GEORGIA: Georgia Teen’s Civil War Diary to Be Published

MACON, Ga. — LeRoy Wiley Gresham’s short, painful life in Macon ended about the same time as the Civil War, but he left behind a legacy treasured by historians.

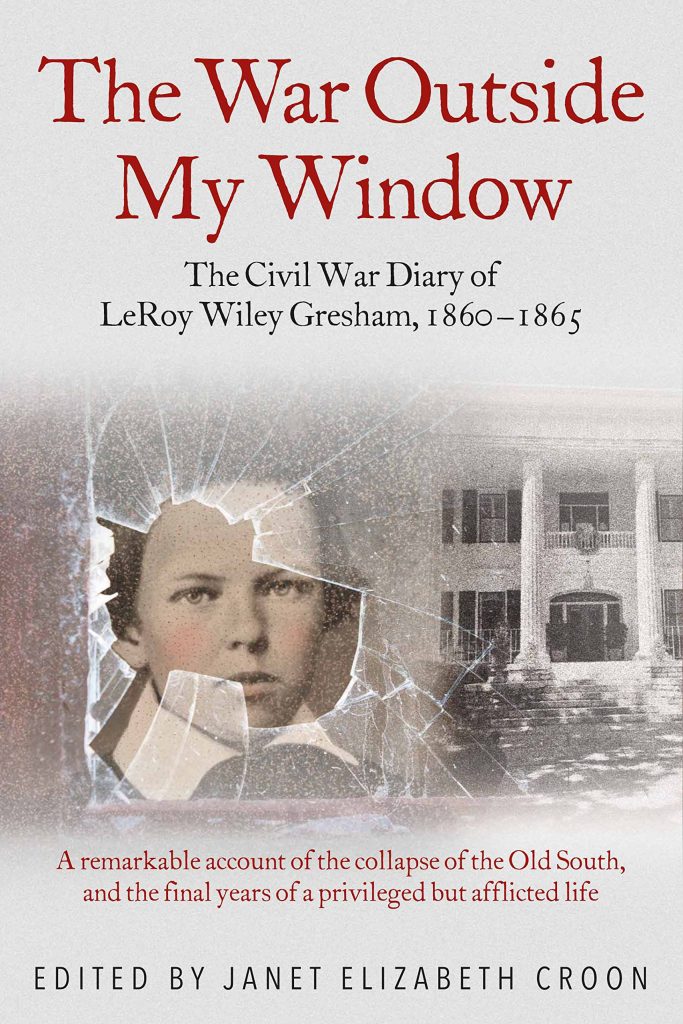

Starting in 1860 at the age of 12, a few months before Georgia seceded from the Union, he started keeping a diary and did it almost daily until his death on June 18, 1865, two months after Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, Virginia. Now, for the first time, the diary has been put in book form, called “The War Outside My Window.” It will be available on Amazon beginning Friday, published by Savas Beatie, a company that specializes in historical books.

Janet Croon, a retired history teacher who lives in Virginia, transcribed the diary using the online copies of the original seven volumes in the Library of Congress. She was not able to get her hands on the actual diary.

But she did much more than transcribe it. She is also a genealogist and extensively researched records to create a listing of the many people LeRoy mentions in the book, with details on exactly who they were. The book also includes extensive footnotes explaining, and often correcting, LeRoy’s many statements about events of the war and things happening in Macon at the time.

“It has been an honor to pull this out because it so unique,” Croon said. “It was just a passageway into another time period through someone else’s eyes. I just think it is so valuable for a lot of different reasons.”

LeRoy lived on College Street and his home is still there, known today as the 1842 Inn. It is a favored spot for celebrities visiting Macon. LeRoy is buried, along with his parents John and Mary Gresham, in Rose Hill Cemetery. John Gresham served as mayor of Macon and owned two plantations in Houston County, both of which were just west of the Ocmulgee River where Ga. 96 crosses today. Croon determined the location by looking at land records in Houston.

Before the war, LeRoy was seriously injured when a chimney fell on his leg. He was unable to walk, and could only leave the house by a special wagon pulled by family members or slaves.

He spent most of his time indoors devouring newspapers, books and whatever else he could get his hands on. He is quick to offer critiques on his latest reading material, as well as opinions about the war, politicians and generals. His reading material included Charles Dickens and Shakespeare.

Central topics of the diary are the war, his health, the weather and the events of the day in his household.

He chronicles the beginning of the war with an entry on April 13, 1861, that reads “War! War! War! The firing on Sumter is still going on. … The abolition party in Washington terribly frightened.”

He talks frequently about the pain he is in, and often found it difficult to sleep. He often wrote “Saw off my leg.” His parents tried a variety of “medical” products to no avail. He was often given morphine and he also mentions being given whiskey.

But as it turns out, his death had nothing to do with his injury.

Croon had a physician read the diary and following LeRoy’s description of his symptoms, he came to the conclusion that he died of tuberculosis.

Local historian Phil Comer was excited to hear the news that LeRoy’s diary is coming out in book form. Comer had only been able to read excerpts of it previously, and he immediately ordered an advanced copy as he found out the book was available.

“It’s a shame he didn’t live to adulthood because he was a brilliant young man and an excellent writer,” Comer said as he stood in front of the 1842 Inn recently. “LeRoy is a young voice of the Civil War.”

Croon will soon be making her first visit to Macon and is looking forward to seeing Gresham’s home, grave site and the area he describes. On June 9 she and publisher Ted Savas will hold a launch event for the book at the 1842 Inn at 353 College St. from 1-2 p.m. They will be signing copies of the book.

Among notable events LeRoy chronicles in the book are the raising of the Confederate national flag in Macon following secession and a fireworks celebration of secession. He also heard the cannon shot that gave the Cannonball House its name. He kept his diary until two weeks before he died in 1865, shortly after the war ended, along with his world as he knew it. He chronicled the chaos that enveloped Macon as the war drew to an end.

The last few entries of his diary are LeRoy’s words transcribed by his mother. The last entry, on June 9, 1865, reads simply “I am perhaps.” Croon speculates in a footnote that LeRoy said “I am perhaps dying,” or something along those lines, and his mother could not finish it.

###

—macontelegraph.com