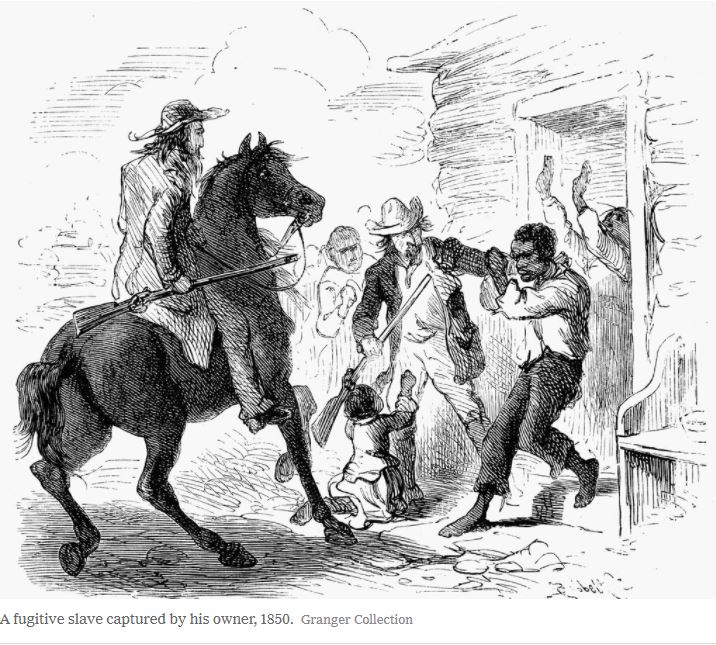

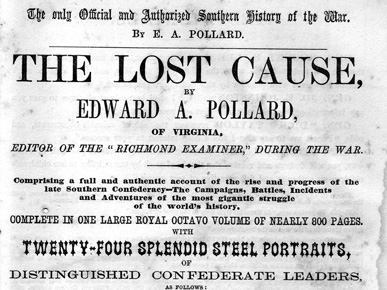

He had tried, and failed, once before. In 1859, the Virginian Edward Alfred Pollard, a journalist and Southern partisan, had published a defense of slavery, “Black Diamonds Gathered in the Darkey Homes of the South.” Then came the election of Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War, the Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment, which abolished the system of slavery Pollard had hoped to preserve. After the Confederate surrender at Appomattox in April 1865, he turned to a new project, publishing, in 1866, a book titled THE LOST CAUSE: A NEW SOUTHERN HISTORY OF THE WAR OF THE CONFEDERATES.

This effort would succeed where the first had fallen short. Pollard’s framing of the “Lost Cause” was to long endure, and it’s safe to say that no other American title of 1866 is shaping the nation in the way Pollard’s is even now. “No one can read aright the history of America,” Pollard wrote, “unless in the light of a North and a South.” For all its bloodshed, he argued, the Civil War “did not decide negro equality; it did not decide negro suffrage; it did not decide State Rights. … And these things which the war did not decide, the Southern people will still cling to, still claim and still assert them in their rights and views.”

Here, then, was the ur-text of the Lost Cause, of the mythology of a South that believed its pro-slavery war aims were just, its fate tragic and its white-supremacist worldview worth defending. In our own time, the debates over Confederate memorials and the resistance in many quarters of white America, especially in the South, to address slavery, segregation and systemic racism can in part be understood by encounters with the literature of the Lost Cause and the history of the way many white Americans have chosen to see the Civil War and its aftermath.

To Pollard, the Southern side had fought nobly for noble ends. “The war has left the South its own memories, its own heroes, its own tears, its own dead,” he wrote. “Under these traditions, sons will grow to manhood, and lessons sink deep that are learned from the lips of widowed mothers.” Pollard declared that a “‘war of ideas,’” a new war that “the South wants and insists upon perpetrating,” was now unfolding.

And in many ways it unfolds still. The defiance of federal will from Reconstruction to our own day, the insistence on states’ rights in the face of the quest for racial justice and the revanchist reverence for Confederate emblems and figures are illuminated by engaging with the ethos of which Pollard so effectively wrote.

He enlarged on his thesis in “The Lost Cause Regained,” published in 1868. Pollard wrote that he was “profoundly convinced that the true cause fought for in the late war has not been ‘lost’ immeasurably or irrevocably, but is yet in a condition to be ‘regained’ by the South on ultimate issues of the political contest.” The issue was no longer slavery, but white supremacy, which Pollard described as the “true cause of the war” and the “true hope of the South.”

The Civil War, then, was to be fought perennially. Defeats on the battlefield as well as the trials of the early Reconstruction period were cast as Christlike tribulations that would lead to a resurrection of the old order. The South, Pollard wrote, “must wear the crown of thorns before she can assume that of victory.”

As the decades after the war went by, that post-bellum victory seemed assured. In his essential book RACE AND REUNION: THE CIVIL WAR IN AMERICAN MEMORY, David W. Blight detailed how a white narrative of the war took hold, North and South, after Appomattox. As early as 1874 the historian William Wells Brown had said, “There is a feeling all over this country that the Negro has got about as much as he ought to have.” Slavery and race were thus pushed to the side in favor of a more comforting story of how valiant brother had taken up arms against valiant brother.

In this recasting of reality, the Civil War was a family quarrel in which both sides were doing the best they could according to their lights. Right and wrong did not enter into it. White Americans chose to celebrate one another without reference to the actual causes and implications of the war.

“The memory of slavery, emancipation and the 14th and 15th Amendments never fit well into a developing narrative in which the Old and New South were romanticized and welcomed back to a new nationalism,” Blight wrote, “and in which devotion alone made everyone right, and no one truly wrong, in the remembered Civil War.” To recall that the war had been about what Lincoln had called a “new birth of freedom” meant acknowledging the nation’s failings on race. So white Americans decided to recall something else.

Blight quoted a 1912 novel, “Cease Firing,” by the Southern author Mary Johnston. In the book’s closing pages, a Confederate soldier observes, “I think that we were both right and both wrong.” In such a view, it had all been a struggle between two reasonable parties over the nature of the Constitution; slavery was incidental.

By minimizing race in the story of the war, white Americans felt free to minimize race not only in the past but in the present — leading, as Blight wrote, to “the denigration of Black dignity and the attempted erasure of emancipation from the national narrative of what the war had been about.”

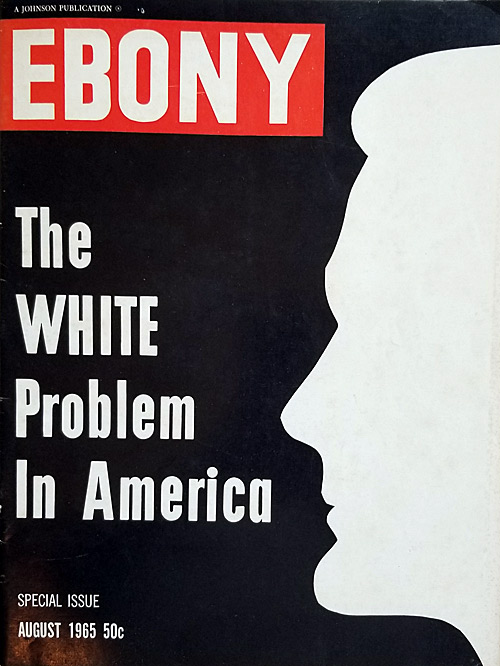

Yet the war, and much of the history of the nation before and after, had been about race. A century after Appomattox, in 1965, at a time when white Southerners were still deeply engaged in preserving Pollard’s Lost Cause, the editors of Ebony magazine published a special edition that became a book: THE WHITE PROBLEM IN AMERICA.

“The problem of race in America, insofar as that problem is related to packets of melanin in men’s skins, is a white problem,” not a Black one, Lerone Bennett Jr., a historian and senior editor at Ebony, wrote in the volume’s opening essay. “And in order to solve that problem we must seek its source, not in the Negro but in the white American (in the process by which he was educated, in the needs and complexes he expresses through racism) and in the structure of the white community (in the power arrangements and the illicit uses of racism in the scramble for scarce values: power, prestige, income).”

Contributors included Bennett, James Baldwin, John O. Killens, Whitney Young, Carl T. Rowan, Louis E. Lomax, Kenneth B. Clark and Martin Luther King Jr. King’s piece, “The Un-Christian Christian,” argued that white religious believers “too often … have responded to Christ emotionally, but they have not responded to His teachings morally.” As in the Lost Cause of the South and the reunion narrative of the whole nation, white Christianity of midcentury America chose the comforting elements of history and theology rather than the uncomfortable ones.

Baldwin closes the book by imagining the interior monologue of the white American who has been raised on the false history of the Lost Cause. “Do not blame me,” Baldwin wrote of the white “stammering” in his conscience. “I was not there. I did not do it. My history has nothing to do with Europe or the slave trade. Anyway, it was your chiefs who sold you to me. … But, on the same day … in the most private chamber of his heart always, he, the white man, remains proud of that history for which he does not wish to pay, and from which, materially, he has profited so much” — a history manipulated to make the unspeakable palatable.

“A man is a man,” Baldwin wrote, “a woman is a woman, and a child is a child. To deny these facts is to open the doors on a chaos deeper and deadlier, and … more timeless, more eternal, than the medieval vision of Hell.” Only when Pollard’s Lost Cause is truly lost will the nation escape those flames, and begin at last to glimpse the light.

Jon Meacham is the author, most recently, of “His Truth Is Marching On: John Lewis and the Power of Hope.