Major General Benjamin Butler was a political general with no prewar military experience and a reputation for concocting and supporting unconventional ideas. Lieutenant Colonel Theodore Lyman, aide-de-camp to Maj. Gen. George Meade, ventured to Butler’s Richmond front during the Richmond-Petersurg Campaign and recorded some unique plans. “A fire engine to squirt down their earthworks; a petard to blow up their abbatis; an iron net, thrown by mortars, to net them; and finally an auger, 5 feet in diameter, to bore under ground to Richmond.”[1]

Lyman was a natural scientist who graduated from Harvard with honors, and while not possessing an engineering background, could tell these schemes were foolhardy. (If I had to pick one, using a small explosive to blast openings in obstructions could be useful for attacking earthworks in column under fire.) At a cursory glance, these plans did not seem to develop further and may have been fabricated by Lyman. One novel idea received Butler’s full support, to the extent of detaching his chief engineer far from the front to work on it. A helicopter-like flying machine designed by Edward Serrell never made it off the ground, but generated significant intrigue in its time.

An outstanding engineer before the war, Serrell worked on multiple railroad, bridge, and surveying projects. When war broke out, he formed the 1st NY Volunteer Engineer Regiment. In November 1861, he ranked as chief engineer of the X Corps and met with its commander, Maj. Gen. Ormsby Mitchell.[2] Serrell demonstrated a tin wind-up toy with two blades that could be wound up with a string, and upon release, soar into the air. Serrell explained that assuming the problems of weight and power could be addressed, adding a horizontal rotor on a shaft would provide propulsion and allow steering. This would be especially beneficial as the X Corps had a tethered balloon for observation, yet its direction was at the mercy of the winds. Mitchell encouraged further experimentation, but perished from yellow fever soon after.[3]

Serrell remained undeterred. He and two other engineers discussed making a device in this manner that would not only take off and land where the operators wanted, but could also carry bombs to drop on enemy positions. He got another break when demonstrating the tin toy to Butler during the Petersburg campaign, who responded enthusiastically and ordered Serrell to deliver an official report on the machine’s feasibility.

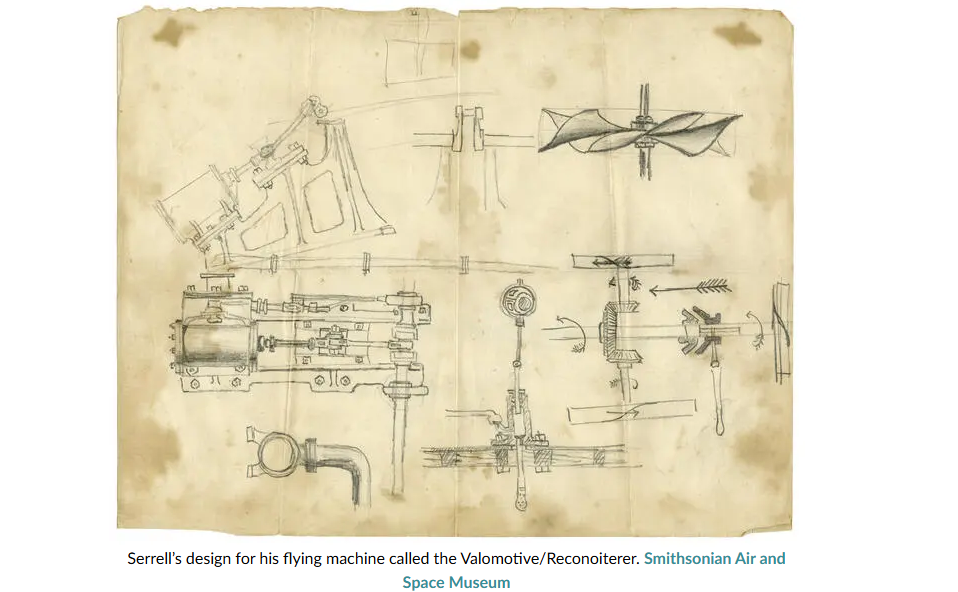

He quickly drew a design for a fifty-two-foot machine with a steam boiler, plane wings to glide, and four rotors. Two vertical rotors would generate lift, while two horizontal ones would propel the craft forward. Upon reaching altitude, it would glide as long as possible before again powering the vertical rotors to ascend. Butler immediately gave the green light, but there was no room in the Army budget for the project. In the field, advanced machining necessary to manufacture gears or bore through metal was not available. Private investments seemed to be the solution. Wealthy oil barons from New York City gave Serrell a blank check to create this craft he called the Valomotive or Reconoiterer, and he moved to NYC to develop the project.[4]

Work started with a scaled-up version of the toy with a thirty-two foot screw that could elevate 500 pounds, more than its own weight, for forty seconds at a time.[5] Serrell commissioned a lightweight, but powerful engine for the craft. Although his assumptions about lift were ahead of their time, the steam engine was the limiting factor. His team built the frame of the machine in Hoboken, but the special engine was not completed before the end of the war, and would have still been woefully inadequate to achieve flight.[6]

The military impetus for the craft ceased, but Serrell continued working the next year and collaborated with other contemporary aeronauts such as Mortimer Nelson, who patented a helicopter-like vehicle called the Aerial Car in 1861. Even P.T. Barnum wrote to Serrell, offering to exhibit the invention.

However, by the end of 1866, he abandoned the project, reverting to his prewar career as an engineering consultant.[7] Writing in 1904, he theorized that using pressurized liquid CO2 would have sufficient force to not only lift the craft, but give it an operational radius of 800 miles. These carbon dioxide engines could triple or quadruple the output of the finest steam engines while being far lighter.[8] In 2013, a Belgian company designed a helicopter with an air compressor pumping some air to the engine and mixing the rest with exhaust fumes, using heated air to drive two turbines for power. Designed as a light, personal aircraft, it never seemed to progress past the experimental phase.[9]

Closing his 1904 article, Serrell writes, “Nothing is known by the writer of the details of the machinery recently tried by the brothers Wright in North Carolina, except that obtained from imperfect newspaper accounts, but from what has been published it would seem that their machine is very much like, if not identical, with the army machine here described; but whether this is so or not, they are to be most heartily congratulated upon the measure of success that has crowned their efforts.”[10] Of course, the Wright brother’s plane was not at all similar to Serrell’s plans. He passed away not long after in 1906, long enough to see his dream of powered flight become a reality.[11]

[1] David Lowe, ed. Meade’s Army: The Private Notebooks of Lt. Col. Theodore Lyman (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2007), 300.

[2]“Edward Wellman Serrell Aeronautical Papers,” Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-archive/edward-wellman-serrell-aeronautical-papers/sova-nasm-2011-0040.

[3] Edward Wellman Serrell, “A Flying Machine in the Army,” Science 19, no. 495 (1904): 952. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1630179.

[4] Serrell, 954.

[5] USAF Historical Division, The United States Army Air Arm, April 1861 to April 1917 (May 1958), 10-11. https://www.dafhistory.af.mil/Portals/16/documents/Studies/51-100/AFD-090602-017.pdf.

[6] Serrell, 955.

[7] Edward Wellman Serrell Aeronautical Papers,” Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-archive/edward-wellman-serrell-aeronautical-papers/sova-nasm-2011-0040.

[8] Serrell, 955.

[9] “Sagita Sherpa On View,” Global Aviator 5, no. 9 (Sep 2013), 48. https://interactivepdf.uniflip.com/2/70683/312029/pub/html/48.html.

[10] Serrell, 955.

[11] “Died: Serrell,” The New York Times (New York, NY), April 26, 1906. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-new-york-times-died-serrell/102640050/.

–emergingcivilwar.com