NORTH CAROLINA: Unique partnership aims to preserve Black history in south Charlotte

Nestled among the trees next to the bustling shops, restaurants and homes of Morrison Place in SouthPark, sits a historic landmark known only to few.

The land was once the home of an African American church and cemetery built following the Civil War thanks to the efforts of churchgoers who wanted a place of their own where they could worship with dignity.

The church moved in the 1920s and the land became pasture. Eventually, all that remained were the burial sites. There are no headstones to honor those buried there, only a few field stones and periwinkle covering the ground.

Now, thanks to a unique partnership between the developer who bought the SouthPark land and a group of the church’s descendants, the story of the church and those who worshiped there will be celebrated and the land it once stood on protected and preserved for generations. There also are plans to transform the space into one that all community members can enjoy while honoring its legacy.

“It’s going to be a beautiful project,” says Wayne Johnson, who has ancestors buried in the cemetery. “These sites are hallowed ground.”

The groups have come together to create the St. Lloyd Presbyterian Cemetery Foundation, whose mission is to revitalize and preserve the cemeteries in SouthPark and Grier Heights and bring awareness of the unique cultural heritage of the church, its members and their descendants. In February 2024, to mark the 156th anniversary of the church’s founding, the foundation kicked off a capital campaign to support the restoration of both cemeteries. SouthPark Community Partners, the economic development nonprofit that serves this part of Charlotte, is partnering with the cemetery foundation to preserve and enhance the site as a vibrant community gathering space.

Historian Dan Morrill, who is familiar with the property, describes the site and the effort to save it as “very special.” He says all of Charlotte stands to benefit as the story of the church and its congregation is more widely told.

“The history and story behind the church and the cemetery is incredible. I’ve always felt it was a compelling place,” Morrill says. “A community takes on a totally different meaning when it understands those layers of time that have occurred there.”

An ancestral connection

When Johnson looks at the site where the church once was, a wooded area nestled between Colony Road and the SouthPark Morrison high-rise apartments, he feels a connection to his ancestors who worked on the farms and in the homes along Sharon Road.

SouthPark in the 1800s, or Sharon Township as it was then known, was a rural agricultural community surrounded by farmland. Sharon Road was a dirt road that “led nowhere,” while Colony Road consisted of a narrow dirt path, according to historical accounts.

Following the Civil War, a group of African American members of the Sharon Presbyterian Church asked the church elders for “advice and aid in building a house of worship for the colored people.”

The elders agreed to let the formerly enslaved people leave the church without censure to form their own house of worship. In 1868, five trustees of The Presbytery of Catawba of the United Presbyterian Church of America signed a deed to purchase one acre of land in Sharon Township for $25. This became the home of St. Lloyd Presbyterian Church, a cemetery and a primary school. The church was named after William Lloyd Garrison, a white man from Massachusetts who was active in the abolitionist movement, Morrill says.

In 1926, the church’s land was sold to former North Carolina Gov. Cameron Morrison, who built a large farm with cattle, sheep and pigs. The church moved to Grier Heights, where members worshiped until the church closed in the 1960s. The farm, meanwhile, was eventually sold and developed into the mix of retail, offices, and established neighborhoods that make up SouthPark today.

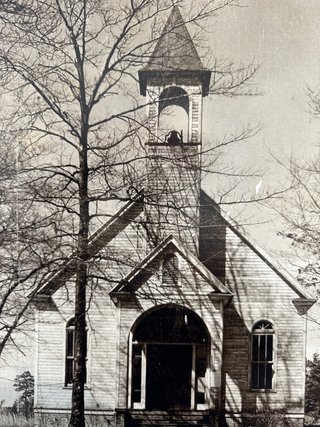

It is unclear what happened to the church building, which is thought to have been a one-story wooden structure with a bell tower in front. Historical records say it may have burned down. The gravesites, meanwhile, lay largely unnoticed, and the church’s history forgotten, until a developer bought the land.

A surprising discovery

In 2004, Grubb Properties bought three parcels of land near the busy northwest intersection of Sharon and Colony roads with plans to build high-rise apartments. The apartments were to be part of an adjacent project, Morrison Place, a mixed-use specialty center with retail, restaurants, and condominiums.

The purchase included a diamond-shaped parcel marked as the St. Lloyd Presbyterian Church Cemetery. The developer could have simply moved the graves and built on the land, located at a highly desirable and commercially valuable intersection. Instead, CEO Clay Grubb commissioned the Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission to do a study to learn more.

The study’s author determined the site was significant, citing the church’s once large presence and the well-preserved burial site with graves dating roughly from 1868 until 1926; the church’s location as one of the few remaining reminders of the rural farming community that once stretched along Sharon Road; and how the cemetery was the only surviving remnant of a church congregation that established its own house of worship in response to African Americans’ newfound freedom following the outlawing of slavery.

“It is clear that in the half-century following the Civil War St. Lloyd Presbyterian Church was central to life in Sharon Township,” according to the study prepared by Hope Murphy. “In this rural area it provided spiritual guidance, acted as a social outlet for African Americans, and provided a forum for developing black leadership. It also served, in a time characterized by racial animosity, as a place of refuge, comfort, and encouragement for African Americans.”

The site was designated a Charlotte Historic Landmark. Grubb and his family created a nonprofit to manage the cemetery site and committed a portion of the sales of the first phase of development of Morrison Place to pay for the cemetery’s maintenance and improvement.

“I wanted to be a part of preserving that history, not destroying it,” Grubb says.

Morrill, who is the former consulting director of the Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, says under different circumstances, the cemetery site could easily have been paved over.

“It would have been totally possible to remove the human remains and rebury them in another place,” he says. “Clay was wonderfully cooperative and understood the significance and importance of the site.”

Years passed, and then in 2022 Grubb received a call from Johnson, who said he had an idea he wanted to run by him.

A meeting of like minds

Johnson grew up attending St. Lloyd Presbyterian Church in Grier Heights. He and his family would often visit the church’s cemetery on Wendover Road, cleaning his great grandfather’s and great grandmother’s gravesites. Johnson remembers talking with his family about his ancestors, including those who were buried at the cemetery in SouthPark.

Johnson had known Grubb for years, having been introduced to one another by a mutual friend.

One day in 2022, after participating in a cleanup project at the St. Lloyd cemetery in Grier Heights, Johnson thought about the church’s cemetery in SouthPark and reached out to Grubb.

As Johnson describes it, it immediately became clear the two men were of like minds.

“When we started talking, his spirit was right in my spirit. We had the same idea: Combine the land and make it one piece,” Johnson says. “And he has given his heart and soul into that.”

Grubb helped Johnson and the other descendants establish the St. Lloyd Presbyterian Cemetery Foundation. The nonprofit the Grubbs had created years earlier donated the

SouthPark cemetery site plus additional land, 2.1 acres in all, to the foundation. Board members include a mix of descendants and representatives from Grubb Properties. Grubb serves as president and chairman.

“The beauty is the cemetery is preserved permanently,” Grubb says. “There is room to give the gravesites the respect they deserve, while also having some more active space. It becomes a really wonderful thing for the overall community.”

A space for reflection

Foundation board member Genora Fant was baptized at St. Lloyd Presbyterian Church’s Grier Heights location and also has been involved in beautification projects at that site. She says she never anticipated being able to make improvements to the SouthPark cemetery location and is thrilled to see what will be done.

“This has exceeded what I expected,” says Fant, whose great grandmother and great, great grandmother attended St. Lloyd Presbyterian Church in SouthPark. Fant would like to see public artwork on the site, and perhaps benches where people can sit and reflect. She would like additional research to discover more about those buried at the site. There are no headstones, but at least 78 graves have been identified and more are expected to be discovered. There is talk of a marker listing the names of those buried in the cemetery.

“A lot of information or history has been paved, over, moved, knocked down throughout history,” Fant says. “My message and hope would be: Let’s take a minute to remember. Throughout the city you see historical landmarks of what happened at that place. I would like some acknowledgement of what took place in the 1800s. That history would be very meaningful. Heartwarming, also.”

Johnson, meanwhile, is thrilled his ancestors and those who lived in the area will finally get recognition for their contributions to the city’s growth and he looks forward to seeing their story shared.

“They worked in the fields. They did all the chores, from construction to sewing, whatever it took to build a community,” he says. “Thank God my ancestors won’t be forgotten.

–bizjournals.com