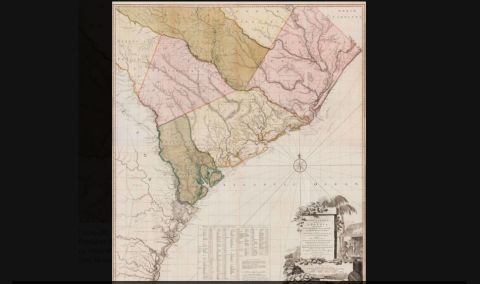

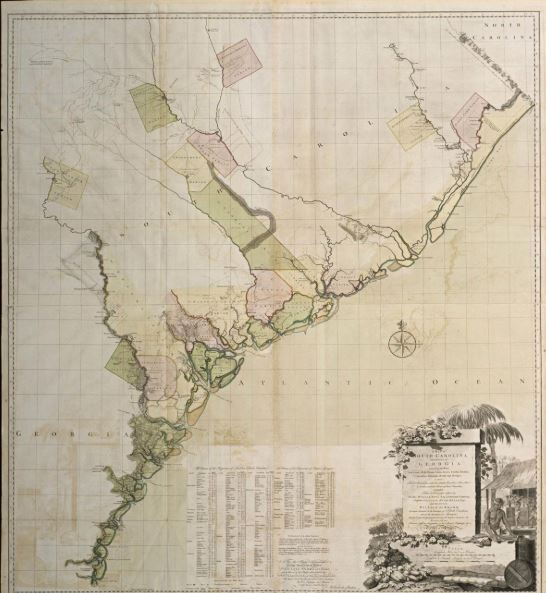

The large, colorful map of South Carolina and part of Georgia acquired recently by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation details much more than the geography of those states at the dusk of the colonial era.

The very rare 1780 map is valued largely because it updates a 1757 version drawn by the cartographer William Gerard De Brahm and published by Thomas Jefferys, geographer to King George III.

Comparing the two provides all sorts of insights into the mid 18th century history of the two colonies, including:

- How both expanded in the few peaceful decades between the French and Indian War and the start of the Revolutionary War.

- Which new settlements emerged on their western frontier between 1757 and 1780 and how they impacted Native American tribes.

- The social standing of prominent land-owning colonists whose names are listed.

- The state of scientific understanding of which parts of the state were best positioned for agriculture.

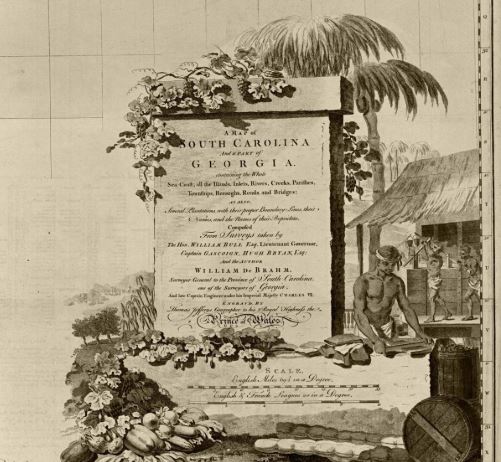

This 1757 map by 1973-322; Map of South Carolina and part of Georgia Colonial Williamsburg Foundation/Provided

“De Brahm’s 1757 map is really considered the definitive map of South Carolina and Georgia for the time — for its accuracy, particularly of the coastal regions,” said Katie McKinney, the foundation’s assistant curator of maps and prints.

Born in Germany in 1717, De Brahm served as a military engineer in Bavaria until he was expelled for renouncing his Catholic faith. He then joined a group of 156 German Protestants who settled Ebenezer, Georgia, in 1751.

His skills quickly became known, and a year later, South Carolina Gov. James Glen tapped De Brahm to design and build fortifications for Charleston. Two years later, De Brahm became the state’s surveyor general.

His 1757 map meticulously represented settlements, land quality, climate, coastlines, waterways and soil types. Its large swaths of land with nothing delineated also shows the potential for new settlement.

McKinney noted all of the significant 18th century maps of South Carolina are derived from the 1757 De Brahm map, including James Cook’s 1773 map, Henry Mouzon’s 1775 map (on display in the Charleston Library Society), and then the updated map published by William Faden in 1780.

“In terms of accuracy for the region, it was unparalleled,” McKinney said of De Brahm’s map. “According to one of the leading scholars on the map, Louis De Vorsey, the map was so accurate that it was used as evidence in a 1990 court case between South Carolina and Georgia in a U.S. Supreme Court case regarding the boundary of the lower Savannah River.”

McKinney said a few other copies of both very rare maps exist, though she could not say how many. “We’ll certainly will be working on that in the coming months,” she said. “This map does not appear on the market very often.” The foundation did not disclose what it paid.

Ronald Hurst, the foundation’s chief curator and vice president for collections, conservation and museums, said Colonial Williamsburg sought the map because of its inherent beauty, as well as its documentation of historic people, places and events.

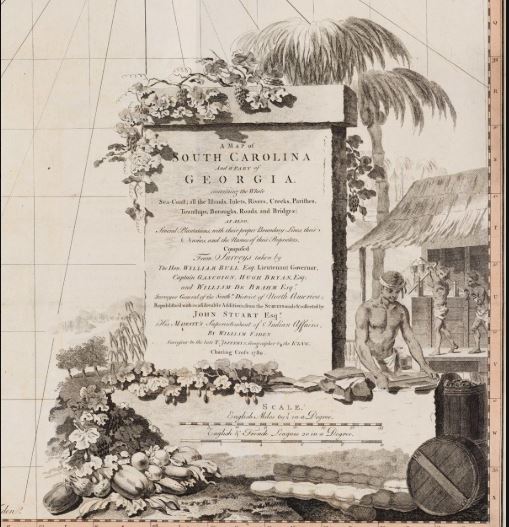

Both the 1757 and 1780 maps feature a cartouche or decorative emblem showing palmetto trees, flowers, fruits and vegetables as well as images of three slaves at work.

“The cartouche depicts a rather sanitized view of slavery,” McKinney said. “They are processing indigo, which along with rice were incredibly profitable for plantation owners in South Carolina.”

The 1780 map measures 4½ feet by 4 feet and had to be combined from four smaller prints since they couldn’t make a single piece of paper that large. It also is considered to be in excellent condition.

“The color is extraordinary,” she said. “It doesn’t seem to have seen a lot of sunlight.”

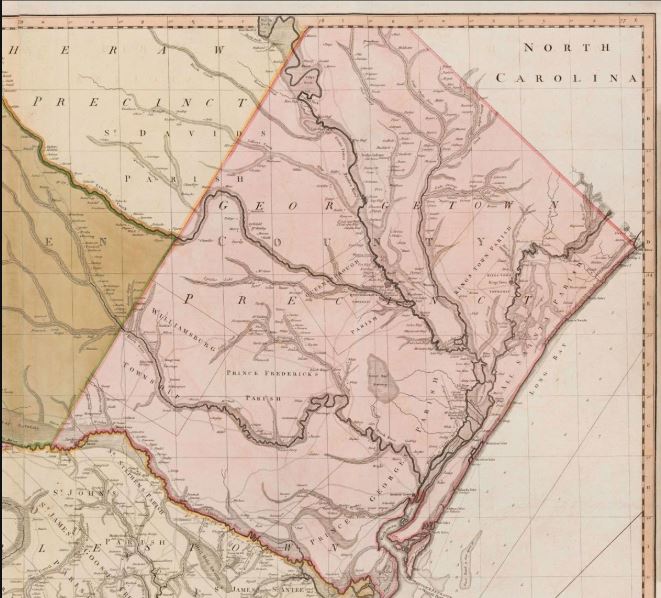

McKinney noted the blank space on the 1757 map is one of its defining features, but that area is increasingly filled in on the updated version 23 years later, a version that started with the same copper plates.

The Georgetown Precinct in the state’s northeastern tip flourished because of indigo and rice production in the period between the two maps and has extensive revisions in the 1780 version.

The 1780 map also shows more detail on roadways, landowners and settlements.

Faden’s changes, which were so extensive that some argue he made a different map, not just an updated one, were based on surveys gathered by John Stuart, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Southern District in the 1760s and 1770s.

Stuart, who had a wife in Charleston and also fathered a child with a Cherokee woman, often complained that he didn’t have an accurate backcountry map, McKinney said.

“Stuart was instrumental in negotiating and maintaining peace with Native Americans,” McKinney said, “and much of his work involved determining boundaries and attempting to regulate European settlers who were trying to settle outside those lines.”

When De Brahm started making map in 1750s, he advertised in a newspaper asking landowners to send surveys of their property that he could include in his map. Many did.

“If your name appeared in the lower table on the map, that meant you were quite important,” McKinney said. “The second map adds more names that indicate land ownership, houses, and towns.”

The foundation plans to have both maps on display by next spring at the latest, as construction winds down on a new maps and prints gallery for the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg.

The South Caroliniana Library at the University of South Carolina also has copies of both the 1757 and 1780 maps stored in its Kendall Map Collection, library spokeswoman Kathy Dowell. They’re not on display but can be seen upon request with a day’s notice.

Eventually, Colonial Williamsburg plans to use the 1780 Faden map with the 1757 map and other three dimensional objects to illustrate the movement of cultural groups from the coast to the sandhills and foothills, Hurst said.

–postandcourier.com