GEORGETOWN — Before Paige Sawyer begins one of his walking tours, the self-described “seventh-generation South Carolina redneck” tells his customers to meet him at the fountain.

By that he means the big, brown polished granite bowl that sits atop a base and pedestal, overflowing with water and just a stone’s throw from Georgetown’s tall Town Clock.

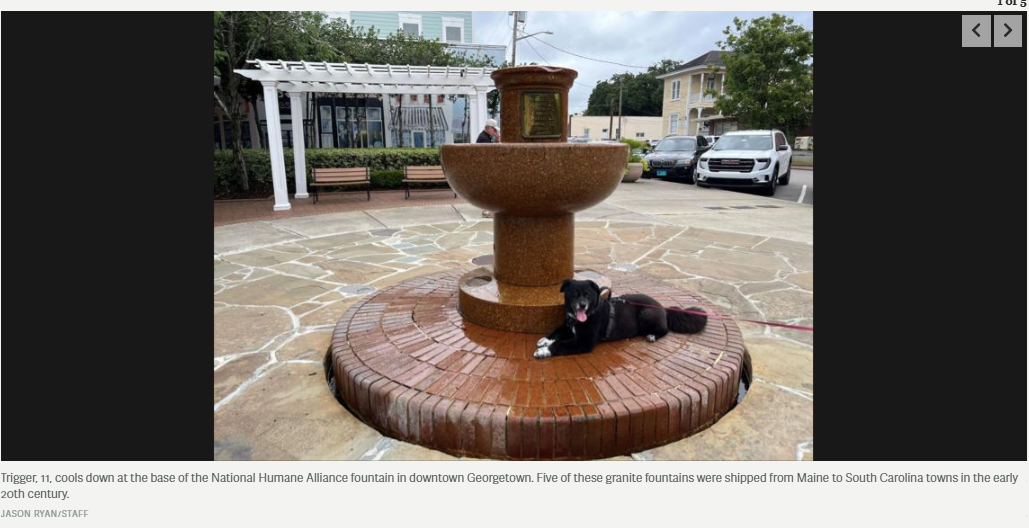

There’s often a dog around the fountain, as was the case on a recent Saturday morning. A black-coated pup with white socks named Trigger slurped from low bowls and plopped down on water-soaked bricks just as Sawyer began giving his historical spiel to two clients.

Little did Trigger know that Georgetown isn’t the only place in South Carolina he can enjoy such a watering spot. During the early 20th century, an animal advocacy organization donated more than a hundred granite fountains to cities across the United States, all made from stone quarried and carved in Maine. So long as a municipality agreed to place the fountain in a prominent intersection, where horses and other animals could drink, the National Humane Alliance would send a five-ton fountain, free of charge, freight included.

Five of these squat, stately fountains arrived in South Carolina from 1907 to 1912. They were placed in busy intersections in Abbeville, Camden, Columbia, Georgetown and Laurens.

More than a century later, the fountains are all intact and standing. At least four, however, have been moved from their original sites, which became problematic when automobiles began to replace horses. Most are still spitting water — points of pride for these communities given that other municipalities have let their fountains run dry, turned them into flower planters or lost the giant gifts entirely.

The free fountains came courtesy of Herman Lee Ensign, an advertising mogul who died in New York City in 1899. He left the bulk of his estate to the National Humane Alliance, an organization he created to spread “ideas of humanity both to the lower animals and to each other.”

Ensign reasoned that teaching young people to love animals might also allow them to love their fellow man. The executor of his estate put this philosophy into practice by paying for the manufacture of the granite fountains.

The offerings came in two similar styles and sizes, each comprised of five parts that stacked atop each other, beginning with a wide pedestal on the ground which was topped by a base, which was topped by a wide bowl, which was topped by a block and then capped with a roof. Cast iron lion heads adorned three sides of the block, spouting water from their mouths into the wide bowl where horses could drink.

Small bowls were carved into the base below the bowl, providing water for dogs, cats and other small creatures. A metal plaque bearing the National Humane Alliance’s name adorned another side of the fountain. Sometimes a metal chafing ring encircled the bowl to protect the granite from the metal pieces of a horse’s harness.

Today, James Dickey describes the fountains, measuring up to 6 feet wide, as “gas stations for horses.” He is a descendant of one of the owners of Bodwell Granite Co. in Vinalhaven, Maine, which carved the fountains in the early 20th century. At that time, Maine granite also served as a crucial resource for making the roads, bridges and buildings of an expanding and industrializing America. Beyond being used for construction, Vinalhaven granite was cut and carved into cathedral columns, war monuments, lighthouse foundations and impressive eagle statues that adorned public buildings.

Though Bodwell Granite closed decades ago, Dickey, a retired ferryman, still occasionally makes replacement parts for fountains, such as a 600-pound, 20-inch granite cube he recently hollowed out for a fountain in Vicksburg, Miss. He has hopes of restoring local quarries as museums in Maine and teaching stonecutting to future generations. He aims to keep alive the legacy of an industry that hides in plain sight on Vinalhaven, an island community of coastal Maine where discarded chunks of granite, some of which weigh more than a ton, line the roads and jut out of patches of grass.

The rubble scattered across the island includes a handful of rejected, half-finished fountain bowls. Men carved these giants hunks for months before the emergence of cracks doomed the pieces and caused them to be cast aside, where they lie forgotten by all but Dickey and perhaps a few other islanders.

The National Humane Alliance is more or less forgotten these days, too, with its surviving fountains serving as the organization’s sole legacy. The Vinalhaven Historical Society has collected information on the fountains and created a map of their locations across the country and as far away as Havana, Cuba, and Mexico City, Mexico.

A website associated with the town of Derby, Conn., has also created an interactive map and gathered information about the old fountains, with the website’s creator, John J. Walsh, even once helping broker a sale of an unused fountain. The website helps to preserve the mission of the National Humane Alliance, which reads, in part: “(The alliance) desires to educate people, particularly the rising generation, to be kind and gentle among themselves and to treat all dumb animals humanely. … The idea is that you make better citizens as you eliminate cruelty and brutality from the mind and instill gentleness and kindness …”

It’s a sweet thought, for water to wash away wickedness. Here are the five places in the Palmetto State where the National Humane Alliance placed granite fountains in an attempt to quench thirst and save souls:

Abbeville

Residents apparently picked a good spot when they installed a granite fountain at the southern end of the town’s square in 1912. According to a nearby plaque, the fountain is one of the few to remain standing in its original location.

The small fountain of brown or bronze-like granite sits in a brick-walled basin in Abbeville’s stately main square, surrounded by park benches and tall trees.

Anna LaGrone works nearby as the executive director the Abbeville Chamber of Commerce. She described the fountain as a “beautiful fixture on the square” that is regularly used by residents who dye the water to celebrate events and causes, such as turning the fountain’s water pink in October during Breast Cancer Awareness Month.

“It’s currently blue and I’m trying to figure out why,” said LaGrone in July.

Ensign, the late, animal-loving millionaire who paid for the fountains a century ago, would be pleased to know that Abbeville’s four-legged fur babies make use of his gift, as LaGrone said her dog Hank once splashed around during a visit to the square.

“Before I could stop him, he jumped into the fountain and was as happy as a clam,” LaGrone said. “He seemed to think it was the perfect place to cool off.”

Camden

When Camden received its fountain in 1910, the city promptly dedicated the monument in the name of Confederate war hero Sgt. Richard Rowland Kirkland. Schoolchildren collected money to pay for a plaque on the fountain that recognized the native son known as the “Angel of Marye’s Heights.”

In December 1862, Kirkland fought in the Battle of Fredericksburg, Va., as part of the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers. During a lull in the fighting, Kirkland is said to have been so bothered by the cries of agony from wounded soldiers who lay beyond a stone wall that he obtained permission from his commanding officer to provide relief to the enemy.

“I can’t stand this. … All night and all day I have heard these poor people crying for water, and I can stand it no longer,” said Kirkland, according to a letter by former Confederate Major Gen. J.B. Kershaw that was published in Charleston’s News and Courier in 1880.

“Kirkland, don’t you know you would get a bullet through your head the moment you jumped over the wall,” Kershaw said he replied to the young soldier.

“Yes, sir,” Kirkland supposedly replied. “I know that; but if you let me, I am willing to try it.”

The general assented and Kirkland soon hopped the stone wall and provided water and medical care to injured Union soldiers, with both sides supposedly holding their fire until this dangerous errand of mercy was finished.

Kirkland’s luck ran out 10 months later. He was killed in action during the Battle of Chickamauga, Ga., on Sept. 20, 1863. Though he only lived 20 years, Kirkland’s legacy has burned bright since Kershaw published his account — though historians have been hesitant to accept the general’s specific recollection entirely. Other wartime accounts also mention an act of heroism as described by Kershaw, but some describe a soldier from Georgia performing the deed or state that multiple Confederate soldiers helped the injured Union troops. On the other hand, other accounts of the battle do not mention any significant pause in the fighting in which a Confederate soldier could have tended to the fallen.

In any case, Kirkland’s name is emblazoned on Camden’s fountain, which was unveiled at the intersection of Dekalb and Broad streets in 1911 on May 10, the date now recognized in South Carolina as Confederate Memorial Day.

That day a procession entered Kershaw Square and dedicated a statue known today as the Pantheon, which honors the six Confederate generals who hailed from Kershaw County, including J.B. Kershaw. Then a 700-person-strong group of officials, police, national guardsmen, veterans and school children marched to the granite Kirkland fountain, joining a waiting crowd of 1,500 others to celebrate its debut.

The fountain was immediately well received, said a May 18, 1911, article in The Camden Chronicle.

“Since the erection of the Richard Kirkland hundreds of men and beasts have slaked their thirst there,” said the report. “On Saturday afternoon last it was interesting to watch the crowds that continually thronged around it. The fountain is a public benediction.”

Decades later, in the late 1940s, the fountain stood at the southern end of Broad Street, according to research by Sarah Murray, the archives manager at the Camden Archives and Museum. When residents complained the fountain had become a road hazard, the granite was moved again in 1950, this time to the city’s Hampton Park.

Eight years later, the fountain stopped running and its fixtures were missing. The fountain was restored in 1985, but by 1999 more work was needed, including the installation of new interior pipes and the recasting of the lion head spigots.

Despite these efforts, the fountain has once again gone dry. As archivist Murray wrote in a 2024 article about the fountain, “Maintenance issues are ongoing, but after 112 years, the handsome Kirkland fountain still stands in Camden as a permanent reminder of a young soldier’s heroic actions so long ago.”

Columbia

While Abbeville’s fountain is said to have never moved, the one gifted to Columbia has been all over South Carolina’s capital city. In July 1908, a large version of the fountain was placed at the intersection of Assembly and Lady streets, a block from Columbia’s city market building. When the market building was demolished five years later, Columbia’s Curb Market took its place, with farmers lining up their trucks for blocks along Assembly Street to sell their goods under sheds and open sky. Between the farmers, their animals and the crowds of customers, the National Humane Alliance fountain provided sustenance to many.

As Columbia historian and librarian Margaret Dunlap wrote in a 2022 blog post for the Richland County Public Library: “The Curb Market was a point of pride for Columbians. Market days were held several times a week and everyone went and mingled there. It was a bustling scene. The Curb Market eventually expanded to encompass 10 blocks of the city. It was described in a 1945 guide to the city as one of the “pleasantest places in Columbia.”

Yet there was an unpleasant scene at the Curb Market on Nov. 14, 1946, when an explosion of ethylene gas used to ripen bananas killed five people. Five years later, the market moved to Bluff Road and became the State Farmers Market. Meanwhile, the National Humane Alliance Fountain was relocated to the median of Elmwood Avenue at the intersection with Bull Street.

Here it stayed for nine years, until 1960, when the completion of Interstate 126, which merged with Elmwood Avenue, forced the fountain to again be moved. This time local leaders had the fountain pieces reassembled in Earlewood Park, where it stood for 20 years, according to the Columbia History Buff blog, written by Paul Armstrong, a local historian and volunteer with Historic Columbia Foundation.

In 1980, the fountain was given to the Township Auditorium in honor of the 50th anniversary of the building’s opening. The fountain stood outside the Taylor Street auditorium for 29 years until it was placed in storage during expansion work.

It remained hidden away for three years until residents of the Earlewood neighborhood lobbied for the fountain to be returned to Earlewood Park. It stands now in the middle of a garden in the park, close to a community building.

Georgetown

When Georgetown received its fountain in 1911, a lamp pole projected out the top, capped by a glass globe.

City leaders placed the fountain in the middle of Broad Street, close to the intersection of Front Street. Later, the fountain was moved to a garden behind the Rice Museum and Town Clock. Finally, in 1993, it was moved to the corner of Front and Screven streets, where it stands today.

While Sawyer does regularly discuss the fountain’s history on his historical walking tour, he says his decision to gather with his clients around the granite monument is mostly for practical reasons — public restrooms and plenty of parking are less than a block away. But even without an introduction from Sawyer, plenty of people find their way to the fountain, especially if they are walking a dog.

When Trigger, 11, visited on a hot Saturday morning, he lingered at the fountain and enjoyed taking a sip from each bowl carved into its base.

“Oh yeah, we had to stop here,” said Trigger’s owner, Erica Ransom. “He goes from side to side drinking water.”

People are just as interested in the fountain, said Sharon Corey, manager of the Georgetown County Museum, who said visitors often stop into the museum to ask about the watering spot.

“Visitors certainly notice the beautiful drinking fountain and children are always attracted to it. Possibly it is the soothing sound of water …,” Corey said. “I am very proud of the drinking fountain and that it reminds us of the humanity of our treasured animals. I cannot imagine Georgetown without it.”

Laurens

At the turn of the 20th century, the city was judged too small to deserve a granite fountain. But lucky for the Upstate town, resident W.G. Lancaster wouldn’t take no for an answer.

After learning that Columbia received a granite fountain, Lancaster lobbied for Laurens to receive one of its own. Yet the National Humane Alliance’s director, Lewis Seaver, deemed Laurens, with a population of less than 5,000 people, undeserving. This decision only spurred Lancaster to double down on his efforts to secure a fountain, as he emphasized to Seaver that Laurens was the seat of an up-and-coming county and in need “for such a place where the horses and mules and people who come in the city to do their trading might be watered,” according to a 1911 article from an unidentified newspaper.

Because he was so “earnestly and persistently solicited” by Lancaster and others, the New York-based Seaver made a visit to Laurens during a tour of the South and changed his mind. On May 8, 1911, he sent a letter to the mayor and city council to deliver good news, telling them, “The writer recently visited Laurens and inspected the proposed sites for the location of a fountain and have now decided we will furnish your city with one of our second size fountains, free of charge, freight prepaid…”

As a condition, Seaver instructed that the fountain be placed in the center of the street on the north side of Lauren’s main square. The 1911 newspaper article described its location as somewhere between the curbing near the city’s Confederate monument and the corner nearest a store owned by M.H. Fowler.

The fountain apparently didn’t stay there for too long. When Nathan Senn became mayor in 2019, he found the fountain sitting within crates in a public works yard. Apparently, it had sat there, unused and in pieces, for decades.

“It was sort of out of sight, out of mind,” said Senn, who soon had a bright idea.

In February 2020, he attended the Riley Mayors’ Design Fellowship in Charleston, a program in which he and other municipal leaders learned urban planning and leadership lessons directly from Joseph P. Riley Jr., who served as Charleston’s mayor from 1976 to 2016 and earned wide acclaim for his management of the city.

One thing Riley said during the program stuck with Senn: “Corners are very important.” With that tip in mind, Senn and his colleagues in Laurens created a new park at the intersection of U.S. Highways 221 and 76 that commemorated Black-owned businesses that once stood nearby on Back Street, a block away from the main square.

The city installed gas streetlamps in the small park along with wrought iron fences covered with Carolina jessamine, the vine that serves as South Carolina’s official state flower. As a final touch, workers uncrated the old fountain and installed the long-forgotten granite as the centerpiece of Back Street Park.

“It’s the icing on the cake. It’s what makes that park particularly special,” Senn said.

Senn, who formerly lived in Charleston and graduated from the Charleston School of Law, said Back Street Park and the fountain have proved a popular gathering spot.

“My niece had all her prom pictures taken there. I’ve actually married people in front of the fountain,” Senn said.

Though Back Street Park promotes a spirit of inclusion, there is one population ironically missing out on the water that once again flows from the fountain in Laurens.

“We get very few horses downtown these days,” the mayor said.

–postandcourier.com