just after the town elects its first black mayor and then, after it was stolen, rededicated just weeks before the Charleston Nine murders. So, all to say, Forrest’s life and legacy offer revealing entry points into crucial moments, past and present.

Q: What makes Forrest stand out as such a key figure in Southern history or Southern consciousness, perhaps more so than Robert E. Lee or Jefferson Davis?

A: Unlike Lee and Davis, Forrest didn’t go to West Point; he hardly went to school at all. He is seen as a more “instinctive” military leader and thus has an “everyman” appeal. There’s a harder edge to Forrest’s memory, too. He was brash and uncouth, not the embodiment of the “Southern gentleman” that some people like to see in Lee. And because Forrest enlisted in the war as a private and fought mostly in the overlooked Western theater of the war, there’s a sense that if only Forrest had been given a more prominent position, well, then the South might have won. A good deal of teeth gnashing and sabre rattling gets channeled into Forrest’s mythos. He is the Confederate counterfactual, the great hope of the Monday morning Rebel quarterback who refuses to accept the war’s end or outcome.

Q: Four monuments to Forrest — in Selma, Murfreesboro, Nashville and Memphis — provide an organizing principle for your book. Why these particular monuments? Does each symbolize a specific issue you wanted to highlight?

A: The fight over the Forrest statue in Selma precipitated a lot of the debates that we’ve had in this country in recent years over the meaning of monuments, so the Selma section serves as a prelude. It underscores that the battles over monuments are about the present as much as the past. In Murfreesboro, the fight over Forrest Hall on the campus of Middle Tennessee State University brought up issues of racial equity on campus. That school year, protests were breaking out across the country from Northern Ivies to Southern state schools and the protests on campus at MTSU served as a microcosm for that broader campus mobilization. The debate also pointed up the deeply polarized nature of political debate in America in 2016.

In Nashville, the Forrest statue on the shoulder of I-65 was sculpted by a man who organized the statewide resistance to school integration in Tennessee in the 1950s, who represented James Earl Ray in the 1970s, and, who in the 1990s, co-founded the League of the South, a group who instigated violence in Charlottesville in 2017. So the story of the statue and its artist allowed me to draw a straight line through much of the 20th century and the battles waged to maintain white supremacy. The statue in Memphis serves as the climax of the book — the story of the statue’s dramatic removal and the ways that different groups in the city responded offered a portrait of a community struggling to come to grips with the weight of its history.

Q: Were you tempted to add more monuments and more chapters to the book?

A: Yes, absolutely. I wanted to write about at least ten of them, but I came to see how that approach would spread the book too thin. It would be superficial, more spectacle than substance. Instead, by narrowing the scope to four meant I could write into each of these monuments in a deeper way. And it allowed the space to use each monument as a prism for looking at all the moments through time that they touch on, from early colonial days up through the present. It was important to me to try to capture the sweeping history of Forrest in each city.

Q: You encountered that first monument to Forrest in Selma five years ago. What’s it been like with Forrest living in your head since 2015?

A: It’s been a doozy. Wrestling with Forrest has led to lots of discomfiting realizations about how psychotic America’s notions of race are and how they’ve been implemented to benefit folks who look like me. So while it hasn’t been pleasant, it has been instructive. Strange as it sounds, Forrest has been, for me, a useful teacher of American history.

Q: As your book makes clear, Forrest has admirers and detractors, and they are highly polarized. Can you summarize the basic argument for or against him used by each group?

A: There’s the “Big Three” against Forrest: Slave trader, the Butcher of Fort Pillow and the Grand Wizard of the Klan. I’d add that his role operating a convict leasing plantation — a system known as “Slavery by another name” — is an underemphasized reason to abhor the man. The folks who admire him cite his military instinct. He’s “the legendary solider of Tennessee” as one person put it to me. And he has that “everyman” appeal — no high falutin education, not from a prominent family, etc.. And it worth saying that, even though they don’t write it in marble on the base of the monument, the reasons he’s loathed by some are also the reasons he’s loved by others.

Q: Are we still fighting the Civil War in the South?

A: I think the country is still fighting about what the outcome, and thus the consequence, of the Civil War should be. American society is still structured along lines meant to hoard wealth, opportunity and access for white Americans. We can see that in everything from the racial wealth gap to the disparate deaths from COVID-19 to voter disenfranchisement efforts. To my mind, the central question of the Civil War was whether a slave society could transform itself into a multi-racial democracy. We haven’t yet. Not fully. So we’re still fighting about the meaning of the war.

Q: In your book, a you talk about a “Cold Civil War.” Can you explain that concept?

As the leaders of the Confederacy and the various Articles of Secession make clear, the war was fought explicitly to maintain slavery as an institution and expand it into further into the west. And they were justifying that system by telling the threadbare lies of black inferiority and white supremacy. And while war led to the emancipation of those enslaved, it didn’t uproot that underlying ideology. The “Cold Civil War” refers to all the proxy wars fought in the years since, in which the battlefields were courtrooms, classrooms, bank offices and congressional chambers, but the aim was still the same: to keep the country running along lines meant to provide wealth, resources and opportunity to white Americans.

Q: A recurring phrase in your book is “Same war, same general.” Tell us about that.

A: The phrase comes from a conversation I had with James Perkins Jr., the former mayor of Selma, Alabama. Just a few days after he was inaugurated, a statue of Forrest went up on city property. “That statue,” he told me, “was a pronouncement of war.” The fight over the Forrest statue, he told me, was “a continuation of a battle that started way back in the 1800s. And they had the same general.” It’s a fight over who gets remembered, who holds power, whose lives matter, and I found it playing out in every city I reported on, so I used the phrase as a refrain.

Q: If people remember one thing about your book after reading it, what would you like that to be?

A: Monuments encourage a naive view of history. They tell us that our history is admirable, that it should flatter us. But our history doesn’t have to flatter us and its naive of us to expect it to. Instead, if we really are committed to forming a more perfect union, we should look to the past to better understand our inequities at present and use it as a guide to address them.

Q: Some people might not give your book a chance, saying “Here’s this guy from the Northeast telling us Southerners how to look at our history and how to think and feel.” How would you respond to those folks?

A: Look, I know that Southerners — especially white Southerners — are defensive about this stuff, but since the approach of the book is not “telling Southerners how to look at our history and how to think and feel,” I suppose I’d first ask them to accurately describe what I’m up to here. As the book makes clear, I see Confederate monuments as a Southern exponent of a much deeper American problem — one that implicates me and my Yankee brethren, too.

Q: Now that the book is completed, published and out in the world, how are you feeling?

A: They had to pry the book out of my hands this summer in order to send it to the printers. If I had my way, it seems, I’d just keep on writing it forever. But I can’t. And I’m enjoying the novelty of the book being in the world, in readers’s hands, rather than just on my computer, where it lived for years. Writing can be such lonely work, so it’s a tremendous feeling to know that the book is being read and, in some cases, resonating with readers.

Q: Obviously, you had to stop reporting at some point, but the controversy over Confederate monuments has continued. How do you think your book will impact that ongoing conversation?

A: I hope it will orient readers to the deeper systems of inequity that these statues represent and which will remain even after a statue topples.

Q: Do you think your book can be a catalyst for change?

A: I know that I’ve been changed by books I’ve read. And the process of writing this book certainly changed me, too. It forced me to be more honest about how race has shaped my life and to see more clearly the systems tilted to benefit me. It seems like we’re in a moment when more white Americans are coming to similar realizations. I hope that the journey I chronicle in this book will be relatable and compelling for readers who, like me, are scrutinizing the role of race in shaping this country and our own lives.

–al.com