TENNESSEE: The flow of time: The Tennessee River in Chattanooga has seen more than 10,000 years of human history

The 652-mile-long Tennessee River has seen some things in its time. From Knoxville through to Paducah, people have set up shop along the river’s waters. In our neck of the woods, the river has seen more than 10,000 years of human history. It’s seen the birth of Chattanooga, the city’s highs and lows and the city’s renaissance. There would be no Chattanooga without the Tennessee River, so let’s take a stroll – or swim – through time to understand our relationship to our river.

10,000 Years

Before there was Chattanooga, there was Tsatanugi, or “rock coming to a point.” The indigenous word refers to Lookout Mountain, which stands out among the city’s skyline. In the Chattanooga area, human history dates back tens of thousands of years, long before we had the Chattanooga Choo Choo or the first Coca-Cola bottling plant or the Tennessee Aquarium or the iconic Walnut Street Bridge.

From Lookout Mountain, one can see the Tennessee River curve around a peninsula of particular historic importance: Moccasin Bend. The bend has witnessed thousands of years of important events, dating back to the Paleo-Indian Period, according to the National Park Service. Through the millennia, Moccasin Bend saw nomadic Native Americans become permanent residents, and it saw the arrival of Europeans to the area.

Waterways were popular for settlement because they provided opportunities for transportation and trade, among other things, says John Dever, a National Park Partners board member and experienced river history guide from his time with the Tennessee Aquarium.

Perhaps the best-known Native American group in the Chattanooga area is the Cherokee.

In their relations with settlers, the Cherokee experienced a cultural revolution, Dever says. For example, mission schools, like the one in Brainerd, focused on “re-educating” Cherokee children, teaching them European ways.

“Naturally, when you do that to any people, they’re very conflicted about changing everything that they’ve known – their belief systems as well as their technology as well as their economic ways of life,” he says.

The discovery of gold in Northwest Georgia increased the fever for land and the expulsion of natives. In 1830, U.S. President Andrew Jackson signed into law the Indian Removal Act to force Native Americans westward, the National Park Service states. By 1838, the federal government began rounding up the Cherokee for removal.

Ross’s Landing, named for Cherokee Chief John Ross, served as the site of the first three detachments of forcibly removed Cherokee along the Trail of Tears. The first two detachments saw Cherokee crowded onto flatboats pulled by steamboats, while the third detachment saw Cherokee crossing the Tennessee River and traveling by land to Alabama, where they took boats west.

A large public art display at Ross’s Landing, known as The Passage, showcases Cherokee symbols and language, with plaques explaining the meaning of the works and providing historical context. The display reminds modern-day Chattanoogans of the people who once called this area home.

“History doesn’t belong to one people or another people. It doesn’t belong to one culture or another culture,” Dever says. “History is history. And the history of this area is our collective story.”

Photo contributed by TVA / Franklin Delano Roosevelt visits Chickamauga Dam on Labor Day weekend in 1940.

Photo contributed by TVA / Franklin Delano Roosevelt visits Chickamauga Dam on Labor Day weekend in 1940.“A Vagrant Stream”

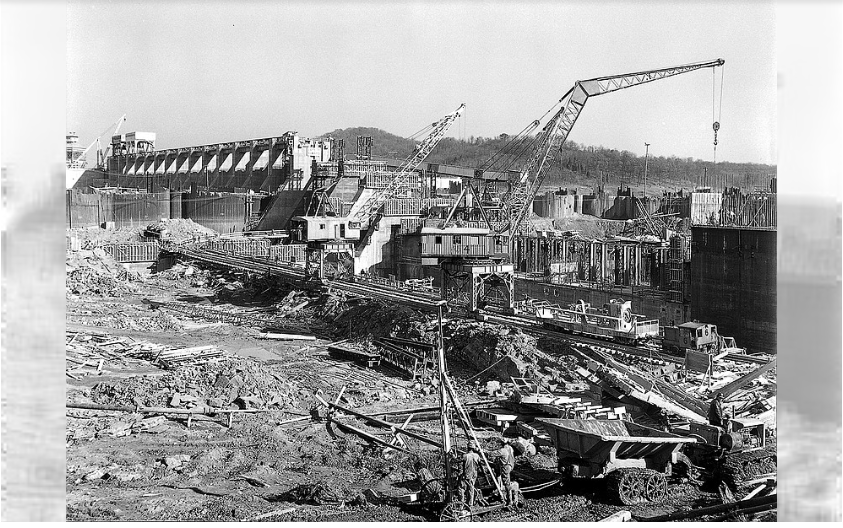

On September 2, 1940, the President of the United States, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, addressed the public at the Chickamauga Dam during a celebration of the dam’s completion.

“When I first passed this place, after my election but before my inauguration as president, there flowed here, as most of us remember, a vagrant stream sometimes shallow and useless, sometimes turbulent and in flood, always dark with the soil it had washed from the eroding hills,” Roosevelt said. “This Chickamauga Dam, the sixth in the series of mammoth structures built by the Tennessee Valley Authority for the people of the United States, is helping to give to all of us human control of the watershed of the Tennessee River in order that it may serve in full the purposes of mankind.”

Prior to development along the Tennessee River by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), there were long-standing flooding issues in the Tennessee Valley, and while some sections were navigable, people could not travel the entire length of the river due to hazards such as whirlpools and eddies, TVA historian Pat Ezzell says. These problems impeded economic progress, and other indicators such as jobs and health show that this region lagged behind before the establishment of TVA, Ezzell says.

“As bad as conditions were elsewhere in the nation when the Great Depression hit, the people here were living so poorly [that] they didn’t even know there was a depression,” she says of the Southeast.

TVA’s story begins in the era of World War I, Ezzell explains. In need of munitions and concerned what it was receiving from Chile would be intercepted by Germany, the U.S. initiated the construction of two nitrate plants and a hydroelectric dam at Muscle Shoals, Alabama. The war ended just as the plants were ready for operation, so the U.S. had $130 million worth of facilities to deal with. Titan of industry Henry Ford offered to buy the facilities for $5 million, but U.S. Senator George Norris (Nebraska), who was a proponent of using the Tennessee River for development of the region for the public good, said this was a bad deal for the American people.

As it goes, Ford eventually gave up on trying to acquire the facilities, and with the “perfect storm” of the Great Depression, Roosevelt’s election, facilities in need of use and the condition of the Tennessee Valley, the Tennessee Valley Authority was created in 1933. In the Tennessee River system, there are 49 dams, some providing power and others providing flood control and recreational opportunities, according to the TVA website.

The taming of the Tennessee River allowed the region to dramatically improve, Ezzell says. It was an experiment on a grand scale, and it worked.

Staff file photo / The Riverfront Parkway and a walkway underneath the road leading to the river between the Chief John Ross Bridge and the Tennessee Aquarium are under construction here in 2003.

Staff file photo / The Riverfront Parkway and a walkway underneath the road leading to the river between the Chief John Ross Bridge and the Tennessee Aquarium are under construction here in 2003.$120 Million Later

Walking along the riverfront in downtown Chattanooga, it’s hard to imagine it as anything other than what it is today. It’s hard to imagine the city not having that connection to the Tennessee River, but two decades ago, the riverfront looked vastly different.

Now, Riverfront Parkway is a two-lane, tree-lined road with wide sidewalks that accommodate bicycle and pedestrian traffic from the Hunter Museum of American Art all the way to the Southern Belle. Ross’s Landing and the Chattanooga Green provide ample space for recreation and celebration, with a variety of events held at these spaces throughout the year. Back in the day, however, the area was home to a multi-lane state highway that hindered Chattanoogans’ connection to the riverfront.

As former Chattanooga Mayor Bob Corker (term: 2001-05) tells it, he was out by the Tennessee Aquarium one day, looking around and recognizing that the waterfront, aside from the aquarium, was “just hot pavement with litter blowing across it.” When running for mayor, Corker’s platform had six key elements, none of which were focused on the riverfront. But it was “within our destiny to truly connect to the waterfront,” Corker says.

“The Tennessee River is what made Chattanooga, what caused Chattanooga to be an important destination and location since our founding,” Corker says. “But over time … we actually turned our back on the river as the city began to develop and change. And yet again, it was the reason for our existence in the beginning.”

Through numerous meetings with the community and various stakeholders and the raising of $120 million in public and private funding, the 21st Century Waterfront plan came about, envisioning a downtown Chattanooga where Riverfront Parkway was more pedestrian-friendly, where local attractions were enhanced and where the community had real connection to its riverfront. Corker announced the plan at his first State of the City address in 2002, and in 2005, the 21st Century Waterfront opened, bringing Chattanoogans closer to the river that made their city.

“It was just an incredible undertaking, and what I found in meeting with people about raising the money for it was that people became incredibly excited about something that was transformative for our community and that was going to happen in 35 months, meaning that it was going to happen in their lifetime,” Corker says.

The 21st Century Waterfront gave Chattanooga a boost of confidence – a “shot in the arm” – that something so large, so transformational, could happen with the whole community involved, Corker says. Another boost is on the horizon as planners seek to again redevelop the riverfront, making it “a place for everyone, 365 days a year,” and “building upon the legacy and design of the 21st Century Waterfront.”

Learn more about the new vision at riverfrontparkscha.com. For more information on TVA, go to tva.com.

Staff file photo / A track hoe digs into the bank of the Tennessee River in 2003 as construction continues on a ramp to the river as part of a Trail of Tears memorial next to the new Tennessee Aquarium building, also under construction nearby.

Staff file photo / A track hoe digs into the bank of the Tennessee River in 2003 as construction continues on a ramp to the river as part of a Trail of Tears memorial next to the new Tennessee Aquarium building, also under construction nearby.