VIRGINIA: Williamsburg’s Civil War History Resurfaces

The Battle of Williamsburg gets lost in the shuffle of history.

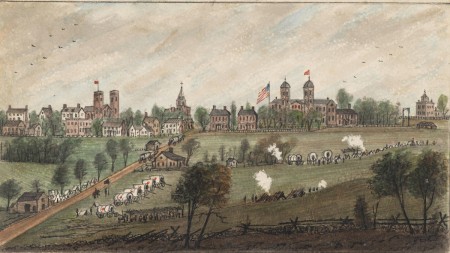

Drawn by a Union army cartographer, this August 18, 1862 view of Williamsburg shows the temporary headquarters of the Army of the Potomac’s III Corps just 3 weeks before soldiers of the 5th Pennsylvania Cavalry burned the Wren Building, shown at center right, in the aftermath of a Confederate raid on the town.

Not only does it get less emphasis among Civil War historians, it also gets lost amid the city’s own storied history, according to historian and author Carson Hudson, who gave an illustrated lecture Friday evening to about 100 people at the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg.

And good luck finding the battlefield where it took place on May 5, 1862. Little of it is preserved and accessible to the public.

The battle began as Brigadier General Joseph Hooker’s Union division attacked the Confederate rearguard at Fort Magruder, an earthen fortification along the Williamsburg Road.

That site, now just off of Penniman Road, is about a mile southeast of the restored Colonial Williamsburg. The Confederates had retreated from Yorktown, and would subsequently retreat to Richmond after the daylong rainy battle.

“The battlefield itself hasn’t survived very well, unlike other places where you have national parks,” Hudson said. “Colonial Williamsburg is kind of a mixed blessing.”

Hudson explained that when Colonial Williamsburg was formed, the town was frozen in time due to the 88 buildings dating to the 18th and 19th centuries which were saved.

“But because Colonial Williamsburg came in, the emphasis was on Colonial history and not Civil War history, and it’s kind of a shame,” Hudson said, “because to be quite honest with you, after working in this area for many years, I can tell you five times as many Civil War stories about the town as I can tell Revolutionary War stories about George Washington.”

Hudson said with Jamestown, Yorktown and Colonial Williamsburg, most people other than Civil War buffs come to the region with an idea only of its Colonial history.

A number of those familiar with Civil War history happened to be in the audience. When Hudson asked about a specific slide in his lecture, there was someone ready to identify it accurately.

Others, however, like Denise Goode of Toano, knew less about the significance of the battle.

“I didn’t really realize Williamsburg was involved in the Civil War like it was,” Goode said. “Other Civil War battles I heard more about than Williamsburg. There were so many bigger ones in Virginia.”

Hudson said the battlefield virtually disappeared because no one cared about it, with building commencing on the wheat fields around the town, which was in bad shape after the battle and after the Union Army occupied Williamsburg during the war. It was rebuilt as a late Victorian town and, later, electricity and paved streets came along.

“With the history of Williamsburg, you have a series of different towns from decade to decade,” Hudson said.

While there were about 4,000 casualties among Confederate and Union troops during the battle, that gets overshadowed by bigger battles such as Gettysburg. However, Hudson said the daylong, rainy battle remains important because it prepared those soldiers for that calamitous fight in Pennsylvania.

Chuck Hassett of Williamsburg said Hudson’s presentation was a useful refresher for him.

“I’m not sure I learned a whole lot new because I’ve read a lot on the subject, but it brought it home so much for me being here,” Hassett said.

–vagazette.com

###

SOUTH CAROLINA: Confederate Flag Will Not Reappear in Courtroom

YORK — A version of the Confederate Battle Flag had flown for decades inside the main courtroom of the York County Courthouse in York. It stood among five other historic flags. Pictures of Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson hung behind the judge’s bench.

No more.

The Confederate flag and pictures of Confederate Civil War generals Stonewall Jackson, left, and Robert E. Lee, are in storage and will not be put back in the renovated York County Courthouse’s main courtroom. Andrew Dys

The courtroom will re-open Sunday as part of a $10 million courthouse renovation. But that historic courtroom will not have a Confederate flag or those pictures, York County Clerk of Court David Hamilton has decided.

Hamilton, as clerk, has authority over county courthouse buildings. He recently said he has a deep and strong understanding of York County history, but decided those items were part of an old era in the historic courthouse. But a new era will not include the flag or pictures, Hamilton said.

“It is a different time,” Hamilton said. “When we looked at the historical items that included Civil War era items. This is a new era and time, and it is time to move on.”

The York County Courthouse, closed since 2011 for renovations, was built in 1914. Other historical items, including retired judges portraits, will go back in the courtroom along with the United States flag and South Carolina state flag, Hamilton said.

The Moss Justice Center in York, where criminal court has been held for two decades, has no Confederate flag in its courtrooms. The probate court and family court and master in equity courts don’t either. Magistrate courts do not have Confederate flags.

Hamilton’s decision has earned praise from both political parties and county and legal and community leaders.

Kevin Brackett, 16th Circuit Solicitor, recalled that as a young prosecutor in the early 1990s he had a case where the defense lawyer for a black defendant vehemently objected to the Confederate flag in the rear of the courtroom and the pictures behind the judge. The defendant and lawyer asked the judge that the items be removed, or that the trial be moved to a different courtroom.

“It was an issue, the flag and the pictures in the courtroom, that was raised in court,” Brackett said. “It became a distraction.”

Longtime defense lawyers Tom McKinney and Harry Dest, 16th Circuit Public Defender, who both have tried cases in the courtroom, agreed with Hamilton’s decision.

“There is no place in a court of law, a place of justice for all, for the Confederate flag,” McKinney said.

Lawyer Montrio Belton, treasurer of the York County Bar Association, said not putting the flag and pictures back up is the right and wise move.

“A courtroom is meant to provide justice for everyone equally,” Belton said. “The halls of justice mean everyone is equal. But the Confederate flag in a courtroom says something to people of color, that some way they might be disenfranchised.”

State Rep. John King, D- Rock Hill and the leader of the S.C. General Assembly Black Caucus, praised Hamilton’s decision. Longtime York lawyer Jim Bradford, who was part of a group that pushed for the York courthouse to be restored with dignity and historic integrity, also agreed.

The Confederate flag has been and remains a divisive symbol for millions of people. Outgoing Gov. Nikki Haley pushed for the flag outside the S.C. Statehouse to come down in 2015 after nine black people were killed by white supremacist Dylann Roof. In her state of the state address earlier this month, Haley called the Confederate flag, “a divisive symbol of an oppressive past.”

Hamilton sought legal advice to make sure his decision did not run afoul of South Carolina’s Heritage Act. That state law bars changes to monuments and historic buildings without legislative action. Hamilton determined after getting legal advice that the best solution is to research the history of the particular flags that flew in the county courthouse, which Hamilton has been told flew over York County at different times in its history, then possibly put them in a display area at the renovated courthouse.

It is unclear exactly how long the flag and the pictures of Confederate generals were on the walls of the courtroom before renovations. It is even unclear who put the flags and pictures up, Hamilton said. The items have been stored at the McCelvey Center in York since renovations began.

The courtroom must ensure that all who enter it believe they are treated equally, Hamilton said. Lady Justice, the emblem of courts, has a woman with scales and blindfold.

–theherald.com

###