Fort Donelson has “Unconditional Surrender” Grant. It has an early morning Confederate attack, a breakout by Nathan Bedford Forrest and, in short, the stuff that makes good history. But from this outsider’s perspective looking in on the Western Theater, I believe (and have believed for some time) that Fort Henry, in the grand scheme of things, gets the proverbial short end of the stick.

No, it does not last as long as the operations at Fort Donelson. It does not have the casualties that Donelson witnesses. It does, however, have an impact on Confederate strategy. In fact, the Confederacy repeatedly fell back on that strategy throughout the remainder of the war.

At the war’s onset, Commander in Chief of the Confederate States of America Jefferson Davis and his subordinates settled on the idea of defending all borders of the fledgling nation, which encompassed 750,000 square miles of territory. Historian James McPherson calls this plan the “dispersed defense.” Early in the war, this strategy won political points for Davis and his administration by protecting many points on the periphery of the Confederacy. However, it also made things difficult for the Southern commanders vainly attempting to hold vast swaths of land with minimal manpower. Fort Henry’s fall on February 6, 1862, changed all of that.

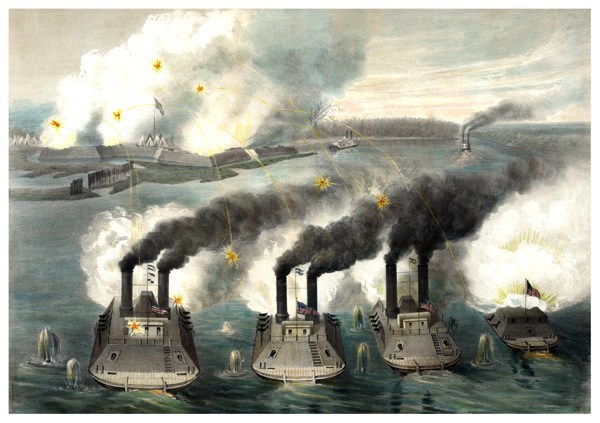

The capture of Fort Henry by Union forces opened much of the Tennessee River and its banks to Northern soldiers. Demonstrating the river’s dagger-like course through the heart of western Tennessee, a cadre of Federal gunboats proceeded along the river in the wake of Fort Henry’s fall all the way into northern Mississippi and Alabama. While the raid ultimately failed to destroy several larger objectives, it none the less proved the Northern hypothesis that the Confederacy was a hollow shell–crack its outer layer and nothing lay in the interior to stop Federal advances.

On February 8, Jefferson Davis began veering the Confederacy away from its dispersed defense. Davis could no longer cave to political pressures while Union forces carved up the Confederacy’s boundary. Accordingly, he ordered Southern soldiers to make their way to Tennessee. Mansfield Lovell’s soldiers began their trek from New Orleans while Braxton Bragg left Pensacola en route for the Volunteer State. Confederate gunboats protecting New Orleans also sailed up the Mississippi River, eventually exposing the Crescent City to Union hands.

While stripping the Confederacy of its exterior defenses, forces began to concentrate in northern Mississippi, poised to strike back the Federal thrust through western Tennessee. It was a new take on Southern strategy, gathering forces at select points to attack the enemy when advantage seemed in the Rebels’ favor. The Confederacy altered its strategy to the offensive-defensive as a way to preserve, as best as it could, the exterior of its hollow shell. This strategy manifested itself first at Shiloh in early April 1862 and later at places like Antietam, Perryville, and Gettysburg.

One small fort on the Tennessee River and its capture by the forces of Ulysses S. Grant and Andrew Foote in February 1862 changed the shape, but not the course, of the Civil War for the next three years.

–emergingcivilwar.com