VIRGINIA: Law Allows For Expansion of Historic Civil War Battlefield

PETERSBURGv, a. — Virginia’s Petersburg National Battlefield, a climactic site in the collapse of the Confederacy in the Civil War, has been cleared for a huge expansion under a new law that would authorize it to become the nation’s largest protected battlefield.

The park commemorates sites in the war’s longest battlefield conflict, marked by bursts of bloody trench warfare spanning some ten months between 1864 and 1865. Legislation signed days ago by President Barack Obama authorizes, but does not pay for, the addition of more than 7,000 acres to the existing 2,700 acres of rolling hills, earthworks and siege lines already under protection at Petersburg.

Expansion has been a longtime priority of park advocates and comes amid a push to bolster and protect battlefields around the country this decade as the nation marked the 150th anniversary of the war. Supporters say the larger boundary would not only protect historic sites from commercial development but also give park visitors a more comprehensive understanding of the Petersburg campaign, which left tens of thousands of men dead.

“We’re finally moving forward. … We’re looking at the park and looking at the story in a whole new way,” said Lewis Rogers, the park’s superintendent, who joked that the weeks of waiting for the president’s signature had left him in misery.

Miles south of the former Confederate capital of Richmond, the Petersburg area became the crucible of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s 10-month Union siege that broke the back of the Confederacy and precipitated the surrender of the South’s Gen. Robert E. Lee at Appomattox, Virginia.

Grant prized Petersburg, with its rail connections, as key to taking Richmond. But Lee’s forces dashed any Union hopes of swiftly seizing the gateway city. In July 1864, the Union detonated powerful explosives beneath a Confederate line, creating an enormous blast crater, but the ensuing Union attack failed, and it wasn’t until April 1865 that the Union finally smashed through.

The park draws about 200,000 visitors a year according to National Park Service figures, far fewer than such higher-profile sites as Gettysburg in Pennsylvania, with more than 1 million tourists annually. Still, the Petersburg park is key to the area economy, bringing in some $10 million a year, and officials hope expanding the battlefield’s protected footprint would reap even more visitors.

Although the legislation, which was included in a defense policy bill Congress passed in recent weeks, would not include any new funding, some land is already in the hands of preservation groups that plan to transfer it to the National Park Service.

“Our goal is to create a seamless visitor experience so that they can see the story from start to finish,” said Jim Campi, a spokesman for the Civil War Trust, which owns about 1,800 acres of boundary expansion land.

Among the new properties the park could acquire is about 5,000 acres in Dinwiddie County where several decisive battles took place, Rogers said. Battlefields that would benefit include Five Forks, known as the “Waterloo of the Confederacy,” and the Petersburg Breakthrough, where the advancing Union Army forced Lee to urge the Confederate government to evacuate Richmond.

Rogers said the first priority will be acquiring property that is privately owned and most vulnerable to commercial development that could endanger battle sites.

As for the funding, “the word there is creativity,” Rogers said.

The possible changes come as the city of Petersburg, now grappling with nearly $19 million in unpaid obligations, could sorely use an influx of cash. City workers’ pay has been cut and firefighting equipment repossessed as part of the financial difficulties.

Rogers acknowledged that changes could take years but said preserving the land and telling the soldiers’ stories is worth the effort.

“There’s something … spiritual about that,” he said. “Something people find very compelling. There’s something about standing on the ground where something happened and understanding with clarity what happened that gives you a special connection.”

–abcnews.go.com

###

MISSOURI: Civil War in Missouri Teaches Lessons About Guerrilla Fighting

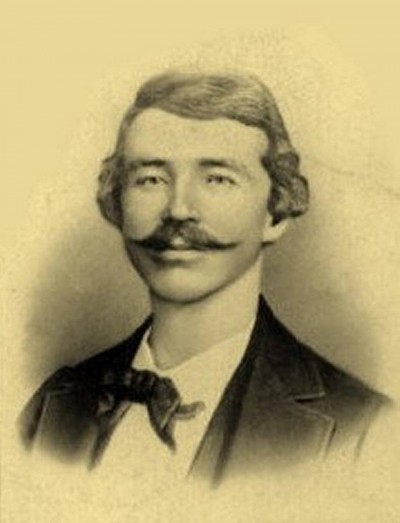

On Aug. 21, 1863, William Clarke Quantrill and several hundred Missouri bushwhackers rode into the abolitionist stronghold of Lawrence. Hell had come to breakfast. Quantrill’s men burned huge swaths of the town and left nearly 200 men and boys dead in their wake. The Lawrence Massacre, as the raid was quickly dubbed, made national headlines. It transformed Quantrill into the chief of all guerrilla chieftains.

William Clarke Quantrill’s bloody guerrilla attack on Lawrence in 1863 prompted a Union order evacuating Southern-sympathizing civilians in four Missouri counties (Jackson, Cass, Vernon and part of Bates) known for providing pro-Confederate bushwhackers with food, supplies, munitions and intelligence.

And it prompted Union Gen. Thomas Ewing to issue General Order No. 11. The order, highly controversial even among Unionists, forcibly evacuated Southern-sympathizing civilians in four Missouri counties (Jackson, Cass, Vernon and part of Bates) known for providing pro-Confederate bushwhackers with food, supplies, munitions and intelligence. Not long after Ewing’s order took effect, guerrilla activity in those areas diminished; minus logistical support from their households, Quantrill’s men (and others) could no longer operate effectively.

This being the case, a general misconception persists among Civil War buffs and armchair generals that Ewing’s Order No. 11 had finally cracked the code for dealing with Missouri’s guerrilla epidemic. In turn, it’s often proposed that Ewing’s example might yield similar results in modern guerrilla wars. But rather than cracking the code, Ewing had simply discovered that a code existed. And rather than actually snuffing out the pro-Confederate insurgencies in those aforementioned counties, Order No. 11 merely shifted the operational orbits of their insurgents to other parts of the state.

Then in spring 1865, the Confederacy collapsed. Without regular Confederate armies in the field to absorb the lion’s share of Union military attention, bushwhackers in western Missouri had little chance of keeping up (or surviving) a prolonged fight. The vast majority surrendered, while others went to Texas, Kentucky and even Mexico.

Because of this timeline, Ewing’s policy never had a long-term trial. Even so, its short-term results yielded important insights that connect the Civil War’s guerrilla conflict to more modern counterinsurgency efforts. Ewing was fundamentally correct to target the households that made the waging of guerrilla warfare possible. These logistical centers were, after all, the one part of the guerrilla equation that wasn’t mobile — the one element of the operation that couldn’t flee into the bush, living to fight another day. Where Ewing’s plan likely would have failed, however, is that it fostered no goodwill with the people who supported guerrillas, nor did it utilize overwhelming, catastrophic force to stamp out the irregulars once and for all. In other words, Ewing knew to look to the people, because without them guerrillas could not exist, but he didn’t understand what to do with that knowledge.

From the perspective of a larger power attempting to eliminate an insurgency or guerrilla movement, there are two choices:

1. Improve the circumstances of the people who support guerrillas so that doing so is no longer in their interest (and then protect them from disgruntled, diehard insurgents), or

2. Treat the enemy as a cancer that must be destroyed entirely or not at all. If the cancer is only partially removed, it will regenerate again and again. In other words, a piecemeal approach will simply create new guerrillas faster than they can be eliminated.

Ewing’s Civil War experience cannot tell us which strategy is more viable in contemporary conflicts. Both would require extensive tolls of blood, money and willpower.

But Ewing’s struggle against guerrillas on the western Missouri front does teach us one very important lesson that American military strategists in the Middle East and Africa appear determined to resist: There is no good in fighting an insurgency on its own terms. This was a lesson Ewing knew all too well — it was taught to him personally by the likes of Quantrill, “Bloody Bill” Anderson, George Todd, Clifton Holtzclaw and myriad other well-known bushwhackers.

Matthew C. Hulbert teaches history at Texas A&M University at Kingsville. His latest book, “The Ghosts of Guerrilla Memory: How Civil War Bushwhackers Became Gunslingers in the American West,” has just been released by the University of Georgia Press.