BEAUFORT — Archaeologist Chester DePratter looked beyond the edge of the city. From the park at the bottom of The Point, he could see 5 miles down the Beaufort River.

“This is the highest point around,” DePratter, a research professor at the SC Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of South Carolina, said to colleagues who assembled Aug. 10 to learn more about his dig underway. “Can you see that hazy thing in the far distance? That’s Parris Island.”

The park’s dramatic location makes it a popular place for photos. But for earlier residents, DePratter reasoned, it would have been a great place to build a fort.

He poked his toe in the turf. A few feet below, he hoped to find evidence of a lost 17th century Scottish colony known as Stuarts Town.

The story of Stuarts Town

History buffs eager to educate the public about the search for Stuarts Town taped up a sign posing the natural question: What the heck is it?

Here’s the story.

In 1684, a few dozen Presbyterian Scots came to today’s Beaufort area, seeking freedom from religious persecution in Scotland.

The British noblemen who claimed the lands of Carolina welcomed the Scots. Among other things, they wanted a buffer between the English settlement of Charles Towne and the Spanish territorial capital of St. Augustine.

In a few years, the British expected thousands of Scots to settle the area.

Initially, a few hundred crossed the Atlantic to Charles Towne. Just 51 straggled onto Port Royal Island, ill and anxious about a Spanish attack.

Nevertheless, the leader of the group, Henry Erskine, Lord Cardross, imagined a thriving community.

He named the settlement after his wife, Catherine Stuart Erskine, and wrote that the group planned to clear 220 lots, each with a small adjacent farm. Within six months, the Scots, along with a few Englishmen who’d joined them, had established at least 40 houses, a church and a fort.

A fateful turn

Because almost all the Scottish settlers had been imprisoned in their homeland for their beliefs, they particularly wanted peace in Carolina. They hoped to establish friendly relations with the Spanish and become trading partners. Already they had allied with the Yamasee in the area, even providing the Natives with shotguns and pistols.

But the Spanish had a different attitude about the Scots: They saw the newcomers as intruders on their territory, which they had claimed since the time of Christopher Columbus.

In March 1686, events took a fateful turn.

A group of Yamasee, armed by the Scots, raided a Spanish mission. They killed some people, burned several towns, stole items from a church and brought back prisoners, whom they sold as slaves.

Six months later, the Spanish took revenge.

In August, they launched a surprise attack on Stuarts Town. About 150 men drove the Scots into the woods. Then they plundered the houses, slaughtered the livestock, and torched the town.

From there the Spanish troops continued on toward Charles Towne. They planned to invade the English settlement, but managed only to wreak havoc on the south end of Edisto Island before a hurricane stopped their progress.

As for the Scots, a few of the survivors integrated into Charles Towne. Most returned to Europe. No effort was made to resettle Stuarts Town.

‘Crossroads of colonialism’

For a short-lived settlement, surviving only between 1684 and 1686, Stuarts Town has attracted a fair amount of attention.

“People are always interested in the earliest examples of whatever,” said Jon Marcoux, an archaeologist from Clemson University who had come to Beaufort to learn more about DePratter’s search for Stuarts Town. His face shone with sweat as he followed DePratter through downtown Beaufort’s restaurant-and-shopping district. “In this case, (Stuarts Town) is one of the earliest colonial examples of a settlement here in the area.”

The Scots’ story also expands people’s understanding about American history, said Charles Cobb, a professor of historical archaeology at the University of Florida and DePratter’s partner leading the dig.

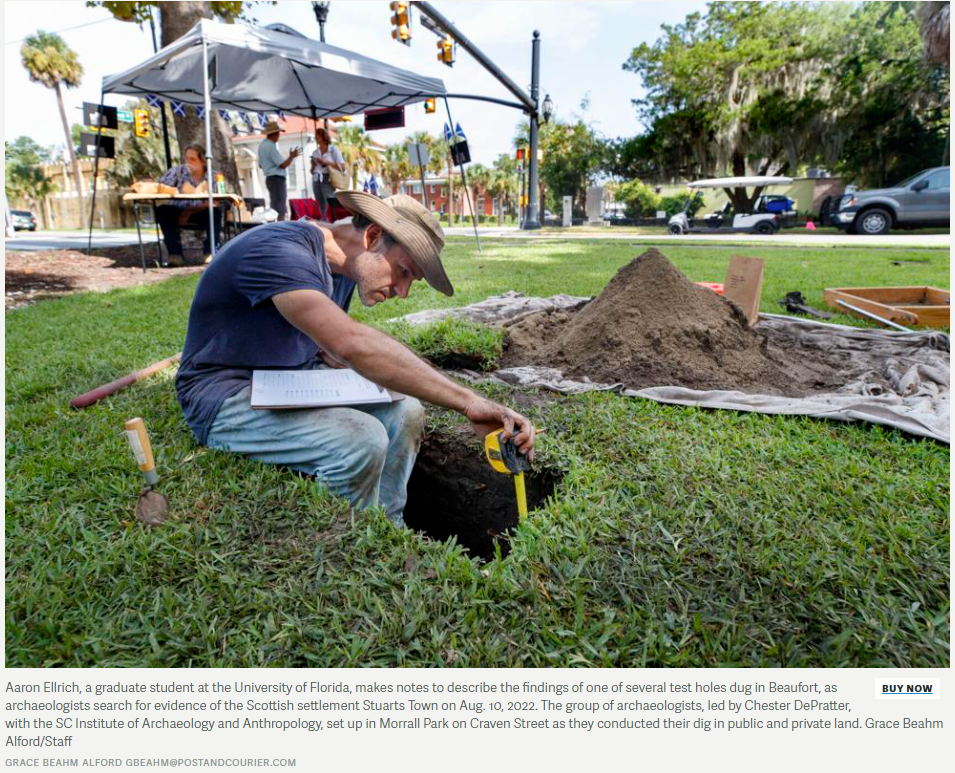

While DePratter showed visitors around, Cobb sifted dirt from a neat, rectangular hole at the busy intersection of Craven and Carteret streets. It was one of more than 100 shovel tests a team of 10 archaeologists performed in the last week across a 400-acre section of downtown.

“I think we all have the same experience whenever it gets into ‘the Puritans arrived in the Massachusetts Bay Colony,’ and ‘the first Thanksgiving,’” Cobb said. “It seems to be really one-sided.”

In fact, America’s Colonial past included many more players than just the English.

“The farther south you live in the South, you realize what an important presence the Spaniards were. The French were an important presence here, and the Scots were as well,” Cobb said. “I mean, this area was a crossroads of colonialism.”

An unexpected clue

Despite scholars’ interest in Stuarts Town, no one knew its exact location. Until recently, conventional wisdom placed it about a mile and a half down the river from downtown Beaufort, in a neighborhood called Spanish Point.

Yet evidence of it had never been found there.

On a break from his hosting responsibilities, DePratter settled onto a park bench with a homemade ham sandwich and explained that he had been curious about Stuarts Town since the late 1980s.

As an archaeologist, DePratter has been called a jack of all trades, knowledgeable about South Carolina from thousands of years ago to the 1800s, and everything in between. But he has a particular reputation as an expert on Colonial times. In 1995, he helped find remnants of a 1562-63 French settlement at Santa Elena, on today’s Parris Island. A few years ago, he uncovered evidence of the 1577 Spanish fort of San Marcos in the same area.

Earlier in his career, DePratter hadn’t exactly expected to look for Stuarts Town. But in 2000 he attended a conference at the College of Charleston and found himself sitting next to a researcher who studied Scottish colonies in America.

“And he said, ‘Oh, I’ve got a map. You might be interested,’” DePratter said.

A few days later, the researcher emailed DePratter the map, created centuries ago in Carolina, sent to England, and filed in some archives. It seemed to show Stuarts Town below today’s downtown Beaufort.

“So I’ve been sitting on that map for 22 years waiting to come do this,” DePratter said. “This is a search to see if we can find clues as to whether it’s really there.”

Artifacts, including broken pottery and glass, have been found by Gwen Myers over the years in the yard of her Bay Street home in Beaufort. Archaeologists are digging in her yard as they search for evidence of Stuarts Town, a Scottish settlement that existed from 1684 to 1686, which dates much later than the pottery and glass bottles found in Myers’ yard. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Grace Beahm Alford gbeahm@postandcourier.com

In a best-case scenario, DePratter can imagine finding the perfect artifact.

“Maybe we’ll get lucky. We’ll dig a hole and we’ll hit a burned floor and then we’ll find a glass bottle embossed with the name Henry Erskine, Lord Cardross.”

But that’s unlikely.

For one thing, the Scots simply didn’t occupy Stuart Town long enough to lose or throw away a lot of material goods, DePratter said.

For another, whatever comes out of the ground will be dirty. Identifying it will require washing and examination. Even if archaeologists uncovered the perfect artifact, it would be a matter of weeks before “we could say yes or no, we think we found Stuarts Town,” DePratter said.

Putting the town on the map

Three days into the dig, the team had mostly found modern-day detritus: nails, oyster shells, a broken whiskey bottle.

As far as earlier artifacts went, there was some whiteware pottery from the early 1800s, Cobb said.

But he didn’t expect to uncover too many intact objects from Stuarts Town anyway.

“The Scots abandoned the place so rapidly, they were leaving their dinner on the table, that kind of thing,” Cobb said. Given that scenario, Cobb thought archaeologists might find carbonized wood, with household goods buried in the mix. “The smoking gun we would be looking for is burns.”

“We’re looking for a layer of charcoal, essentially,” DePratter said.

Larry Koolkin, coordinator of the Stuarts Town Action Group, supports archaeologists as they search for evidence of Stuarts Town in Beaufort on Aug. 10, 2022. Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Grace Beahm Alford gbeahm@postandcourier.com

But it’s always possible the team won’t find anything at all. As DePratter describes it, archaeology requires tremendous patience and persistence for an outcome that may never materialize.

So what motivates people to put in the hours, peering into dank pits during some of South Carolina’s hottest days?

“That’s how knowledge proceeds,” DePratter said. “People don’t want to go into (a museum) and see a bundle of things without any good information on where those things came from or how they fit into the big picture. … Putting places like Stuarts Town on the map makes it a more complete record.”

Right now, DePratter said, few people even know Beaufort had a Scottish settlement. He hopes that by interpreting some of the subtle clues about the past, providing context to pieces of ceramics or metal or glass, he can provide a clearer history of this part of the world.

“You can say, ‘This was taken to Stuarts Town by Scots, destroyed by Spaniards in 1686 and then found by archaeologists in 2022.’”

–postandcourier.com