For the inaugural event, historians recalled the siege of Fort Motte, assisted by Rebecca Brewton Motte

FORT MOTTE — When Patriot officers told Rebecca Brewton Motte on May 12, 1781, they needed to set fire to her house — which British soldiers had turned into a supply depot — she gave them the arrows to do so, historian Peggy Pickett told about two dozen history buffs, neighbors and scholars gathered this week at the site.

Motte’s story 244 years ago was the focus of the South Carolina American Revolution Sestercentennial Commission’s inaugural Founding Mothers event.

Members of the commission, which goes by SC250 for short, hope to create an annual tradition of recognizing the women who contributed to America’s founding as the country enters its 250th year.

Luther and Doraine Wannamaker, who own the property about 40 miles south of Columbia that once included the Motte home, offered to host the first Founding Mothers event on the anniversary of the day the British surrendered the fort. That just so happened to be the day after Mother’s Day.

Gov. Henry McMaster proclaimed Monday to be Founding Mothers’ Day.

Gov. Henry McMaster proclaimed Monday to be Founding Mothers’ Day.

Commissioners are aiming higher: They want state law changed to designate Founding Mothers’ Day as the Monday after Mother’s Day every year.

They have the backing of at least one legislator, Sen. Jeff Zell, a Sumter Republican who said Monday he’d be interested in sponsoring a resolution when legislators return to Columbia next year.

Putting the day in state law would be a permanent recognition of the role women played in The Revolution, a role that often gets overlooked, said retired Gen. Will Grimsley, chairman of the SC250 commission.

“We need to constantly go back and tell everybody’s story,” Grimsley said. “But a really undertold part of the story, quite frankly, are women.”

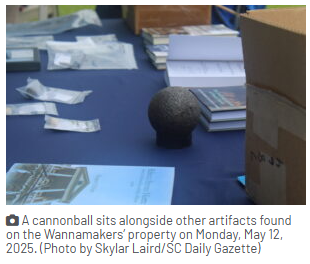

The Wannamakers have done reenactments of the siege, with men on horses riding from what would have been Fort Motte to the farmhouse (where Motte herself had been exiled) to tell her their plan of laying siege to her home, said Doraine Wannamaker. The family hosts private tours of the spot, showing off the stone marker where the house once stood. An archaeologist from the University of South Carolina has visited repeatedly to dig up artifacts, including a cannonball and shot used by the British and Patriots.

But Monday was the first official event the Wannamakers have hosted alongside the commission responsible for highlighting South Carolina’s role in the Revolutionary War.

The story of Fort Motte

By the time British troops reached Motte’s home in what is now Calhoun County, on a bluff that overlooks what is now Congaree National Park, she had already been forced out of one home because of the war.

Motte’s original home in Charleston was selected as a headquarters for Loyalist lieutenant colonels and their company of 30 soldiers when British troops captured the coastal city. Motte, widowed not long before, fled inland to the property once owned by her brother, who had died several years earlier, according to the American Battlefield Trust.

Only a couple of months after Motte moved into the house, the British again came for her home. The house, located near the Congaree and Wateree rivers, was an ideal location for supplies coming from Charleston and headed to Camden and Ninety-Six, said Pickett, who has researched women’s contributions to the war effort.

In January 1781, British troops, led by Lt. Donald McPherson, took over the house, called it Fort Motte and surrounded it with fortifications. Motte and her three children fled to a nearby farmhouse on the property, according to the American Battlefield Trust.

Patriot forces took interest in Fort Motte in May of that year, after taking out several other British posts.

Forcing the British to surrender Motte’s house would take out a crucial supply line for the British.

As the Patriots, led by Brig. Gen. Francis Marion — known as the “Swamp Fox” — began the siege on Fort Motte, McPherson refused to surrender, correctly guessing reinforcements were approaching, Pickett said.

It was then that Motte, approached by either Marion or Lt. Colonel Henry Lee, agreed to let the Patriots burn down her house and destroy the supply depot altogether. According to some historical accounts, Motte gave the Americans combustible arrows to help them.

“Instead of being upset when told, she replied, according to Lee’s memoirs, that she was grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the good of her country, and she would watch the approaching scene with delight,” Pickett said.

After setting fire to the house’s roof, the Patriots fired grapeshot at any British soldiers who tried to put it out. McPherson surrendered, and the Patriots took back the burned Fort Motte. Patriots and British officers then dined together in the farmhouse where Motte and her family had been staying, Pickett said.

(The scene outside wasn’t so pleasant. Three Loyalist prisoners were ordered hanged while the officers dined, which angered Marion, according to American Battlefield Trust.)

“Now, the capture of Fort Motte was not a grand, epic battle,” Pickett said. “It was a small, relatively bloodless engagement, but it was a significant victory for the Americans because it changed the momentum of the war in their favor.”

Not much remains of the site of the siege.

A large stone that shows where the house once stood reads, “Site of Rebecca Motte’s home, sacrificed for her country, May 12, 1781.” As historians told the story of the battle, flags waved in blustery wind behind them, one British and several representing the Patriots, including the Gadsden (“Don’t Tread On Me”) flag.

Women during the war

Most women’s contributions to the war were small but meaningful. They managed farms and plantations while their husbands and sons were fighting in the war, sent food and provisions to the army and gathered information to pass along. They took sick and wounded soldiers into their homes and either nursed them back to health or buried them when they died, Pickett said.

“None of these things were very easy for them to do,” Pickett said.

Others had more active roles in thwarting British troops and helping the Patriots claim victory.

Take, for instance, Dorothy Sinkler Richardson, who historians credit with saving Marion’s life in 1780.

When British Col. Banastre Tarleton set up a decoy campsite near Richardson’s plantation meant to lure Marion for an attack, Richardson sent a messenger to warn Marion, according to SC250.

“Thanks to Dorothy Sinkler Richardson, Francis Marion remained at liberty to continue to make life difficult for the British,” Pickett said.

Jane Thomas, who lived in what is now Spartanburg, similarly foiled a plot to surprise American troops after overhearing two women talking about a plot to surprise Patriot soldiers near Thomas’ house. Thomas, who was 60 miles from home, rode back straight away to warn the men, allowing them to instead surprise the British troops, Pickett said.

Emily Geiger, at 18 years old, volunteered to deliver a message to Gen. Thomas Sumter (“The Gamecock”) to meet Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, believing a young woman would be able to get through enemy lines where a m an would not. She was successful and helped join the two battalions, Pickett said.

an would not. She was successful and helped join the two battalions, Pickett said.

In coming years, the commission plans to host similar events in other parts of the state, highlighting the stories of different women, said Molly Fortune, executive director of SC250.

Telling these stories is a major step forward, but there’s more work to be done, Pickett said.

Designating a day to remember the ways in which women contributed to the country’s foundation is a way of ensuring their stories remain in the public eye instead of being lost to history, she said.

“We are just beginning to explore the activities performed by Native American women and women of African descent,” Pickett said. “We need to do the research to bring their stories to light, because the more stories we bring to light, the more attention we bring to the important role that South Carolina played in winning our independence.”

–scdailygazette.com