Spend any amount of time talking about slavery on the internet, and you’ll eventually encounter the claim that there were “black Confederates” that fought for the South. “Over the past few decades, claims to the existence of anywhere between 500 and 100,000 black Confederate soldiers, fighting in racially integrated units, have become increasingly common,” writes historian Kevin Levin in his new book, Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth.

“Proponents assert that entire companies and regiments served under Robert E. Lee’s command, as well as in other theaters of war.” Look, believers say (directly or subtextually): The Confederacy can’t have been so bad for black people. Otherwise, why would they have defended it?

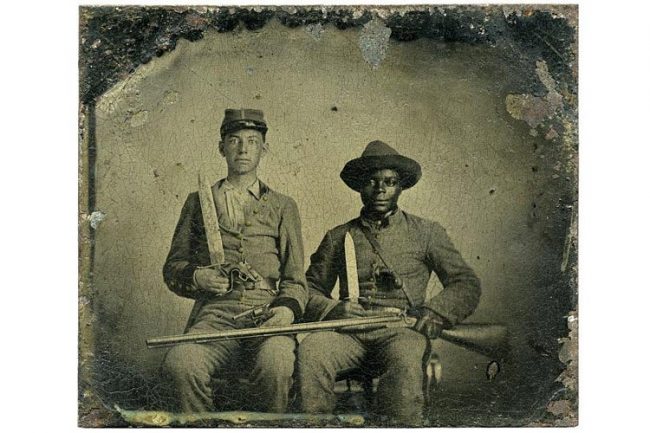

Sergeant A.M. Chandler of the 44th Mississippi Infantry Regiment, Co. F., and Silas Chandler, family slave, with Bowie knives, revolvers, pepper-box, shotgun, and canteen

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Levin’s book explains how this myth came about—while neatly dismantling it. We spoke recently about actual Confederates’ perspectives on black soldiers; why former “body servants” attended Confederate reunions during Jim Crow; and how the World Wide Web gave this story legs.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Rebecca Onion: I can see from following your Twitter that you sometimes engage with people who believe in this myth. And you’ve been researching it for a decade or so. What are the major pieces of evidence that people most often bring to you as “proof”?

Kevin Levin: If you’re browsing online, there are literally hundreds if not thousands of websites dedicated to promoting this myth. And on many of them, you’ll find photographs of enslaved men in uniform, which are easily interpreted as “proof” of the existence of black Confederate soldiers. Certainly there are plenty of newspaper accounts, mainly from Northern newspapers published during the war, that seem to suggest black men were fighting as soldiers. There are photographs taken after the war of some of these former “body servants” attending Confederate veterans’ reunions and monument dedications. Sometimes you’ll hear or read references to pensions given to black Confederate “soldiers,” which in fact were for former camp slaves or “body servants.”

There are some bits of evidence that are straight-up faked, like a supposed photograph of the “Louisiana Native Guard,” which is actually of black Union soldiers. But in a lot of cases it’s not about fakery, and more that the social context surrounding the evidence isn’t being considered, right?

Yes. The best example is on the cover of my book, which has a photo of Andrew and Silas Chandler: two men, both in uniform, one black and one white. They both appear to be heavily armed, and what more evidence could you possibly need for the existence of one black Confederate soldier? It’s an iconic photograph, one of the most popular photographs of the Civil War.

Silas, the African American in the photograph, was born enslaved into the family. He moved as a child with the family from Virginia to Mississippi. In 1861, when Andrew volunteered for the 44th Mississippi Infantry, like a lot of other officers from the slaveholding class, he brought with him what they would have called “body servants”—what I call in the book a “camp slave.”

And the camp slave essentially existed outside the military hierarchy. He functioned as the personal slave of his master—in this case, Andrew. He would have been tasked with cooking, with cleaning, with packing up camp for long marches, carrying supplies, and serving as a messenger between camp and home. Even assisting on the battlefield at times. If necessary, even rescuing the master from the battlefield or escorting the body home in the event of his death. There were thousands of these men in the Confederate Army, in addition to tens of thousands of impressed slaves that performed all sorts of other functions.

Silas was with Andrew until the latter was wounded at the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1863; he escorted Andrew home. Silas had a wife and newborn child back home in West Point, Mississippi. And for a brief period of time he was present back on the plantation, until Andrew’s brother Benjamin enlisted and went off to war in a Mississippi cavalry unit. So Silas went off to war again, escorted him and served as his “body servant.” Interestingly enough, Benjamin’s unit was responsible for escorting Jefferson Davis out of Richmond after the Fall of Richmond. And so Silas was literally in the war from the beginning until the very end.

The photograph, which was taken in a studio, shows Silas loaded up with weapons that you write were most likely props. He was never a soldier, per se. And when it comes to the experiences of many of these camp slaves, you mention that there’s a number of pieces of evidence that some of them used the chaos of the war to work for their own interests—to make money, or to run away.

Yes, one of the things I found most interesting is trying to understand what happens when you pluck the master-slave relationship from the setting of the plantation, where the expectations are set, into a new environment. Andrew had never been off to war; Silas had never been off to war. How does that relationship stretch and contract in relationship to some of the uncertainties of camp life, long marches, and especially the battlefield?

And what I found is, not surprisingly I guess, enslaved men like Silas and others used that opportunity to gain increased privileges. So when they had free time they would work for money, doing odd jobs for other people. Some of them end up buying their own uniforms for any number of reasons. They’re able, some of them, to send money home to their families. Some of them stretch the relationship to the breaking point and end up running off, either to the Yankee army or elsewhere.

On the flip side, you get to see how Confederate officers, their masters, end up having to push back, and try to regain control over this enslaved individual. And obviously many of them do so in the most violent way. There are a couple of accounts in the book that are just harrowing.

And in one way—and I think more research needs to go into this—I get the sense that when you watch this dynamic play out, you’re actually watching the unraveling of slavery. Historians have written about the ways that, on the home front, you see slavery unravel as the war progresses. Depending on whether all the men are away fighting, and the location of the Union Army, you see how everything breaks down. But I think even in the Confederate Army itself, you can see how slavery unravels relationship by relationship.

The Confederate common wisdom at the time about those enslaved people who ended up experiencing combat directly was that they were not very brave.

Confederates had to preserve a paternalistic assumption. It was in the very nature of white supremacy, at least as it was wrapped up in slavery, that white men embodied the intelligence, moral character, bravery, martial virtues, honor, [all] that’s necessary to fight on the battlefield. When white Confederates were exposed to their “body servants” displaying what they’re tempted to call bravery on the battlefield, this was a problem because they were not supposed to be doing that. And so what they ended up doing in many cases, is they ended up ridiculing them. So if they did see them fleeing in the face of artillery and shelling, they’d take advantage of it and really poke fun at them, because it’s a way of reinforcing their own sense of Southern honor. Even though, if you’re talking about shirking, desertion, fleeing the battlefield…whites experienced all the same things.

One of the weird things about this history and its relationship to the myth is that there was a moment late in the war where people inside the Confederacy actually did argue over whether to bring enslaved people into the army as soldiers.

As someone who has dealt with people who believe this narrative, I’m always struck by the fact that they seem to be completely unaware that the Confederacy openly debated this issue throughout most of 1864 and early 1865. It was a very public debate! There were literally hundreds of newspaper editorials, letters, and diaries from people in the army writing about this. The soldiers themselves were glued to this issue. Entire regiments issued statements on where they stood.

And what’s remarkable to me is that no one involved in this debate at the time, regardless of their position on the enlistment of slaves, ever pointed out, “Hey, black men are already fighting as soldiers on the battlefield.” So forget about whether or not anyone has ever heard of an enslaved man picking up a weapon on the battlefield or wearing a uniform and marching with the army. No Confederate saw any of this as reflecting service as a soldier.

In talking about enlisting slaves, the Confederacy was debating a fundamental point about its existence and the meaning of what they were fighting for. Plenty of people were convinced: “If you go this route, that’s the end of it! What kind of victory are we ultimately talking about here? A victory without slavery is no victory at all.” Even most of the people who agreed on some kind of enlistment weren’t doing it because they wanted to end slavery; they thought they could get away with some kind of limited emancipation. Maybe they could free the people who do fight and their immediate families. But very few people saw this as a push toward general emancipation.

Now, in 2019, there are some neo-Confederates who are saying, “No, the black Confederate myth is wrong because black people could never have been brave enough to fight in our army.” So this is coming full circle.

That’s right! The most extreme conservative neo-Confederate organizations, like the League of the South, call people who believe in the “black Confederate” myth “Rainbow Confederates.” They’re like, “We were racists! Let’s not hide this!”

It’s funny, because in a sense they’re the ones who are historically sound! It’s horrifying to think of it, but they are absolutely right [about the nature of black men’s involvement with the Confederate Army].

The stories of elderly former camp slaves who attended Confederate reunions as “veterans” in the Jim Crow era are hard to square with. These were black men still living in the South, who would go so far as to make themselves into quasi-minstrel characters to appear at reunions. You write that they often played the decidedly non-martial role of “the forager,” whose main job was stealing food for the cookpot—they carried chickens under their arms, and so forth. I don’t know if we can know these men’s motivations. What were they getting from this?

I think to certain extent it at least gave them a certain kind of agency. I do get a sense that they understood what was expected of them. As a historian you’re trying to understand their motivation through the lens of these white Southerners, and that’s hard to do.

Because the reports we have about these reunion attendees are coming from white observers.

Yes, that’s it. You get the sense that the former camp slaves believed they were going to get something out of it. Maybe they were looking to shore up their place at home, stay in good standing with local Confederate veterans who were now leaders. Some of them who attended the Confederate reunions did so for monetary reasons. They were able to earn a little bit of money entertaining.

They were performers.

Yes, it did sort of border on, if not fully embrace, minstrelsy. With someone like Steve Eberhart Perry from Georgia, I think there is some evidence to suggest he clearly understood the role he was playing, in the way he adopted different surnames. So when he’s at these veterans’ reunions, he’s “Uncle Steve Eberhart,” using the last name of the master he went to war with; at home he’s “Steve Perry,” using the surname the rest of his family uses. And he attended multiple reunions. You find him all over newspapers and in plenty of photographs. He carries chickens. He says things like, “I was always the white man’s n****r.” He plays that up to a T. I have to imagine he was getting something out of it.

There might have been personal reasons as well. I think some people are going to have problems with this argument, but I think … you can’t forget the master-slave dynamic, but you can’t deny that they did forge some kind of bond during the war. They did have to experience some of the same hardships: long marches, winters in camp, lack of food, disease. And I think those bonds probably survived the war. I think some of these former camp slaves wanted to be around—maybe not their former masters, but wanted to continue a relationship they developed during the war. I think something along these lines can be said for these white veterans as well.

That doesn’t mean this is some kind of interracial love fest. It certainly wasn’t. But I think there’s an element of that we have to come to terms with, even as we acknowledge that these men occupied a significant space in terms of their symbolic importance. They were living reminders, not just for the veterans, but also the white southerners who didn’t experience the war, of the Lost Cause. And most importantly, during the Jim Crow era, they were a visual reminder of the kind of behavior expected of African Americans at the time: “Know your place in the racial status quo.” And they did.

You wrote something similar about the decisions to extend pensions to former camp slaves. At a time when there was no money from the state for impoverished black people, here’s the way to get money—but only if you served us.

The initial push for these pensions came from the Confederate veterans themselves. But the states didn’t end up passing them until the early 1920s, when only a few former camp slaves were still living to take advantage, and the amount they were being paid paled in comparison to what white Confederate veterans were receiving. But still, there was nothing else like it at that point in time.

Fast-forward to the civil rights era. The “black Confederates” myth blew up when the web got ahold of it. But the narrative the web amplified, you argue, was already percolating in the ’70s.

Yes, that’s right. Just to reiterate an important point, there was no reference during the war or even in the postwar period, through the 20th century, to the idea of “black Confederate soldiers.” In the seventies was when you see this shift from referring to these men as “body servants” to actual Confederate soldiers.

Coming out of the civil rights movement, new scholarship was beginning to filter down, historic sites were beginning to address the issues of slavery and emancipation, Roots was a hit, and we were starting to learn a bit about the United States Colored Troops in the Union Army. Neo-Confederates saw it as a threat, and they wanted to make sure they could balance the scales, if you will—and how do you do that? Go out and find your own brave black Confederates. The myth was percolating through the ’80s, responding to the success of the movie Glory, and also Ken Burns’ Civil War series—which, as Lost Cause–y as it is, they saw as a threat because it was dealing with slavery. And the public was eating it up. So the Neo-Confederates needed to come up with a response.

You’re white, unless I’m much mistaken!

Yes, that’s right.

Is it hard for you, as a white author, to write about black people who believe in and perpetrate this myth? You’re saying they’re wrong about the interpretation of this evidence, while on the other hand, it’s their history. That’s a delicate position to be in.

One thing I learned from the late Tony Horwitz is when it comes to understanding memory and how people try to make meaning of the past, listen. And listen carefully. And do your best not to prejudge. As bizarre as I think someone like H.K. Edgerton is, and opportunistic, and just downright silly at times, I hope that I’m able in the book to take him seriously. Ultimately, I think we are hard-wired to try to come to terms with history in a way that helps us make meaning of our own lives and the world around us. And I want to honor that.

Think of people like Mattie Clyburn Rice, the daughter of a former “body servant.” Her story, as far as I’m concerned, was co-opted by the Sons of Confederate Veterans and used to further their propaganda. But I don’t think it’s that difficult to understand why the descendants of Weary Clyburn might embrace this story. Think of the extent to which the African-American story in relationship to the Civil War had just been ignored throughout most of the 20th century. And when it’s been addressed, it obviously comes mostly in terms of enslaved people. And certainly, coming out of slavery there were African-American families who just simply didn’t want to talk about the story of slavery, or pass these stories down to the next generation.

So now you have an organization that wants to honor your ancestor with a military ceremony, with all the pomp and circumstance that people who are valued because of their honor and bravery receive. I can certainly understand why a family would jump at that opportunity and embrace it. It’s just that unfortunately, at the same time, that embrace allowed for the reinforcing of this false narrative, the myth that in so many ways has distorted the story of African Americans—not just in the Civil War, but beyond.

–slate.com