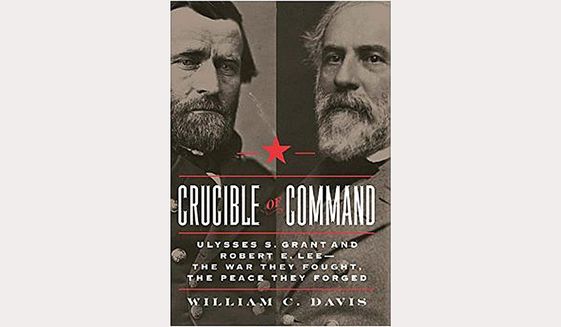

For serious historians of the Civil War, William C. Davis is the ultimate go-to source for reliable information on a conflict that spawned a staggering amount of mythology. He is the author of more than 50 books on the war and the South, and until recently was director of the Virginia Center for Civil War History at Virginia Tech.

At hand is a thick — and very readable — volume that culminates a life of serious research into all aspects of the war, including personalities, strategies and politics. Mr. Davis, fortunately for all of us, is a stickler for original and contemporaneous sources, rather than long-after-the-fact memoirs. And, indeed, the chapter notes (112 pages of them) should be read along with the text.

An example: The popular depiction in “history” of Gen. Ulysses Grant as a drunk? After studious research, Mr. Davis concludes, “This is all based on a considerable array of mythology, and virtually no contemporary evidence.” Previous biographers relied on 60-year-old “recollections.” One so-called source was an officer who was “dismissed from the service in 1863 for disloyalty,” and vainly pleaded with Grant for reinstatement. Mr. Davis also demolishes a sensational story in the Union press that Gen. Robert E. Lee personally horsewhipped a runaway slave woman.

Much of the book consists of an examination of the generals’ disparate backgrounds and personalities. Lee was the scion of Virginia First Family aristocracy, son of Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, an American Revolutionary War hero. But debt forced the father to flee to the West Indies when Robert was only six; they never saw one another again. Thereafter, a cash-strapped family lived on meager behests to Lee’s mother. Nonetheless, Lee grew to maturity under the tutelage of a loving mother. Grant’s father, by contrast, was prosperous but cold, denying his son psychic and financial support when he struggled after resigning from the pre-war army.

Mr. Davis credits Grant for realizing, early on, when he first joined an Illinois regiment, a strategy for victory. In letters to wife Julia, he opined that control of rivers and coastal waters would be more decisive than grand battles. Cutting off cotton ports such as Charleston, Savannah, Mobile and New Orleans would starve the Confederacy from foreign sales (primarily of cotton) so “it could not finance insurrection.” Thus was born what came to be known as the “Anaconda strategy,” which Grant successfully employed in the Western theater, seizing the Mississippi and other rivers and Union road to victory laid in control of rivers and other waterways in the west and bifurcating the South.

Mr. Davis makes a strong referential case that the bloody campaigns in the east were a meaningless slog, with the Union never mustering the strength to seize Richmond, the Confederate capital, nor the South making a serious effort to capture Washington. Grant viewed grabbing land as of no consequence; victory required the destruction of Lee’s army. Grant’s capture of Atlanta, and General William Sherman’s destructive march through Georgia and South Carolina, finally ended the fighting.

Lee had the strength of character to resist such loud politicians as Virginia’s Edwin Ruffin who chided him for not being a more aggressive commander — “too much of a red-tapist to be an effective commander in the field.” And indeed, Lee’s preference for fighting from defensive trenches, rather than directly in the field, caused some soldiers to deride him as “The King of Spades.” Lee, however, was astute enough to recognize the Union’s numerical superiority, and he sought to preserve his army.

Lee comes across as a deeply religious man who attributed each of his victories to “the blessing of the Almighty … He alone can give us peace and freedom and I humbly submit to His holy will,” he wrote his wife. “Thank God for victories!”

Lee did not share the strong segregationist views of the Southern president, Jefferson Davis, considering him an “extremist” politically. He strongly resisted pleas that he assume control of the Confederacy as a military dictator.

Grant spent an inordinate amount of time fending off political interference with his command, with rival generals contesting his authority. Battlefield successes enabled him to shove aside such interference. Grant also knew a bit about what is now known in the American military as “operational security.” He zealously guarded plans for pending operations so as to avoid leaks, and he took a very dim view of journalists who haunted his camps in hopes of getting advance information on planned campaigns (and printing the information in newspapers readily available to the South). Reporters howled about censorship; Grant ignored them.

At war’s end, Lee found himself destitute. Union soldiers had gleefully looted Arlington-Custis House, across the Potomac from Washington, part of his mother’s inheritance, hauling away relics from George Washington. “He had no home, no property but his clothing. Food was scarce and he had no money when it could be bought.” Friends brought farm produce to the house, and the Lees “even accepted some of the rations being dole out by Federal occupying troops .”

Worse, ignoring the terms of the Appomattox surrender, a federal judge handed down an indictment of Lee for treason. An infuriated Grant objected. He met with President Andrew Johnson and threatened to resign unless the indictment was quashed. Johnson gave in. Lee spent his remaining years as president of Washington College in Lexington, Virginia (renamed Washington and Lee after his death). Grant served two terms as president, an experience beyond the scope of Mr. Davis‘ book.

The most avid of Civil War buffs will relish the revealing details in a book rich in authenticity and readability.

• Washington writer Joseph Goulden attended high school on the site of a Confederate hospital in his hometown of Marshall, Texas.