SOUTH CAROLINA: SC Attorney General Threatens Lawsuit After Robert E. Lee Marker Removed By Charleston

S.C. Attorney General Alan Wilson is threatening to sue the city of Charleston after a marker celebrating Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee was quietly removed from a downtown school last summer.

Wilson said he will take the issue to court accusing city leaders of violating the state’s Heritage Act if the marker signifying a “Robert E. Lee Highway” is not returned to its placement in front of the Charleston Charter School for Math and Science at 1002 King St.

The stone-and-metal marker was removed July 20 and placed in storage, the city said Feb. 17. The request originally came from campus officials and was later backed by the school district.

The issue had been a quiet one and little noticed until this week when a group called the American Heritage Association raised it as a potentially illegal move since the Heritage Act requires Statehouse approval for the removal of war and other history monuments on public land.

Wilson, a Republican, supports the association’s argument and said he will take the issue to court if the city does not return the marker back to the campus.

“The Lee Memorial plainly constitutes a monument or memorial to the ‘War Between the States’ or a structure dedicated in memory of a historic figure,” he wrote in a media statement. “Under the law, the City of Charleston has no right to remove this tribute to General Lee. Only the General Assembly may do so.”The city has declined to return the marker, setting the stage to allow the matter to be settled in court.

“Courts exist to resolve sincere differences of legal opinion, which is what we have in this case,” said city spokesman Jack O’Toole. “Attorney General Wilson believes the Heritage Act applies, the city’s legal department disagrees, and the courts will make the final determination. That’s exactly the way the system is supposed to work, and the city is prepared to begin that process as soon as it’s called upon to do so.”

The city legal department also defended its interpretation.

“The city of Charleston strongly respects the rule of law and recognizes the authority of the Heritage Act,” City Attorney Julia Copeland said. “We simply do not believe it applies in this case. And we look forward to reaching an agreement with the (United Daughters of the Confederacy) that satisfies the concerns of all involved.”

When asked for further explanation of the city’s legal stance, Copeland said the removal had legal precedence.

“Put simply, the city’s removal of this marker did not violate the Heritage Act based on a plain reading of the statute and a 2021 decision by the South Carolina Supreme Court. We’ll have more in our formal response to the A.G.‘s letter later this week,’ said Copeland.

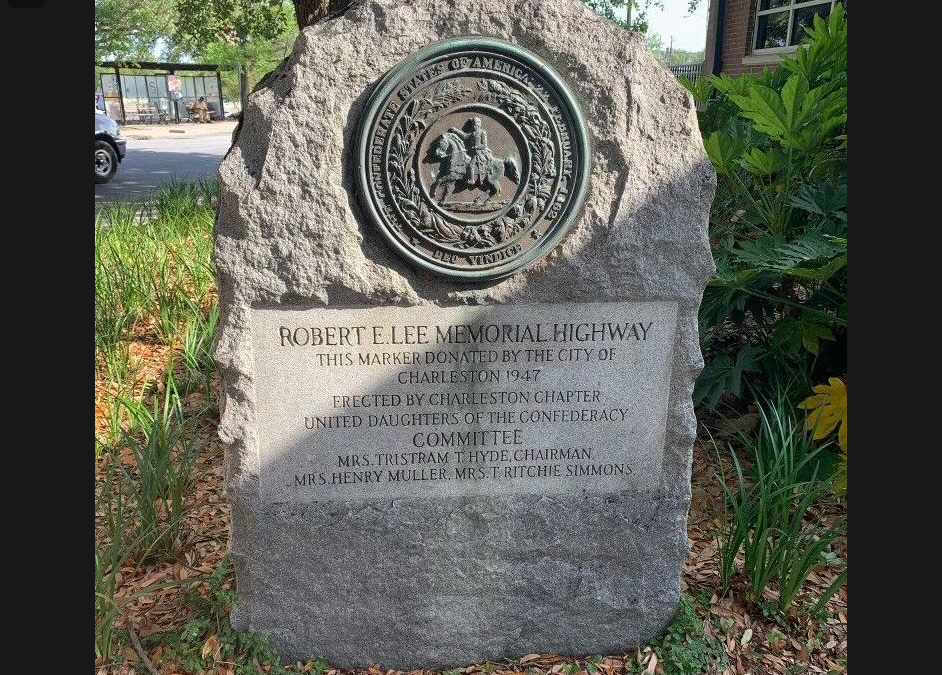

The memorial was erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy and donated to the school in 1947, the monument states. The thumb-shaped marker stands several feet tall and was one of several such markers that were placed on state roads during the middle part of the 20th century by the UDC.

The website Historic Columbia includes a description of that city’s Lee marker on Gervais Street that’s nearly identical to the one removed from the Charleston school.

It also has a description of why the marker is there.“Through public monuments and educational programs, the UDC glorified the Confederacy, explained secession as a political act rather than a defense of slavery, and vilified the federal government’s empowerment of African Americans during Reconstruction,” the website states, adding the UDC in South Carolina celebrated the Confederacy by designating a series of roads “that crossed the state from Charleston to Greenville” to Lee.

The marker itself is described as featuring “the seal of the Confederate States of America and its depiction of George Washington, which the Confederacy had used to legitimize its claim as the second coming of the American Revolution,” the website states.

The website also notes that Interstate 26 replaced the system of roads that composed the Robert E. Lee Memorial Highway when it was constructed between 1957 and 1969.

In a letter sent several months before the marker was taken away last year, former Charleston County School District Superintendent Gerrita Postlewait requested the removal of the monument and referenced its supposed historical inaccuracy.

“It is our understanding that you have confirmed with the South Carolina Department of Transportation that the King Street has not been designated as Robert E. Lee Memorial Highway,” Postlewait wrote in the Feb. 17, 2021, request.

The DOT could not be immediately reached.

But the removal authority position differs with how the American Heritage Association sees the law. The group “is now considering all legal options and remedies to have the Lee Memorial re-erected in its original state as soon as possible,” according to a news release that calls the removal both a violation of the Heritage Act and “misconduct in office.”

“Lee’s virtues and character are timeless, and they are worthy of emulation for all generations of Americans to come,” AHA board member Kyle S. Sinisi also said in the release.

The AHA has made headlines in recent months for organizing a campaign against the formation of the city’s racial conciliation commission and filing a lawsuit against the city to prevent it from lending a statue of John C. Calhoun to a Los Angeles art exhibit. The city is now in the final stages of an agreement to send the statue to the South Carolina State History Museum. The AHA also opposes that proposal.

Wilson has in the past sided with the city in one focal dispute involving the Heritage Act. He deemed the city’s removal of a statue of John C. Calhoun in 2020 in compliance with the act since the Washington Light Infantry Sumter Guards owned the property where the Calhoun statue had stood for 124 years.

He did, however, issue a legal opinion against those who sought to deem the act unconstitutional.

The Heritage Act was created as part of a compromise that led to the removal of the Confederate battle flag from the Statehouse dome in 2000. It forbids removal from public property of other flags or memorials for any war, historic figure or event without a two-thirds vote of the Legislature. In the 20 years since it was passed, legislators have only taken up a Heritage Act issue twice, most notably when they removed the battle flag from Statehouse grounds in 2015.

Lee emerged as the dominant leader of Confederate forces during the Civil War in charge of the South’s Army of Northern Virginia. He was a popular figure promoted by the UDC in the decades after the Southern defeat as the women’s group tried to gain staunch control of the narrative on the war and causes of secession.

–postandcourier.com