This story, seldom told, begins at a wharf reaching hungrily toward the sea. But not Gadsden’s Wharf or any that you’ve likely heard of.

Instead, it opens at Col. William Rhett’s wharf, forgotten now, due to intent or neglect.

To find the ghost of it, stroll away from East Bay Street’s leafy restaurants, down a narrow brick lane called Middle Atlantic Wharf, and toward the harbor. Waterfront Park stretches its green arms to you. Nearby, the iconic pineapple fountain burbles in welcome.

Most days, the water beyond shimmers with the glittering promise that has long beckoned men like William Rhett, eager to build their fortunes. Remains of his wharf are buried here somewhere in the silt of memories, along with so many important but forgotten places on Charleston’s peninsula. They are key to understanding how this city — so perpetually ranked America’s best — became what it is today.

In the year of the city’s 350th birthday, The Post and Courier set out to salvage a few of these stories, focusing on those central to the history of African Americans, the exploited people who literally built Charleston but whose contributions and travails have too often gone ignored or suppressed by those who chronicled it.

Rhett’s wharf, and the people who disembarked onto its planks, are a prime example. Most of what tourists and schoolchildren learn of Rhett relates to his military heroics, high-seas escapades and finely preserved historic house. A marker in the front yard tells that story.

Another popular tale recounts how Rhett captured Stede Bonnet, the “Gentleman Pirate,” later hanged in White Point Garden. A marker tells that story, too.

But back up.

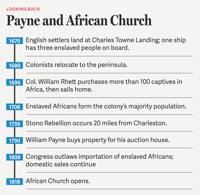

One of Rhett’s key contributions to Charleston’s history began before all that, around 1696, after he stopped in London to get his frigate retrofitted for a new kind of cargo, then set sail for Africa. Since the city’s birth in 1670, White men had imported enslaved people, but not on a large scale. Rhett thought bigger.

When he arrived back in Charleston Harbor, 165 enslaved Africans were chained on board. Veering into the Cooper River, he steered toward his wharf, the second and largest of only two built at the time.

In those moments, he was among the first — perhaps the first — White man to travel straight from Africa to Charleston with a ship full of captives destined for sale. It marked the opening bell of a mass commerce that would come to define the city.

No marker at the site tells that story.

Yet, thousands of slave ships followed. A decade after his cargo emerged from the dank belly of his Providence, more than half of the young colony’s residents were enslaved.

As they bore children and as masters died, requiring their estates be sold, in stepped a new player: the auctioneer.

Among them was William Payne, who sold upward of 10,000 human beings over a career that you’ve likely never heard of.

William Payne once handled the auctions of some 10,000 enslaved people from his business at 34 Broad St. Today, the building’s tenants include a bank whose offices span his building and the one beside it. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

William Payne’s auction house

Payne’s story lurks along busy Broad Street in a spot that’s now home to a bank. History here has preserved grand places like St. Michael’s Church and The Exchange building, which housed a public meeting space, market and dungeon.

A key business that sprouted up between these bookends, however, has gotten lost in the bustle and beauty of what once was Charleston’s commercial hub.

On The Exchange’s shadier north side, human beings were sold en masse just a few hundred steps from Rhett’s wharf, while smaller sales took place along the surrounding streets. The din of auctioneers’ prattle, the callback of eager buyers, and the agony of people for sale filled the city’s core. The enormity of interest created horse-and-carriage traffic jams.

Men like Payne set up shop to meet demand.

In 1790, as a young man dreaming of riches, he purchased two parcels that today form 34 Broad St.

The four-story building, made of red brick with handsome arched doorways and windows, stood shoulder to shoulder with neighboring buildings. Payne could step outside into the city’s salty air and see The Exchange, where President George Washington once stood on the wide front steps, or easily dart over to hold an auction.

People in period dress stand on the front steps of the Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon just a few doors down from where William Payne opened his auction house on Broad Street. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

It was perfect.

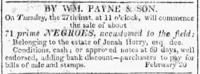

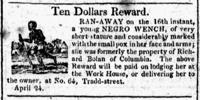

He married the daughter of a slave trader, hung out a shingle and began placing newspaper ads in earnest.

That first year, he auctioned off at least 100 enslaved people. Two years later, that jumped to 349.

By 1809, Payne advertised almost 600 human lives. A half-dozen years later, he reached 1,118. Some days, his ads stretched down almost entire newspaper columns in the City Gazette and Charleston Courier.

“A prime country born Negro GIRL, about 16 years of age.”

“71 prime NEGROES, accustomed to the field.”

“A prime WENCH, as good a cook as any of her color, with her two Sons, one 5, the other 3 years old.”

Sometimes, Payne invited potential buyers to stop by his office for a more intimate look. Regarding one mother and her four children, one 10 months old, he offered: “They may be seen at our office, between the hours of 11 and 2 o’clock, for a few days.”

Payne, with his wife and four children, lived on the floors above the office. His kids played along the streets where the carriages of interested buyers parked to attend auctions of children their ages.

When two of his sons reached adulthood, they joined the business.

Then, Payne hit his zenith. After John Ball Sr. died in 1817, Payne landed the job of auctioning off the wealthy planter’s estate. His newspaper ads for it listed seven plantations and “about 360 Negroes,” his largest auction yet, the people alone worth about $6.4 million today.

And so it went for the 70 years that he and his sons operated out of the building.

Today, most of the structure remains standing, although the front face of it, with the big white columns, is newer. Some neighboring buildings, including one next door that houses the Blind Tiger Pub, look remarkably like they did back then.

The Exchange building, of course, remains carefully preserved. People in period dress often stand on the front steps regaling passersby on the busy intersection of Broad and East Bay. A marker on one side now describes the mass auctions, a step toward remembering what happened there.

But the endless tourists and locals who stroll just a few doors down along Broad Street, past Payne’s auction house, surely have no idea of what he did inside.

African Church

Along with the riches gleaned from enslaved Black labor, Whites like Payne saw another big wealth opportunity, this one plumbing the riches of heaven.

As part of a mass campaign of evangelism, Christian masters let enslaved people into their churches, albeit segregated in the balconies. From their pulpits, White ministers could deliver selected Scripture to Black ears:

“Servants, be obedient to them that are your masters according to the flesh, with fear and trembling, in singleness of your heart, as unto Christ.”

Payne himself co-founded the Charleston Bible Society.

But as he prepared to auction John Ball’s estate, something huge was happening in the church world. A free Black preacher named Morris Brown had led a mass exodus of 4,367 worshippers — free and enslaved — out of the White Methodist churches.

It was an audacious move, one that historian Bernard Powers would later describe as “a rebellious act of revolutionary proportions.”

Now, the Black Christians moved into their own house of worship. The building, almost certainly a wooden one, sat at the corner of Hanover and Reid streets in an independent village just outside the city limits. Then called Hampstead, today the area is part of the gentrifying, mixed-race East Side.

Several decades before the church opened, fine houses had dotted Hampstead. Those had since been torched during the Revolutionary War and, now in the dusk of the War of 1812, the Black congregants took advantage of an area in transition outside the city limits.

As sacred songs filled their new spiritual oasis, called the African Church, Black leaders taught the Gospel.

Among them was a free man named Denmark Vesey.

Unlike the mostly enslaved people worshipping in the space, Vesey could read the Bible for himself. And within those gossamer pages, he discovered a different message. In Exodus, he found a call to freedom:

“He that stealeth a man, and selleth him, or if he be found in his hand, he shall surely be put to death.”

A house with a white picket fence now stands at 50 Reid St., where once the African Church provided spiritual solace to Black residents, free and enslaved. Whites tore the church down after the foiled 1822 slave rebellion reportedly was hatched among church leaders and worshippers. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

As Whites grew increasingly alarmed, the City Guard reached outside its jurisdiction to raid the church, arresting and beating worshippers and ministers, even a bishop. Enslaved people made up a majority of the city’s population; any coordination among them could spell serious threat.

Indeed, inside the African Church, dreams of freedom soared untethered. So did plans.

On July 14, 1822, a vast network of Black residents would rise up, gather a cache of hidden weapons and steal others, kill their White masters, then sail for freedom in Haiti.

As the date approached, however, several enslaved men who caught wind of the plot went to authorities. Word spread, sending Whites into a panic as police rounded up alleged conspirators, including Vesey.

He would never again see the African Church. Whites would later tear it down, paving the way for a cozy three-bedroom house with a white picket fence that stands on the spot today.

Instead, in summer 1822, Vesey and his alleged co-conspirators entered the brick walls of what some people called the Sugar House. Most called it the Workhouse.

The Workhouse

“I have heard a great deal said about hell, and wicked places, but I don’t think there is any worse hell than that sugar house.”

That’s how an enslaved man named Jim described his time there. The hulking structure on Magazine Street towered next door to the Old City Jail, which remains standing today. Some people call the jail the most haunted place in Charleston. But perhaps, really, the tormented spirits have merely traveled over from next door.

Today, only specters of the Workhouse remain.

But that hot summer of 1822, Vesey and his co-conspirators — along with more than 100 others arrested — arrived at its gate.

The three-story building, a brick fortress topped with two towers, glowered from above. A gate ushered them through a brick wall topped with pointed iron bars and broken glass.

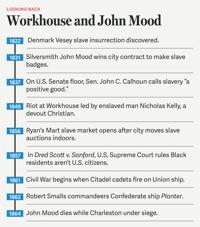

On a typical day here, prisoners arrived for committing such offenses as trying to flee their enslavers, disobeying, getting caught out working without slave badges, and other wrongs that required “correction.” Originally built in 1738 to house poor people, the Workhouse had transformed over the years into a house of punishment.

Once inside, some of the conspirators were shoved into cells crammed full of sweat-soaked people piled on top of one another. Others were thrown into the dungeon’s perpetual darkness.

Wherever the detainees went, guards ultimately dragged each to the most dreaded chamber: the whipping room.

There they faced an array of torture devices: paddles, whips, cat-o’-nine-tails and the blue jay, which had two thick lashes made heavier with knots that pounded holes upon striking flesh.

Instilling fear wasn’t the only motive for operating this place.

The notorious Workhouse once stood next to Charleston’s Old City jail. Built in 1738 to house the poor, it was transformed into a house of punishment. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

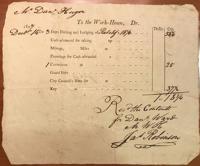

The Workhouse was a public institution. Its services also filled city coffers.

Fees the city charged slave owners generated a key revenue stream. In 1822, the city reported collecting $181 in Workhouse fees. Two years later, that almost doubled. Twenty years later, those fees brought in $5,612.83. That’s about $178,000 in today’s dollars.

In this environment, Vesey and the others faced torture and a sham trial that took place inside the building’s thick walls. The mayor brought in seven judges but no jury to hear the charges. Black witnesses testifying about the alleged plot faced extreme duress.

Only the White authorities’ trial transcript survives. Modern historians such as Nic Butler at the Charleston County Public Library continue to question the motives of the authorities and the veracity of witnesses as they ponder the true extent of Vesey’s plot.

The city charged slave owners fees for housing and “correction,” the term used for torture inflicted on enslaved people. This 1807 receipt was written to Daniel Huger for an enslaved man named Ratclif. Courtesy of the South Carolina Historical Society

“Was Vesey a criminal, or was he simply caught up in a web of racial vigilantism?” Butler asked.

Five days after Vesey’s arrest, the judges declared him guilty. From their shared cell, Vesey and his lieutenant Peter Poyas urged their collaborators to “die like a man.”

Just after dawn on July 2, guards hauled Vesey and five others from the Workhouse to their executions.

They likely were hanged about 2 miles away at Blake’s Lands, an untamed expanse that began roughly at Meeting and Line streets. It was a place where residents were allowed to dump the carcasses of their horses, cows and dogs.

Vesey might have died somewhere out there, but the site of his burial remained an alluring mystery.

Rumors spread that he in fact was executed in the Hanging Tree, a large oak that bisected Ashley Avenue. Although there’s no evidence of that, at least one formerly enslaved man relayed to an interviewer in the 1930s that the tree was used for lynching. A tree still stands on the spot, but it is a replacement planted in 1980.

Indeed, it would have been more accessible to the Workhouse’s hangmen — and to the city potter’s field — than Blake’s Lands.

Rumors persist that Denmark Vesey was executed in what’s often called The Hanging Tree near Ashley Avenue and Fishburne Street. That’s unlikely, although one slave narrative says the original tree was indeed used for lynching. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

In all, 35 men were executed, many of them members of the African Church.

There is no marker where the house of worship once stood even though “few historical sites in Charleston are more overlooked or more important,” historian Ethan J. Kytle, co-author of “Denmark Vesey’s Garden,” said.

Nor does anything mark the Workhouse, razed after the 1886 earthquake damaged it.

Instead, Whites used the plot to embark on a campaign to further restrict Black residents’ freedoms. Among the new rules: Only White ministers could teach the Bible.

So, a group of Black Methodists approached the Rev. John Mood, a respected silversmith in town: Would he teach their Sunday school classes?

Mood agreed.

That year, he also took on another new job. He won the city’s annual contract to make its slave badges.

Two of John Mood’s slave badges are on display at Charleston Museum. In the top center, Mood’s copper badge lists the city, registration number, occupation and year. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

John Mood’s silversmith shop

John Mood worked at a shop on King Street with his brother, transforming molten silver into fine goblets, knives and spoons.

Although he made fancy things for fancy people, Mood himself was not one. He and his wife raised their children with “utter contempt,” as one son later put it, “for anything of the kind so far as personal use was concerned.”

But Mood needed an income. He’d spent six years as an itinerant preacher spreading the Gospel for a fledgling Methodist church, which preferred its ministers support themselves.

Starting in late 1831, he supplemented his silversmith income making slave badges. The utilitarian pendants, often made of copper, varied in shapes and sizes each year. Over the coming years, Mood would produce upward of 7,000 of them.

Charleston Museum has on display a teacup featuring silversmith John Mood’s portrait that was given to him by another local silversmith, Joseph Brock. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

Often working with his brother, he operated around King and Liberty streets, although they appeared to have moved their shop in that immediate area a few times, as was common. They hung a sign outside with two crossed spoons so customers could easily find them.

The shop appears to have spent much of its time at 302 King St., today an upscale hair salon across from Quiksilver, a beach and surfing-gear store. Then, as now, King Street was a bustling avenue of two- and three-story buildings with shops on the ground level, living quarters above.

In Mood’s time, these businesses needed the skills of enslaved workers — porters, carpenters, mechanics. And some slave owners wanted them to go out and make extra money with their time.

To monitor the system that resulted, Charleston became the lone American city that required those workers to wear slave badges. Only the most entrusted got them.

The freedoms that badges bestowed were so coveted, the punishment for making fake ones was severe. The guilty party “shall be publicly whipped at the discretion of the Court of Wardens, not to exceed thirty-nine lashes, and be put into the stocks, there to remain at least one hour,” the law read.

Each badge bore the year, a unique number and the person’s occupation. Slave owners had to purchase new ones from the city treasurer’s office each year.

When Mood began making them, badges cost $5 for mechanics down to $2 for servants. Those fees raised more than $7,500 for the city. Almost a decade later, in 1844, his badges generated almost $14,000 — or just shy of a half-million in today’s dollars.

On the one hand, the badges marked people as: slave.

Silversmith John Mood made beautiful objects, and slave badges, inside his silversmith shop near the intersection of King and Liberty streets. Today, the area is a popular tourist and shopping district. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

On the other hand, they allowed the same people more freedom to move around the city, ply a trade and sometimes keep a portion of their earnings. It was extremely hard to free enslaved people in South Carolina at the time, so badges provided another option.

While Mood owned several enslaved people, he and his family were deeply committed to the Methodist church, filled with abolitionist thinkers.

In Charleston, those thinkers were not popular. When Mood began teaching the Black worshippers’ Sunday school, he received threats of tarring and feathering.

Meanwhile, at his shop, he continued producing slave badges.

A few years later, he received another request. Several free Black Methodists approached him and his son. Would they be willing to teach at a school for free Black students? Again, Mood agreed.

It launched a long-lasting endeavor as his sons cycled in and out of teaching there while they attended high school and college themselves.

Later, one of his sons applauded the school. “I think we did good and successful teaching and it is a great pleasure to me to know that by our labours in this neglected and at this time despised field of toil our family contributed much to the intellectual and religious welfare of this race.”

Too-la-loo festival

Some of the most important but forgotten places in Charleston linger in restless neglect among those most remembered.

Take White Point Garden, the waterfront destination of picnickers and wedding parties, where tourists snap photographs against a backdrop of finely preserved antebellum mansions. All around them, Confederate monuments describe the war and local heroics.

Who among them knows that Black residents once celebrated so joyfully on this soil?

A year after John Mood died, the Civil War ended, and the people who once wore his badges flocked into the streets. They joined an even larger mass of others who had never known even the freedoms those badges bestowed.

Until now.

Along with about 4 million enslaved people across the crumbling Confederacy, they were free. A couple of months later came July 4, Independence Day.

For almost two centuries, the day had never felt much like freedom to the people robbed of it. But now, thousands of Black people poured through the streets downtown to celebrate the day.

They streamed down King Street past Mood’s silversmith shop, past the Workhouse on Magazine Street, down Broad Street where William Payne once ran his auction house. They sang and laughed down streets where some had been sold at auction.

After the huge crowd congregated at Marion Square, a Black cavalry company began to march. Ten more companies followed, forming a line of 600 men in dark-blue military dress. Several bands filled the hot air with a musical jamboree.

By time they reached The Battery, a good 10,000 people strong, the celebrants filled White Point Garden. The scents of doughnuts, cornbread and ginger beer filled the air. In the harbor’s sparkling waters, which once drew William Rhett back to his wharf, Black boat operators joined the festivities.

And in the crowds, a dance was born. It came to be called the Too-la-loo, which in turn became the namesake of this new annual July Fourth celebration.

After the Civil War’s end, a new kind of Independence Day celebration called the Too-la-loo filled White Point Garden with thousands of formerly enslaved people. Today, it’s a popular hangout spot for locals and tourists alike. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

In 1872, a reporter from the Charleston Courier described the dance: A small group with equal numbers of women and men formed a ring. One female stepped into the center and began sauntering, walking around it, scouting out the gentlemen while the group clapped in time and sang:

Go hunt your lover, Too-la-loo!

Go find your lover, Too-la-loo!

Nice little lover, Too-la-loo!

Oh! I love Too-la-loo!

With that prompting, she selected a man to join her in the center to dance as the group sang. When the two parted, the man began his own quest for a partner. On and on.

The reporter wrote, “At very moderate calculation there were fifty rings performing this dance, in different portions of the Garden, and it was entered into with a zest which kept up the sport from 8 o’clock in the morning until after midnight. By sundown ten hours of the performance had worked up the participants into a moist state of patriotism.”

But the the Too-la-loo soon faded with the promises of Reconstruction.

Whites already were plotting to retake power, tapping an effective union of political maneuvering and white supremacist terror.

Isaiah Doctor’s house

In May of 1919, a little after 7 p.m., Isaiah Doctor was out walking a block away from his Market Street home, an area where mixed-race residential housing met the King Street party district. The 22-year-old Black laborer made his way near Archdale and Beaufain streets.

Two young White sailors headed toward him.

It was a Saturday night, a time when swarms of men on leave from the Navy Yard flocked downtown to the area, known for its poolrooms, bars and other nightlife. Just six months after the end of World War I, the Navy Yard had swelled to 5,000 people.

Doctor approached the enlisted men: an 18-year-old Texan and a 16-year-old from Ohio.

What exactly happened in the seconds when they passed?

Most likely, Doctor didn’t step aside in deference. Some accounts said he jostled the sailors or that he hurled epithets.

Regardless, a chase ensued, and soon a group of sailors arrived at the house Doctor shared with his parents. Someone said he threw rocks at them.

As the ruckus drew attention, a false rumor spread along the streets saying a Black man had killed a White sailor. Enraged sailors and White civilians joined the fray, fuming that Black residents no longer knew their place.

Indeed, after serving in WWI, thousands of African Americans had returned home to the segregated South, where they couldn’t so much as use a Whites-only bathroom. Many challenged the racist system.

Just four years earlier, “The Birth of a Nation” had been released to popular acclaim. President Woodrow Wilson screened the film, adapted from the book “The Clansman,” at the White House.

Now, here was Isaiah Doctor, failing to step off the sidewalk so the White men could pass.

As emotions flared, and a crowd swelled around Doctor’s long, narrow house, Whites broke into two indoor shooting ranges nearby. They stole dozens of firearms and ammunition, then began firing at African Americans in the crowd.

Others headed to Doctor’s house.

During a race riot downtown in 1919, a young man named Isaiah Doctor was shot and killed by White sailors in a yard behind his family’s house at 155 Market St. Today, the spot is part of a large mixed-use development. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

By time police arrived, Chief Joseph Black waded into the tense mob and spotted Doctor in a wide, vacant yard behind his home. He was splayed on his back, a grievous wound to his chest.

Two sailors standing nearby told the chief that Doctor had a pistol, although he did not. In fact, they were his attackers.

As police rushed Doctor to the hospital, thousands of White rioters swamped nearby King Street, ransacking businesses, hauling African Americans into the street, beating some and shooting others. Whites fired into a cobbler shop, hitting the owner’s 13-year-old apprentice, leaving the child paralyzed.

As Doctor died, the White mob killed two other Black men. A third would die a month later.

More than 100 armed Marines streamed into town to regain order.

By then, Roper Hospital filled with casualties, most of them Black. Gunshot wounds, stab wounds, a man bayoneted in the leg.

It was the most destructive episode in Charleston since the Civil War — and an early burst of violence in what became known as the Red Summer, a bloody rash of race riots across America’s cities in 1919.

As Marines and police restored order, Doctor’s family grieved. Their home was a crime scene, one soon forgotten.

Their house is gone today, lost to time and retail development. Instead, the spot is home to an Urban Nirvana, a tenant in the Majestic Square development.

After the riot, however, Doctor’s family had a new voice. Leaders of the Charleston Branch of the NAACP met with the mayor to demand the sailors be held accountable.

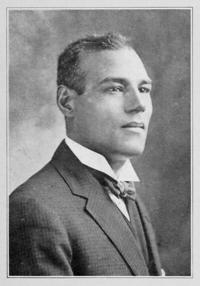

The new group’s president was another young Black man, Edwin Harleston.

Harleston Studio

Harleston had just returned from seeing the world of race and promise beyond the segregated city of his childhood.

After graduating valedictorian of the Avery Normal Institute, he’d studied in Atlanta and Boston. He found a mentor in W.E.B. Du Bois, author and activist, who called him the “leading portrait painter of the race.”

But Harleston faced intense pressure to return home. His father, who’d become wealthy operating a funeral home business, had expansion plans in mind. He wanted his son home working instead of painting up north, where the Harlem Renaissance would soon claim the nation’s attention.

Harleston felt strong ties and responsibility to his family, who moved among the city’s Black elite. They descended from Affra Harleston, who had arrived with that first fleet of English colonists in 1670. Harleston’s father was the child of a White planter and an enslaved woman. His mother had been a free woman of color.

In 1912, Harleston acquiesced. He returned home to become an undertaker.

Eight years later, he married Elise Forrest, among the country’s first Black female photographers, and soon they both worked at the family’s Harleston Funeral Home. It sat on Calhoun Street across and down a few doors from Emanuel AME Church, the post-Civil War incarnation of the African Church.

Soon, the couple opened Harleston Studio in a white three-story single house at 118 Calhoun St., where they also lived. It stood right next door to Emanuel. Although the funeral home’s building still stands, the studio does not. Today, the edge of Citadel Square Baptist Church’s parking lot covers the space.

The studio gave the Harlestons a sanctuary for their artistic dreams, if only when they weren’t working at the funeral home. The rooms filled with the scent of paints and dark room chemicals, and the sounds of people. The Harlestons set aside part of the building to provide Black residents their first public art gallery, which featured their work.

From inside, behind a giant camera, Elise pursued her photography. Edwin, known as “Teddy,” donned a smock and parked himself in front of easels to paint portraits of Black subjects showing a nuance and humanity that challenged caricatures of the time. A nurse with worried eyes. A solemn minister in a dark suit, a red-bound Bible in his lap. A woman in a soft lilac dress, carrying baskets of wares past blooming wisteria vines.

Harleston Studio stood on Calhoun Street beside Emanuel AME Church. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

As he toiled, local White artists prospered with the rise of the Charleston Renaissance. Among them, Dorothy and DuBose Heyward found “Porgy and Bess” fame. A writer named Julia Peterkin, great-granddaughter of silversmith John Mood, became the first Southern author to win a Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

Their work reintroduced the old Holy City, in all her antebellum allure, to a national audience.

But at the time, the Charleston Renaissance was a Whites-only affair. When Harleston went to Magnolia Plantation and Gardens to paint the landscape himself, he had to dress like a workman to get in, then hide while painting. Black guests weren’t allowed.

In 1926, the city’s mayor and the Charleston Museum’s director approached him with a life-changing offer. They wanted to exhibit his work there.

Not long after, they backed out. Whites feared crowds of African Americans descending on the museum.

Harleston still became the most famous Black portrait painter of his day. Sometimes, he used Elise’s photographs for inspiration, as he did in 1930 to paint a renowned author and activist.

Sue Bailey Thurman, then the traveling secretary for the national YWCA, stayed at the Harlestons’ home during a national tour. Segregation laws barred her, and all other Black visitors, from lodging in Charleston’s public hotels

Hotel James

Two decades later, in 1952, an Evening Post headline announced: “Hotel For Negroes to be Dedicated Here Tomorrow.”

The modern space on Spring Street promised 20 guest rooms, hot and cold water, steam heating, a bar, and a large ballroom that could double as a convention hall.

Black visitors not only had a place to stay but also gather for big fun.

It was a time when they had little access to places like the Charleston Museum or the Gibbes Museum of Art. Most of the area’s beautiful beaches — Isle of Palms, Sullivan’s Island and Folly Beach — all banned them. Local theaters restricted them to the balconies.

Spring Street, however, had become the center of Black commerce downtown.

The four Washington brothers who opened Hotel James already ran the largest Black-owned restaurant in town next door, the Ashley Grill. Civil rights activist Esau Jenkins owned the J and P Cafe on the same block. Next door, the Birdland nightclub offered another option.

Now, a good time on a larger scale could be found at the Hotel James.

Hotel James opened in 1952 on Spring Street, offering Black travelers and performers a hub of entertainment. The building is gone now, replaced by a McDonald’s. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

Decked out in dark suits and Fedoras, crowds swelled beneath the brick hotel’s second-story neon sign. Drivers idled outside in their 1940s-era Oldsmobiles and Cadillacs. Music thumped through the windows.

Titans of entertainment arrived: Fats Domino, Duke Ellington, Count Basie and James Brown.

But it wasn’t just a nightspot. As headlines filled with a high-profile court case, four Black jurors stayed at the hotel. (White ones were housed at a different hotel.)

The Negro Shriners held ceremonies there. Piano students performed. One year, 400 Black funeral home directors and embalmers held their conference at the hotel.

It was among the few Charleston spots repeatedly included in the Green Book, which listed places across the country where African American travelers could eat or stay in peace.

Over the coming decades, slowly, integration came.

As activists and the federal courts forced open the doors of White-only businesses, more choices drew customers away from Hotel James. Along with many other Black-owned businesses, it closed after two decades in business.

In 1973, an Evening Post story announced that the hotel, along with other properties on Spring Street and Hagood, would be demolished, paving the way for a $50 million Ashley River development.

By then, the six-lane Crosstown had bisected the surrounding Black community. The booming medical district encroached. Charleston’s peninsula had begun a ceaseless march into gentrification.

Hotel James is gone now. A McDonald’s sits on the site, dense urban traffic whizzing by.

Customers in the parking lot can almost see the glittering Ashley River beyond, where a fleet of English colonists, including Affra Harleston, plied its currents 350 years ago with the first enslaved people on board.

Today, as the fast-food patrons order their Big Macs, they can’t actually see the water so close to them.

A new high rise, part of the WestEdge waterfront development, blocks the view. And memories of places like Hotel James vanish with the smell of each new warm batch of French fries carted away into the bustle.

Around 1696, Col. William Rhett steered home to his wharf, then in the area that is now Riley Waterfront Park, with 165 enslaved Africans on board. Hundreds of slave ships would follow. Gavin McIntyre/ Staff

Contact Jennifer Hawes at 843-937-5563. Follow her on Twitter @jenberryhawes.