America’s Civil War ended when Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse in Virginia on April 9, 1865, but President Abraham Lincoln had planned for it to end symbolically a few days later.

Lincoln wrote letters to organize a special April 14 ceremony at the same place where the war had begun four years earlier — at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. Union Maj. Robert Anderson, who had surrendered the fort in 1861 after Confederate forces opened fire, would return and raise the same flag he had furled.

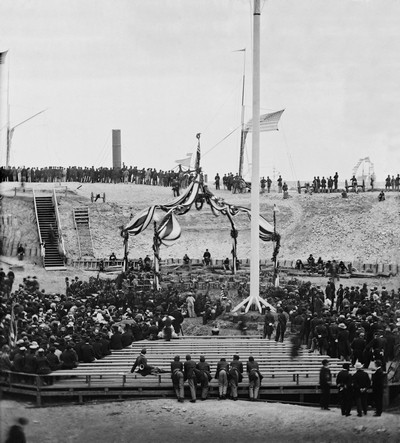

This photograph shows the crowd inside Fort Sumter on April 14, 1865, moments before the United States flag was raised there, symbolically marking the Civil War’s end. Library of Congress

But this symbolic gesture would be largely lost to history. On the same day as the ceremony, Lincoln attended a play in Washington, was shot, and died the next day.

“If Lincoln had lived, every textbook in American history would have shown the flag raising at Fort Sumter as the conclusion of the war,” Charleston lawyer and historian Robert Rosen said. “That’s what it was meant to be.”

As the 150th anniversary of this historic event approaches, the Lowcountry is planning to mark the occasion much like it marked the same anniversary of the war’s start — with a series of lectures, concerns and somber events designed to raise awareness of a pivotal point in the nation’s history and to remember its vast impact on so many lives.

The highlight will be a series of free lectures by some of the nation’s leading historians.

Bo Moore, dean of The Citadel’s School of Humanities, said the morning lectures will focus on the war’s legacy, while the afternoon sessions will explore the war as Americans have chosen to commemorate it.

“There’s no serious disagreement that the Civil War, the issues that produced it and the way in which they were addressed during and after the war, go to the heart of the American experience, what we were, what we are, what we hope to be,” he said.

Moore said the 90-minute sessions will not only include lectures but also a larger discussion with the audience. “If we’re lucky, in some small way, we might promote some narrowing between professional understanding and public understanding of the conflict,” he said.

Tim Stone, superintendent of the Fort Sumter National Monument, said most associate the fort with the war’s beginning, but it also played a symbolic role at the end. Some of Lincoln’s letters regarding the flag re-raising there currently are on display at the National Park Service’s Fort Sumter Visitors Center on Liberty Square.

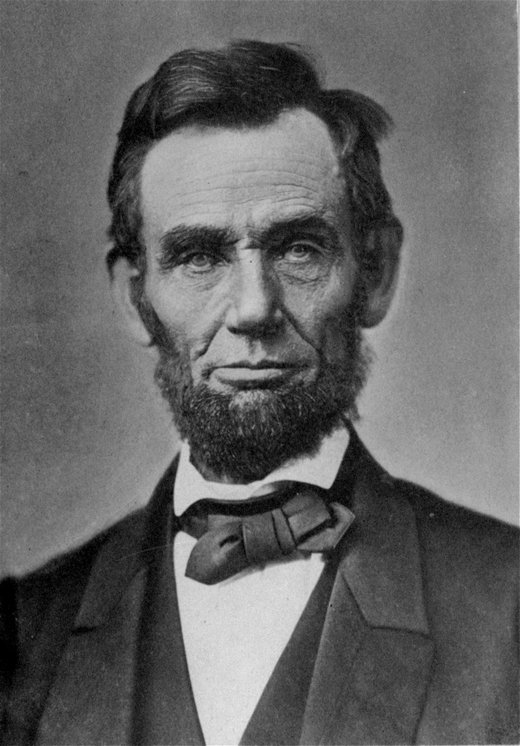

President Abraham Lincoln was shot the same day, April 14, 1865, that a ceremonial flag-raising took place at Fort Sumter to recognize the end of the Civil War. Lincoln died the next day. AP

“In our time, it’s hard to look back and remember how significant that was,” Stone said. “It would have been a climactic event of the Civil War had it not been for Lincoln’s being assassinated that evening. This event was lost to that — it was overwhelmed by it.”

So the visitor center exhibit, which will remain until the fall, also includes a bloodstained piece of linen scavenged from the Petersen House, where Lincoln was taken after being shot. It’s one of several objects on loan from the Ford’s Theatre National Historic Site.

The Charleston of April 1865 was a dramatically different place. The last Confederate forces had withdrawn from the city in mid-February, and the city’s newly liberated black population already had organized a few large parades. Union troops occupied the city streets, which were still in ruins from an 1861 fire and more than a year of steady shelling.

Rosen said the flag re-raising ceremony drew William Lloyd Garrison, the nation’s leading abolitionists and one of the most despised men in Charleston. Others attending included Henry Ward Beecher, whose sister wrote “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”; Robert Smalls, whose 1862 theft of the CSS Planter had dealt the Confederacy one of its first big setbacks in the Lowcountry; and the son of Denmark Vesey, who was put to death for organizing a slave revolt in 1822.

After the war, Garrison was greeted warmly by the city’s black population and delivered a speech in which he said, “I have been an outlaw, with a price set upon my head for 30 years for your sake, but I never expected to look you in the face or that you would ever hear of anything I might do on your behalf.”

The lingering issues of racial inequality in America — seen most recently in the unrest in Ferguson, Mo. — make the Civil War anniversary uncomfortable for some.

“Race and racism and racial issues are a central theme in American history, unfortunately,” Rosen said. “We have to address them and get them out on the table and talk about them. And there’s a lot to talk about,”

While most Americans say the Civil War had a profound impact on the nation, there are often equally profound differences in their understanding of what the impact was, Moore said.

“The Civil War is really a revolution,” Rosen said. “It’s a great time of jubilation and celebration for the black community, but among a great majority of white people, it’s a time of utter catastrophe. There is a huge racial divide about this.”

Ultimately, organizers said they hope the upcoming commemoration underscores how the larger forces behind the Civil War are relevant to the nation’s present — and its future.

“Some of the central issues in the American experience, some of its most noble and ignoble impulses, come to a head, a most dramatic head, during our experience in the Civil War,” Moore said. “That’s not to say they’re over. They continue, but that’s the crucible, and it provides the best single point in the nation’s past to talk about and understand some of these issues in American life.”

-Robert Behre, postandcourier.com

###