SULLIVAN’S ISLAND — It was a notable defeat, and it turned the tide of the war.

The British officers who led the assault against American rebels at Sullivan’s Island in 1776 put a positive spin on it afterward, omitting facts about their bloody losses and the strategic superiority of Col. William “Danger” Thomson’s defenses.

Adm. Peter Parker referred to “unlucky accidents,” and invented some appealing details in a description of the conflict published in the London Gazette meant to fuel British patriotism.

But the truth eventually seeped out.

The editor of Maj. Gen. Henry Clinton’s memoirs called it “an egregious fiasco.”

A young army officer said it was “one of the most singular events that has yet conspired to degrade the name of the British Nation.”

Even King George III, who had greenlit the assault eight months earlier, admitted in an understated and aristocratic way that the effort had failed.

“Though the attack upon Charles Town has not been crowned with success, it is by no means proved dishonorable,” he wrote. “Perhaps I should have been as well pleased had it not been attempted.”

The British point of view of this decisive battle will be the topic of Douglas MacIntyre’s talk on Carolina Day at Charleston’s White Point Garden on June 28. The celebration, organized by The Palmetto Society, will begin at 10 a.m. with a service of thanksgiving at St. Michael’s Church. At 11 a.m., participants will gather in Washington Park, across Broad Street from the church, to prepare for the traditional parade, which will begin at 11:30 a.m.

The Palmetto Society has sponsored Carolina Day celebrations since 1777. Its board is composed of leaders from Revolutionary War heritage groups that include the Society of the Cincinnati, the Daughters of the American Revolution and the Sons of the American Revolution.

The town of Sullivan’s Island is partnering with the Battery Gadsden Cultural Center to mount a celebration of its own, starting at 9 a.m. June 25 in front of Town Hall, 2056 Middle St.

That program will include a proclamation from Mayor Pat O’Neil, the Revolutionary War story of Michael Kovats, and a ceremonial raising of the Moultrie flag and firing of a musket salute.

Afterward, starting at 10 a.m., Fort Moultrie will offer its own Carolina Day programming.

As word spread along the Atlantic Coast and reached American ears, the shockingly successful effort to repel British naval and ground forces from Charleston energized the rebel cause. George Washington, fighting in the Northeast, cited the Battle of Sullivan’s Island to inspire his troops. American patriots concerned about being overpowered by a superior and better organized British military now could better imagine a scenario that led to independence.

MacIntyre is a retired businessman and student of Revolutionary War history. His research of the Battle of Sullivan’s Island led to the creation of Thomson Park, named for Thomson, commander of a force of 780 men who repelled the British land assault at Breach Inlet.

He said the British strategy was threefold: Secure Canada, take control of the South (at Charleston), then launch an attack on New York to isolate New England and cut off the colonies — the “obstinate daughters” — from one another.

It didn’t work out.

In Charleston, the rebels consolidated their resistance. Fighters came from all over the region to help. The population of Charleston at the time was about 12,000, and there were about 12,000 troops, British and American, involved in the fighting.

On June 28, the day the Continental Congress began debating the Declaration of Independence, the British launched a two-pronged attack on Sullivan’s Island. A flotilla of ships was positioned in the harbor entrance and fired upon Fort Sullivan, which was well-protected with sand and palmetto trunks. A second line of ships trying to squeeze through behind the first group ran aground on a shoal where Fort Sumter now stands.

The volley of cannon shot was fierce, but the Americans aimed well from their fortification and inflicted huge damage on the British vessels.

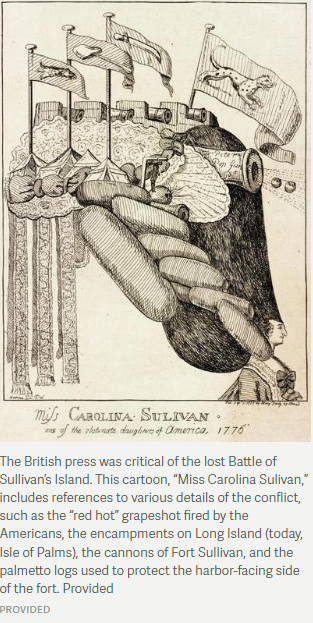

Meanwhile, at the north end of the island, British troops were stopped from crossing Breach Inlet by a barrage of grapeshot from patriots commanded by Thomson.

The height of the battle occurred on June 28, but the two sides had been preparing all that month. Fort Sullivan wasn’t fully built, only its water-facing side was protected. The British therefore hoped the land invasion would enable them to disable the fort and permit their ships from taking full control of the harbor.

It was not to be.

“It was a shocking defeat,” MacIntyre said. “It sent a shockwave up and down the seaboard.”

It was the first time the Americans beat the British in a major battle, and it proved that King George’s men were vulnerable, he said.

“It gave hope to the American cause.”

On July 4, the Second Continental Congress voted in favor of the Declaration of Independence — before its members learned of the patriot victory in Charleston. The news got to Philadelphia on July 19. The next day, the first order of business for the Continental Congress was to commend the military leaders in Charleston. Two weeks later, on Aug. 2, the vast majority of signers, 56 of them, applied their names to a parchment paper copy. By then they knew what had happened.

–postandcourier.com