In 1763-67 Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon surveyed and marked most of the boundaries between Maryland, Pennsylvania and the Three Lower Counties that became Delaware. The survey, commissioned by the Penn and Calvert families to settle their long-running boundary dispute, provides an interesting reference point in the region’s history. This paper summarizes the historical background of the boundary dispute, the execution of Mason and Dixon’s survey, and the symbolic role of the Mason-Dixon Line in American civil rights history.

Historical background

English claims to North America originated with John Cabot’s letters patent from King Henry VII (1496) to explore and claim territories for England. (“John Cabot” was actually a Venetian named Giovanni Caboto.) Cabot almost certainly sailed past Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland. He stepped ashore only once in North America, in the summer of 1497 at an unknown location, to claim the region for England. It is highly unlikely that Cabot came anywhere near the mid-Atlantic coast, however.

The first Europeans to explore the Chesapeake Bay in the 1500’s were Spanish explorers and Jesuit missionaries. But based on Cabot’s prior claim, Queen Elizabeth I granted Sir Walter Ralegh a land patent in 1584 to establish the first English colony in America. The first English colonists settled on Roanoke Island inside the Outer Banks of North Carolina in 1585 (see colonist John White’s map). Most of the colonists returned to England the following year; the remaining settlers had disappeared when White’s re-supply ship finally returned to the island in 1590.

The Virginia Company of London, a joint stock venture, established the first permanent English colony at “James Fort,” aka Jamestown, in 1607. The fort was erected on a peninsula on the James River. The colony was supposed to extract gold from the Indians, or mine for it, and it only survived by switching its economic focus to tobacco (introduced to England by John Rolfe), furs, etc.

John Smith published his famous Map of Virginia (1612) based on his 1608 exploration of the Chesapeake. Smith’s map includes the “Smyths fales” on the Susquehanna River (now the Conowingo dam), “Gunters Harbour” (North East, MD), and “Pergryns mount” (Iron Hill near Newark, DE). Notice that the latitude markings at the top of the map are surprisingly accurate.

The Maryland colony

When George Calvert, England’s Secretary of State under King James I, publicly declared his Catholicism in 1625, English law required that he resign. James awarded him an Irish baronetcy, making him the first Lord Baltimore. Although Calvert was an investor in the Virginia Company, he was barred from Virginia because of his religion. He then started his own “Avalon” colony in Newfoundland, but the climate proved inhospitable. So Calvert persuaded James’s successor, Charles I, to grant his family the land north of the Virginia colony that became Maryland.

The 1632 grant gave the Calverts everything north of the Potomac to the 40th parallel, and from the Atlantic west to the source of the Potomac. George Calvert died later in 1632, and his sons started the Maryland colony, named in honor of Charles I’s consort Henrietta Maria On May 27th, 1634, Leonard Calvert and about 300 settlers arrived in the Chesapeake Bay at St. Mary’s. George Alsop published a “Land-skip” map of the new colony (1666).

But while the Calverts were settling on the Chesapeake Bay, Dutch and Swedish colonists were settling on the Delaware bay (named by Captain Thomas Argyll in honor of Lord De La Warr, the governor of the Virginia colony). At the bottom of the Delaware Bay, Dutch colonists established a settlement at Zwaanendael (now Lewes) and a trading post at Fort Nassau in 1631, although these settlers were killed in a dispute with local Indians within a year. Swedish colonists, led by Peter Minuit had purchased Manhattan Island in 1626 for the Dutch West India Company and directed the New Netherlands colony, including New Amsterdam (New York), from 1626 until 1633, when he was dismissed from the Company. He then negotiated with the Swedish government to create the New Sweden colony on the Delaware River. Minuit and a first group of Swedish colonists on two Swedish ships, the Kalmar Nyckel and the Fogel Grip, arrived at Swedes Landing in 1638 and established Fort Christina (Wilmington) as the principal town in the new colony.

The political and economic chaos of the English Civil Wars (1642-51) and the Commonwealth and Protectorate periods stalled English colonial expansion. Charles I had not called a Parliament for a decade, until the Bishops’ War in Scotland (1639) bankrupted the crown and forced him to call a new Parliament in 1640. This “Long Parliament” (which lasted eight years!) could only be adjourned by itself. Having lost control of it, Charles left London, raised a Royalist army and sought help from Scottish and Irish Catholic sympathizers. After a series of battles with Parliamentarian forces, Charles was imprisoned in 1648. The “Rump Parliament” under the control of the “New Model Army” ordered his trial for treason. He was conviced and beheaded in 1649. A Parliamentary Commonwealth (1649-53) was replaced by the Protectorate under Oliver Cromwell. After military campaigns in Scotland and Ireland, Cromwell had to deal with the first and second Dutch Wars (1652-54 and 1655-57). After Cromwell died in 1658, the army replaced his son Richard with another Parliamentary Commonwealth under a dysfunctional Rump Parliament (1659-60) before restoring the monarchy and inviting Charles II back from exile.

While England was in chaos, the Dutch kept expanding their American colonies. Colonial governor Peter Stuyvesant purchased the land between the Christina River and Bombay Hook from the Indians, and established Fort Casimir at what is now New Castle in 1651. The Swedes, just a few miles up the river, captured Fort Casimir in 1654, but Dutch soldiers from New Amsterdam (Manhattan) took control of the entire New Sweden colony in 1655.

After the Restoration brought Charles II to the English throne, English colonial expansion resumed. In 1664 the Duke of York, Charles II’s brother James, captured New Amsterdam, renaming it New York, and he seized the Swedish-Dutch colonies on the Delaware River as well. The Dutch briefly recaptured New York in 1673, but after their 1674 defeat in Europe in the third Dutch War, they ceded all their American claims to England in the Treaty of Westminster.

Having regained his American territories, the Duke of York granted the land between the Hudson and Delaware rivers to his friends George Carteret and John Berkeley in 1675, and they established the colony of New Jersey.

The Pennsylvania colony

Sir William Penn had served the Duke of York in the Dutch wars, and had loaned the crown about £16,000. His son William Penn, who had become a Quaker, petitioned Charles for a grant of land north of the Maryland colony as repayment of the debt. In 1681 Charles granted Penn all the land extending five degrees west from the Delaware River between the 40th and 43rd parallels, excluding the lands held by the Duke of York within a “twelve-mile circle” centered on New Castle, plus the lands to the south that had been ceded by the Dutch.

Was this to be a twelve-mile radius circle, or a twelve-mile diameter circle, or maybe a twelve-mile circumference circle?–—the language was uncler and unnecessary: even a twelve-mile radius circle centered on New Castle lies entirely below the 40th parallel.

The Calvert family had ample opportunity to get the 40th parallel surveyed and marked, but never bothered to do so. Philadelphia was established at the upper limit of deep-water navigability on the Delaware, although it was below the 40th parallel, and Pennsylvania colonists settled areas west and south of the city with no resistace from the Calverts.

Penn needed to get his colony better access to the Atlantic, and in 1682 he leased the Duke of York’s lands from New Castle down to Cape Henlopen. Penn arrived in New Castle in October 1682 to take official possession of the “Three Lower Counties” on the Delaware Bay. He renamed St. Jones County to Kent County, and Deale County to Sussex County, and the Three Lower Counties were annexed to the Pennsylvania colony.

Penn negotiated with the third Lord Baltimore at the end of 1682 at Annapolis, and in April 1683 at New Castle, to establish and mark a formal boundary between Maryland and Pennsylvania including the Three Lower Counties. The Calverts wanted to determine the 40th parallel by astronomical survey, while Penn suggested measuring northward from the southern tip of the Delmarva peninsula (about 370 5′ N), assuming 60 miles per degree as Charles II had suggested. (The true distance of one degree of latitude is about 69 miles.) This would have given Pennsylvania the uppermost part of the Chesapeake Bay.

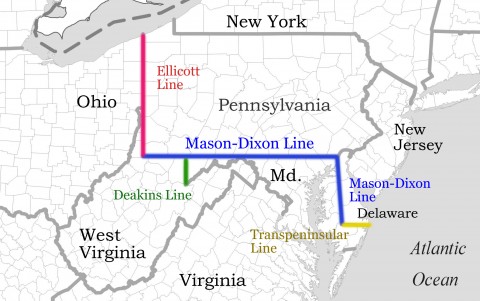

After the negotiations failed, Penn took his case to the Commission for Trade and Plantations. In 1685 the Commission determined that the land lying north of Cape Henlopen between the Delaware Bay and the Chesapeake should be divided equally; the western half belonged to the Calverts, while the eastern half belonged to the crown, i.e., to the Duke of York, and thus to Pennsylvania under Penn’s lease. So the north-south boundary between Maryland and the Three Lower Counties was now legally defined, but the east-west boundary between Pennsylvania and Maryland remained unresolved.

Charles II died in 1685, and the Duke of York, a Catholic convert, succeeded him as James II. But three years later, William of Orange, the Dutch grandson of Charles I and husband of James II’s protestant daughter Mary, seized the English throne in the “Glorious Revolution.” The Calverts lost control of their Maryland holdings, and Maryland was declared a royal colony. Penn’s ownership of Pennsylvania and the Lower Three Counties was also suspended from 1691 to 1694. The Calverts did not regain their proprietorship of Maryland until 1713 when Charles Calvert, the fifth Lord Baltimore, renounced Catholicism.

Penn revisited America in 1699-1701, and reluctantly granted Pennsylvania and the Lower Three Counties separate elected legislatures under the Charter of Privileges. He also commissioned local surveyors Thomas Pierson and Isaac Taylor to survey and demarcate the twelve-mile radius arc boundary between New Castle and Chester counties. Pierson and Taylor completed the survey in ten days using just a chain and compass. The survey marks were tree blazes, and once these disappeared, the location of the arc boundary was mostly a matter of fuzzy recall and conjecture.

Geodetic science was in its infancy. Latitude could be estimated reasonably accurately with sextant and compass, but longitude was largely guesswork. As England’s naval power and colonial holdings continued to expand, the demand for better maps and navigation intensified. Parliament set a prize of £20,000 for a solution to the “longitude problem” in 1712. The challenge was to determine a longitude in the West Indies onboard a ship with less than half a degree of longitude error. Dava Sobel’s book Longitude (1996) details how clock-maker John Harrison eventually won the prize with his “H4” precision chronometer.

Penn died in 1718, disinheriting his alcoholic eldest son William Jr., and leaving the colonies to his second wife Hannah, who transferred the lands to her sons Thomas, John, Richard and Dennis. Thomas outlived the others and accumulated a two-thirds interest in the holdings.

In 1731, the fifth Lord Baltimore petitioned King George II for an official resolution of the boundary dispute. In the ensuing negotiations the Calverts tried to hold out for the 40th parallel, but Pennsylvania colonists had settled enough land to the west and southward of Philadelphia that this was no longer practical. In 1732 the parties agreed that the boundary line should run east from Cape Henlopen to the midpoint of the peninsula, then north to a tangency with the west side of the twelve-mile radius arc around New Castle, then around the arc to its northernmost point, then due north to an east-west line 15 miles south of Philadelphia. It was a bad deal for the Calverts. The east-west line would turn out to be about 19 miles south of the 40th parallel, and, as the map appended to the agreement shows (Senex, 1732), would intersect the arc. The map placed “Cape Hinlopen” at what is now Fenwick Island, almost 20 miles to the south as well; this error was an attempt at deception, not ignorance (compare the 1670 map from more that 50 years earlier). But litigation over interpretation and details dragged on.

The border conflict led to sporadic local violence. In 1736 a mob of Pennsylvanians attacked a Maryland farmstead. A survey party commissioned by the Calverts was run off by another mob in 1743.

In 1750, the Court of Chancery established a bipartisan commission to survey and mark the boundaries per the 1732 agreement. The commissioners hired local surveyors to mark an east-west transpeninsular line from Fenwick Island to the Chesapeake in 1750-51, and then determine the middle point of this line, which would mark the southwest corner of the Three Lower Counties. As the survey team worked from Fenwick Island westward the rivers, swamps and dense vegetation made the work difficult, and there were continuing disputes, e.g., should distances be determined by horizontal measures or on the slopes of the terrain? Should the transpeninsular line stop at the Slaughter Creek estuary or continue across that peninsula, known as Taylor’s Island, to the open Chesapeake? Should the line stop at the inundated marsh line of the Chesapeake or at open water?

The transpeninsular survey and its middle point were not officially approved in London until 1760. In 1761, the colonial surveyors began running the north-south “tangency” line from the middle point toward a target tangent point on the twelve-mile arc. With poor equipment and some miscalculations, their first try at a tangency line passed a half-mile east of the target point on the arc. Their second try was 350 yards to the west. The disputants required much higher standards of accuracy, and they consulted the royal astronomer James Bradley at the Greenwich observatory for advice on getting the survey done right.

The Mason and Dixon survey

Bradley recommended Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon to complete the boundary survey. Mason was Bradley’s assistant at the observatory, an Anglican widower with two sons. Dixon was a skilled surveyor from Durham, a Quaker bachelor whose Meeting had ousted him for his unwillingness to abstain from liquor. In 1761 Mason and Dixon had sailed together for Sumatra, but only made it to the Cape of Good Hope, to record a transit of Venus across the sun to support the Royal Society’s calculations of distance by parallax between the Earth and sun. Their major tasks in America would be to survey the exact tangent line northward from the middle point of the transpeninsular line to the twelve-mile arc, and survey the east-west boundary five degrees westward along a line of latitude passing fifteen miles south of the southernmost part of Philadelphia (Figure 6). It would be one of the great technological feats of the century

Mason and Dixon arrived in Philadelphia on November 15th 1763 during a tense period. The Seven Years’ War had spilled over to North America as the French and Indian Wars, and although the Treaty of Paris, signed in February 1763, had put an official end to the hostilities, conflicts between colonists and Indians continued. The Iroquois League, or Six Nations (Mohawk, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, Oneida and Tuscarora), had supported the British against their longtime enemies, the Cherokee, Huron, Algonquin and Ottawa, whom the French had supported in their attacks on colonists. Pontiac, chief of the Ottawa, had organized a large-scale attack on Fort Detroit on May 5th 1763, and some 200 settlers were massacred along the western frontier.

Local reaction to the news was brutal. In Lancaster, Pennsylvania, a mob of mostly Scots-Irish immigrants known as the “Paxton boys” attacked a small Conestoga Indian village in December, hacked their victims to death and scalping them. The remaining Conestogas were brought to the town jail for protection, but when the mob attacked the jail the regiment assigned to protect the Indians did nothing to stop them. The helpless Indians—men, women and children—were all hacked to pieces and scalped in their cells. The Paxton Boys then went after local Moravian Indians, who were taken to Philadelphia for protection. Enraged that the government would “protect Indians but not settlers,” about 500 Paxton Boys actually invaded Philadelphia on February 6, 1764, although Benjamin Franklin was able to calm the mob. Mason and Dixon were shocked at the violence, and Mason would visit the scene of the Lancaster murders a year later. As the survey progressed, racial violence and the relentless dispossession of Indians were frequent background themes.

Mason had brought along state-of-the-art equipment for the survey. This included a “transit and equal altitude instrument,” a telescope with cross-hairs, mounted with precision adjustment screws, to sight exact horizontal points using a mounted spirit level, and also to determine true north by tracking stars to their maximum heights in the sky where they crossed the meridian. The famous “zenith sector,” built by London instrument-maker John Bird, was a six-foot telescope mounted on a six-foot radius protractor scale, with fine tangent screws to adjust its position; it was used to measure the angles of reference stars from the zenith of the sky as they crossed the meridian. These measurements could be compared against published measurements of the same stars’ angles of declination at the equator to determine latitude. These were more reliable than measurements of azimuth against a plumb bob, which were already known to be subject to local gravitational anomalies. The zenith sector traveled on a mattress laid on a cart with a spring suspension.

Mason and Dixon also brought a Hadley quadrant, used to measure angular distances; high-quality survey telescopes; 66-foot long Gunter chains comprised of 100 links each (1 chain = 4 rods; 1 chain × 10 chains = 43,560 square feet = 1 acre; 80 chains = 1 mile), along with a precision brass measure to calibrate the chain lengths; and wood measuring rods or “levels” to measure level distances across sloping ground. A large wooden chest contained a collection of star almanacs, seven-figure logarithm tables, trigonometric tables and other reference materials; Mason was skilled at spherical trigonometry.

Mason had acquired a precision clock so that the local times of predicted astronomical events could be compared against published Greenwich times. Each one-minute local time difference implies a 15-second longitude difference. John Harrison’s “H4” chronometer had sailed to Jamaica and back in 1761, losing only 39 seconds on the round trip; the longitude calculations in Jamaica based on his clock were well within the accuracy standards Parliament had set for the £20,000 longitude prize. But Nevil Maskelyne, who had succeeded Bradley as royal astronomer, and the Royal Society remained skeptical about the reliability of chronometers in complementing astronomical calculations of longitude. Maskelyne insisted on the superiority of a purely astronomical approach, a computationally complex “lunar distance” method based on angular distances between the moon and various reference stars. Harrison wouldn’t collect his entire prize until 1773. Mason and Dixon would test the reliability of chronometric positioning, although Mason was skeptical of it.

The southernmost part of Philadelphia was determined by the survey commissioners to be the north wall of a house on the south side of Cedar Street (the address is now 30 South Street) near Second Street. Mason and Dixon had a temporary observatory erected 55 yards northwest of the house, and after detailed celestial observations and calculations, they determined the latitude of the house wall to be 39o56’29.1″N.

Since going straight south would take them through the Delaware River, they then surveyed and measured an arbitrary distance (31 miles) west to a farm owned by John Harland in Embreeville, Pennsylvania, at the “Forks of the Brandywine.” They negotiated with Harland to set up an observatory, and set a reference stone, now known as the Stargazer’s Stone, at the same latitude. They spent the winter at Harland’s farm making astronomical observations on clear nights and enjoying local taverns on cloudy nights. The Harland house still stands at the intersection of Embreeville and Stargazer Roads, and the Stargazers’ Stone is in a stone enclosure just up Stargazer Road on the right. Its latitude is 39o56’18.9″N, which they calculated to be 356.8 yards south of the parallel determined in Philadelphia.

At Harland’s they observed and timed predicted transits of Jupiter’s moons, as well as a lunar eclipse on March 17th 1764. The average (sun) time of these events at the Stargazers’ Stone was 5 hours 12 minutes and 54 seconds earlier than published predicted times for the Paris observatory (longitude 2o20’14″E). So they were able to estimate their longitude as (5:12:54)/(24:00:00) x 360o = 78o13’30″west of Paris, and thus 78o13’30″ – 2o20’14″ = 75o53’6″ west of Greenwich. They published these findings in the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions in 1769.

The clock used in this experiment was actually 37 seconds fast, so at fifteen arc seconds of longitude per clock second, their calculated longitude was 9’15″ or about eight miles too far west. That was more accurate than Parliament’s longitude prize had required, but the margin of error was still a thousand times larger than the margin of error in their latitude calculations. Fortunately, Mason and Dixon’s principal tasks involved more local positioning than global positioning. They proposed measuring a degree of longitude for the Royal Society as part of their survey of the parallel between Pennsylvania and Maryland; although the Society never funded that project, it would fund their measurement of a degree of latitude in 1768.

In the spring of 1764 the survey party ran a line due south from Harland’s farm, measured with the survey chains and levels, with a team of axmen clearing a “visto” or line of sight eight or nine yards wide the entire way. They arrived in April 1764 at a farm field owned by Alexander Bryan in what is now the Possum Hill section of Delaware’s White Clay Creek State Park. They placed an oak post called “Post mark’d West” at a latitude of 39o43’ 26.4″N, after verifying that this point was exactly 15 miles below the 39o56’29.1″N latitude they had determined in Philadelphia. This point is now marked by a stone monument accessible by a short spur trail off the Bryan’s Field trail, about 600 yards downhill (due south) from the ruins of the farmstead. The easiest access point is from the east (gravel road) parking lot at Possum Hill off Paper Mill Road. The Post mark’d West would be the eastern origin and reference latitude point for the west line.

Mason and Dixon then headed south to the middle point of the transpeninsular line that the colonial surveyors had marked, and they spent the rest of 1764 surveying the north-south boundary line. With a team of axmen clearing the vistos ahead of them, they resurveyed and marked the tangency line northward from the middle point toward the target tangency point on twelve-mile arc 82 miles to the north. They crossed the Nanticoke River, Marshyhope Creek, Choptank River, Bohemia River, and Broad Creek. Where their survey chains could not span a river, they measured the river width by triangulation, using the Hadley quadrant on its side to calculate the angle between two points on the opposite side. They arrived at the 82-mile point in August 1764.

Mason and Dixon then ran an exact twelve-mile line from the New Castle courthouse to the tangency line, setting the tangent point marker at the 82-mile point of the tangency line; this is located by a small drainage pond at the edge of an apartment complex, about 600 meters south of the Delaware-Maryland boundary on Elkton Road, about 100 meters north of the rail lines. It was 17 chains and 25 links west of the tangency point targeted by the 1761 survey. Since the tangency line runs slightly west of true north, the tangent point lies south and slightly east of the arc’s westernmost point.

After joining the tangency line perpendicularly to the twelve-mile radius line from New Castle in August 1764, they returned south to the middle point, checking and correcting marks as they went. On this re-check, their final error at the middle point, after 82 miles, was 26 inches. They returned north again, making final placements of the marks into November. During this phase of the survey, their base of operations in Delaware was St. Patrick’s Tavern in Newark, where the Deer Park Tavern now stands. Tavern scenes in Thomas Pynchon’s 1997 novel Mason & Dixon are consistent with at least one contemporary account of their enjoyment of the taproom. In January 1765 Mason visited Lancaster (and the jail where the Tuscaroras had been slaughtered) and “Pechway” (Pequa). In February, he toured Princeton NJ and New York.

Mason and Dixon began the survey of the west line from the “Post mark’d West” in April 1765. The Arc Corner Monument, located at the north side of the W.S. Carpenter Recreation Area of White Clay Creek State Park, just off Hopkins Bridge Road, marks the intersection of the west line with the 12-mile arc, and is the start of the actual Maryland-Pennsylvania boundary line. Mason and Dixon spent the next couple of years surveying this line westward. Again, their axmen cleared vistos, generally eight yards wide. They would survey straight 12-mile line segments, starting at headings about 9 minutes northward of true west and sighting linear chords to the true latitude curve, then make detailed astronomical calculations to adjust the intermediate mile mark southward to the exact 39o 43’ 17.4″ N latitude. The true latitude is not a straight line: looking westward in the northern hemisphere it gradually curves to the right. It was exacting work.

The survey crossed the two branches of the Christina Creek, the Elk River, and the winding Octoraro several times. The survey party reached the Susquehanna in May 1765.

At the end of May they interrupted the survey of the west line, and returned to Newark to survey the north line from the tangent point through the western edge of the 12-mile arc to its intersection with the west line. From the tangent point, the survey proceeded due north, intersecting the arc boundary again about a mile and a half further up at a point now marked by an “intersection stone.” The location is behind the DuPont Company’s Stine-Haskell labs north of Elkton Road very near the Conrail rail line. The north line ended at a perpendicular intersection with the west line in a tobacco field owned by Captain John Singleton. This is the northeast corner of Maryland.

The boundaries between Maryland and the Three Lower Counties were now complete. The locations of the final mile points on the tangent and north lines, and the discernible inflections of the Maryland/Delaware boundary at the tangent point, are shown on the Newark West 7.5-minute USGS topographic map. The tri-state marker is located about 150 meters east of Rt. 896 behind a blue industrial building at the MD/PA boundary. The thin sliver of land (secant) west of the North Line but within the 12-mile arc west of the North Line was assigned to New Castle County (PA, now DE) per the 1732 agreement. The “Wedge” between the North Line and the 12-mile arc just below the West Line was assigned to Chester County, PA, but later ceded to Delaware.

In June 1765 Mason and Dixon reported their progress to the survey commissioners representing the Penn and Calvert families at Christiana Bridge (now the village of Christiana). They then resumed the survey of the west line from the Susquehanna. As they went along, the locals learned whether they were Marylanders or Pennsylvanians. They reached South Mountain (mile 61) at the end of August, crossed Antietam Creek and the Potomac River in late September, and continued westward to North (aka Cove) Mountain near Mercersburg PA in late October, completing a total of 117 miles of the west line that year. From the summit of North Mountain they could see that their west line would pass about two miles north of the northernmost bend in the Potomac. Had the Potomac looped further north into Pennsylvania, the western piece of Maryland would have been cut off from the rest of the colony.

The survey party stored their instruments at the house of a Captain Shelby near North Mountain, and returned east in the fall, checking and resetting their marks. In November 1765 they returned to the middle point to place the first 50 mile markers along the tangent line. These had been quarried and carved in England, and were delivered via the Nanticoke and Choptank rivers. They spent January 1766 at the Harland farm. In February and March, Mason traveled “for curiosity” to York PA; Frederick MD; Alexandria, Port Royal, Williamsburg and Annapolis VA.

The survey party rendezvoused at North Mountain in March 1766 and resumed the survey from there, reaching Sideling Hill at mile 135 at the end of April. There were long periods of rain and snow through late April. West of Sideling Hill was almost unbroken wilderness, and the wagons with the marker stones couldn’t make it over the mountain so they marked with oak posts from there onward. They reached mile 165 in June, near the eastern continental divide, and spent the rest of the summer backtracking for corrections and final placement of marks. Mason noted the gradual curvature of the visto along the latitude, as seen from several summits including the top of South Mountain:

From any Eminence in the Line where 15 or 20 Miles of the Visto can be seen (of which there are many): The said Line or Visto very apparently shows itself to form a Parallel of Northern Latitude. The Line is measured Horizontal; the Hills and Mountains measured with a 16 ½ feet Level and besides the Mile Posts; we have set Posts in the true Line, marked W, on the West side, all along the Line opposite the Stationary Points where the Sector and Transit Instrument stood. The said Posts stand in the Middle of the Visto; which in general is about Eight yards wide. The number of Posts set in the West Line is 303. (Journal entry for 25 September 1766)

Back in Newark in October, they got permission from the commissioners to measure the distance of a degree of latitude as a side project for the Royal Society. They returned to the middle point of the transpeninsular line for astronomical observations in preparation for this, then returned to Newark and began setting 100 stone mile markers along tangent and west lines. The stones in the west line were set at mile intervals starting from the northeast corner of Maryland. At the end of November, at the request of the commissioners, they measured the eastward extension of the west line from the Post mark’d West across Pike, Mill, Red Clay and Christiana (Christina) creeks to the Delaware River. The southern boundary of Pennsylvania was to extend 5 degrees of longitude west from this point.

They spent parts of the winter of 1766-67 at Harland’s farm making astronomical observations, using a clock on loan from the Royal Society to time ephemera. Mason spent the late winter and early spring traveling through Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia. He met the chief of the Tuscaroras in Williamsburg.

The survey was supposed to extend a full five degrees of longitude (about 265 miles) to the west, but the Iroquois wanted the survey stopped. Negotiations between the Six Nations and William Johnson, the commissioner of Indian Affairs, lasted well into 1767. After a payment of £500 to the Indians, Mason and Dixon finally got authorization in June 1767 to continue the survey from the forks of the Potomac near Cumberland. They started out with more than 100 men that summer, including an Indian escort party and a translator, Hugh Crawford, as they continued the survey westward from mile 162.

A.H. Mason’s edition of the survey journal (1969) includes a long undated memorandum written by Mason describing the terrain crossed by the west line. West of the Monongahela they met Catfish, a Delaware; then a party of Seneca warriors on a raid against the Cherokees; then Prisqueetom, an 86-year-old Delaware who “had a great mind to go and see the great King over the Waters; and make a perpetual Peace with him; but was afraid he should not be sent back to his own Country.” The memorandum includes Crawford’s detailed descriptions of the Allegheny, Ohio and Mississippi rivers and many of their tributaries.

As the survey party opened the visto further westward, the Indians grew increasingly resentful of the intrusion into their lands. The survey team reached mile 219 at the Monongahela River in September. Twenty-six men quit the crew in fear of reprisals from Indians, leaving only fifteen axmen to continue clearing vistos for the survey until additional axmen could be sent from Fort Cumberland. On October 9th, 231 miles from the Post mark’d West, the survey crossed the Great Warrior Path, the principal north-south Indian footpath in eastern North America. The Mohawks accompanying the survey said the warpath was the western extent of the commission with the chiefs of the Six Nations, and insisted the survey be terminated there. Realizing they had gone as far as they could, Mason and Dixon set up their zenith sector and corrected their latitude, and backtracked about 25 miles to reset their last marks. They left a stone pyramid at the westernmost point of their survey, 233 miles 17 chains and 48 links west of the Post mark’d West in Bryan’s field.

Mason and Dixon returned east, arriving back at Bryan’s farm on December 9th 1767, and reported their work to the commissioners at Christiana Bridge later that month. They had hoped the Royal Society would sponsor a measurement of a degree of longitude along the west line, but that proposal was never approved. Mason calculated that if the earth were a perfect spheroid of uniform density (which it is not) the measurement would be 53.5549 miles.

They spent about four months in early 1768 working on the latitude measurement project for the Royal society, using high-precision measuring levels with adjustments for temperature. They worked their way southward from the tangent point reaching the middle point in early June 1768, then working northward again. In Mason’s final calculation, published in the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions in 1768, a degree of latitude on the Delmarva Peninsula from the middle point northward was 68.7291 miles.

On August 16th 1768 they delivered 200 printed copies of the map of their surveys, as drawn by Dixon, to the commissioners at a meeting at New Town on the Chester River. They were elected to the American Philosophical Society in April 1768. After settling their accounts, they enjoyed ten days of socializing in Philadelphia and then left for New York, sailing on the Halifax Packet to Falmouth, England, on September 11th 1768.

Dixon was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1773. He remained a bachelor, retired to Cockfield, Durham, and died in 1779 at age 45.

Mason remarried in 1770, and continued to work for Nevil Maskelyne at the Royal Observatory, although he was never elected to the Royal Society. He returned to Philadelphia with his second wife and eight children in July 1786, died there on October 25th, and was buried in the Christ Church burial ground on Arch Street. His widow and her six children returned to England. His two sons from his first marriage remained in America.

Less than a decade after the 1763-67 survey settled their long-running boundary dispute, the Penns and Calverts lost their colonies to the American Revolution. On June 15, 1776, the “Assembly of the Lower Counties of Pennsylvania” declared that New Castle, Kent and Sussex Counties would be separate and independent of both Pennsylvania and Britain. So Mason and Dixon’s tangent, north and west lines became the boundaries between the three new states of Delaware, Maryland and Pennsylvania.

The Mason-Dixon Line

The west line would not become famous as the “Mason-Dixon Line” for another fifty years as America slowly and haltingly addressed longstanding inequities in civil rights.

In the east, the piedmont Lenni Lenape tribes of Delaware and Pennsylvania were completely dispossessed, and the remnants of the tribes were eventually relocated by a series of forced marches: to Ohio, Indiana, Missouri, Kansas, and finally to the Indian Territory which became Oklahoma. Hannah Freeman (1730-1802), known as “Indian Hannah,” was the last of the Lenni Lenape in Chester County, Pennsylvania.

The tidewater Nanticoke communities were dispersed from Delaware and Maryland by 1750, and the last tribal speaker of the Nanticoke, Lydia Clark, died before 1850. Some migrated as far north as Canada and were assimilated into other tribes, and some were relocated west. The remnant that remains in the area holds an inter-tribal pow-wow each September in Sussex County.

With Indians almost entirely displaced from the eastern states, the national debate focused on slavery and abolition, and whether new states entering the Union should be free or slave states. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 designated Mason and Dixon’s west line as the national divide between the “free” and “slave” states east of the Ohio River, and the line suddenly acquired new significance.

Delaware’s 1776 state constitution had banned the importation of slaves, and state legislation in 1797 effectively stopped the export of slaves by declaring exported slaves automatically free. The state’s population in the 1790 census was 15 percent black, and only 30 percent of these were free blacks. By the 1820 census, 78 percent of Delaware’s blacks were free. By 1840, 87 percent were free.

Both escaped slaves and legally free blacks living anywhere near the line were vulnerable to kidnapping by slave-catchers operating out of Maryland. One of the most famous kidnappers was Patty Cannon, a notoriously violent woman who, with her son-in-law Joe Johnson, ran a tavern on the Delaware-Maryland line near the Nanticoke River. The Cannon-Johnson gang seized blacks as far north as Philadelphia and transported them south for sale, hiding them in her house or supposedly shackled to trees on a small island in the Nanticoke River, and then transporting across the Woodland ferry or loading them onto a schooner to be shipped down the Nanticoke for eventual sale in Georgia. In 1829 Cannon and Johnson were arrested and charged with kidnapping, and Cannon was charged with several murders, including the murder of a slave buyer for his money. Johnson was flogged, and Cannon died in jail before trial, reportedly a suicide by poison. Her skull is kept in a hatbox at the Dover Public Library. It does not circulate via inter-library loan.

For free blacks in Delaware, freedom was quite restricted. Blacks could not vote, or testify in court against whites. After Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion in Virginia triggered rumors and panic about a black insurrection in Sussex County, the Delaware legislature banned blacks from owning weapons, or meeting in groups larger than twelve.

Through the first half of the 19th century the Mason-Dixon Line represented the line of freedom for tens of thousands of blacks escaping slavery in the south. The Underground Railroad provided food and temporary shelter at secret way-stations, and guided or sometimes transported northbound slaves across the Line. The spirituals sung by these slaves included coded references for escapees: the song “Follow the drinking gourd” referred to the Big Dipper from which runaways could sight the North Star; the River Jordan was the Mason-Dixon Line; Pennsylvania was the Promised Land. After the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 allowed slave owners to pursue their escaped slaves into the north, the line of freedom became the Canadian border, “Canaan” in the spirituals, and abolitionists created Underground Railroad stops all the way to Canada.

Thomas Garrett, a member of Wilmington’s Quaker community, was one of the most prominent conductors on the Underground Railroad. In 1813, while Garrett was still living in Upper Darby, Pennsylvania, a free black employee of his family’s was kidnapped and taken into Maryland. Garrett succeeded in rescuing her, but the experience reportedly made him a committed abolitionist, and he dedicated the next fifty years of his life to helping others escape slavery.

Garrett moved to Wilmington in 1822 and lived at 227 Shipley Street, where he ran a successful iron business. He befriended and helped Harriet Tubman as she brought group after group of escaping slaves over the line; his house was the final step to freedom. Garrett was caught in 1848, prosecuted and convicted, forthrightly telling the court he had helped over 1,400 slaves escape. Judge Roger Taney ordered Garrett to reimburse the owners of slaves he was known to have helped, and it bankrupted him, but he continued in his work, assisting approximately 1,300 more slaves to freedom by 1864. Taney went on to become Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court, and wrote the majority decision in Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857), declaring that no blacks, slave or free, could ever be US citizens, and striking down the Missouri Compromise.

In the buildup to the Civil War, Delaware was a microcosm of the country, sharply split between abolitionists in New Castle County and pro-slavery interests in Sussex County. A series of abolition bills were defeated in the state legislature by a single vote. Like other Union border states, Delaware remained a slave state during the war, although its slave population had fallen to only a few hundred. President Abraham Lincoln offered a federal reimbursement of $500 per slave (far more than their market value) to Delaware slave-owners if Delaware would abolish slavery, but the state legislature stubbornly refused.

Lincoln’s January 1st 1863 Emancipation Proclamation abolished slavery in the Confederate states, but not in the Union border states. After the Civil War, Maryland, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri and Arkansas outlawed slavery on or before their individual ratifications of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. New Jersey had technically abolished slavery in 1846, although it only ratified the Amendment in 1866. So as the Thirteenth Amendment neared ratification by 27 of the 36 states on December 6th 1865, America’s last two remaining slave states were Kentucky and Delaware. Delaware didn’t ratify the Thirteenth, Fourteenth or Fifteenth amendments until 1901.

In the middle of the 20th century the Mason-Dixon Line was the backdrop for one of the five school desegregation cases that were eventually consolidated into the US Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka case. Until 1952, public education in Delaware was strictly segregated. Since the late 19th century, property taxes paid by whites in Delaware had funded whites-only schools, while property taxes paid by blacks funded blacks-only schools. In the 1910’s, P.S. duPont had financed the construction of schools for black children throughout Delaware, and effectively shamed the Legislature into providing better school facilities for whites as well. There was only high school for black children in the entire state—Howard High School. Persistent income disparities between blacks and whites insured persistent inequalities in public education. In 1950 the Bulah family had a vegetable stand at the corner of Valley Road and Limestone Road, and Shirley Bulah attended Hockessin Colored Elementary School 107, which had no bus service. The bus to Hockessin School 29, the white school, went right past the Bulah farm, and the Bulahs merely asked if Shirley could ride the bus to her own school. But Delaware law prohibited black and white children on the same school bus.

Shirley’s mother Sarah Bulah contacted Wilmington lawyer Louis Redding, who had recently won the Parker v. University of Delaware case forcing the University to admit blacks. In 1950, the Wilmington chapter of the NAACP had launched an effort to get black parents in and around Wilmington to register their children in white schools, but the children were turned away. Redding chose the Bulahs as plaintiffs in one of two test cases, and convinced Sarah Bulah to sue in Delaware’s Chancery Court for Shirley’s right to attend the white school (Bulah v. Gebhart). Parents of eight black children from Claymont filed a parallel suit (Belton v. Gebhart). The complaints argued that the school system violated the “separate but equal” clause in Delaware’s Constitution (taken from Plessy v. Ferguson) because the white and black schools clearly were not equal.

Redding knew that a court venue on the Mason-Dixon Line, with its local legacies of slavery and abolitionism, would be most likely to support integration. He argued the cases pro bono and the Wilmington NAACP paid the court costs. In 1952, Judge Collins Seitz found that the plaintiffs’ black schools were not equal to the white schools, and ordered the white schools to admit the plaintiff children. The Bulah v. Gebhart decision did not challenge the “separate but equal” doctrine directly, but it was the first time an American court found racial segregation in public schools to be unconstitutional. The state appealed Seitz’s decision to the Delaware Supreme Court, where it was upheld. The state’s appeal to the US Supreme Court was consolidated into the Brown v. Board case, which also upheld the decision.

The town of Milford, Delaware, had riots when it integrated its schools immediately after the Brown decision. Elsewhere in Delaware, school integration proceeded slowly; the resistance to it was passive but pervasive. A decade after Brown, Delaware still had seventeen blacks-only school districts. As Wilmington’s schools were integrated, upscale families, both black and white, were moving to the suburbs, leaving behind high-poverty, black-majority city neighborhoods. Wilmington’s public school system, now serving a predominantly black, low-income population, was mired in corruption and failure.

Following a second round of civil rights litigation in the 1970’s, the US Third Circuit court imposed a desegregation plan on New Castle County in 1976, under which schools in Wilmington would teach grades 4, 5 and 6 for all children in the northern half of the county, while suburban schools would teach grades 1-3 and 7-12. Wilmington children would have nine years of busing to the suburbs; suburban children would have three years of busing to Wilmington. After the 1976 desegregation order, a spate of new private schools popped up in the suburbs. One third of all schoolchildren living within four districts around Wilmington now attend non-public schools.

In 1978 the Delaware legislature split the northern half of New Castle County into four large suburban districts, each to include a slice of Wilmington. The Brandywine, Red Clay Consolidated and Colonial districts are contiguous to Wilmington and serve adjacent city neighborhoods. The Christina district has two non-contiguous areas: the large Newark-Bear-Glasgow area and a high-poverty section of Wilmington about 10 miles distant on I-95.

In 1995, the federal court lifted the desegregation order, declaring that the county had achieved “unitary status.” Wilmington’s poorest communities remain predominantly black, but the urbanized Newark-New Castle corridor now has far more minority households than Wilmington. The school districts are committed to reducing black-white school achievement gaps as mandated under the federal No Child Left Behind Act (the 2000 reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act).

Louis Redding and Collins Seitz both died in 1998. The city government building at 800 North French St. in Wilmington is named in Redding’s honor.

Miscellany

The 800-acre triangular area known as the Wedge lies below the eastern end of Mason and Dixon’s West line, bounded by Mason and Dixon’s North line on the west and the 12-mile arc on the east. It is located west of Wedgewood Road, and is intersected by Rt. 896 in Delaware just before the road crosses the very northeast tip of Maryland into Pennsylvania. Although the Delaware legislature had representatives from the Wedge in the mid-19th century, jurisdiction over the Wedge remained ambiguous. A joint Delaware-Pennsylvania commission assigned it to Delaware in 1889, and Pennsylvania ratified the assignment in 1897, but Delaware, sensitive to Wedge residents who considered themselves Pennsylvanians, didn’t vote accept the Wedge as part of Delaware until 1921. Congress ratified the compact in 1921.

Through most of the 19th century the Wedge was a popular hideout for criminals, and a place for duels, prize-fighting, gambling and other recreations, conveniently outside any official jurisdiction. A historic marker on Rt. 896 summarizes its history. An 1849 stone marker replaced the stone Mason and Dixon used to mark the intersection of the North line with the West line; when the Wedge was annexed to Delaware in 1921 this became the MD/PA/DE tri-state marker.

Until fairly recently, the area around Rising Sun, Maryland, had sporadic activity from a local Ku Klux Klan group whose occasional requests for parade permits attracted a lot of media attention. In his book Walkin’ the Line, William Ecenbarger recounts watching a Klan rally in Rising Sun 1995. Local Klan leader Chester Doles served a prison sentence for assault, and then left Cecil County for Georgia. Whatever Klan is left in this area has been very quiet since.

The Mason-Dixon Trail is a 193-mile hiking trail, marked in light blue paint blazes. It begins at the intersection of Pennsylvania Route 1 and the Brandywine River in Chadds Ford, PA; runs southeast through Hockessin and Newark, DE; eastward though Elkton to Perryville and Havre de Grace, MD (although pedestrians are not allowed on the Rt. 40 bridge!); then northward up the west side of the Susquehanna into York County, PA, and proceeding northwest through York County through Gifford Pinchot State Park to connect with the Appalachian Trail at Whiskey Springs. The Mason-Dixon Trail does not actually follow any line that Mason and Dixon surveyed, but it’s an interesting trail over diverse terrain.

The stone markers used in the Mason-Dixon survey were quarried and carved in England and shipped to America. The ordinary mile markers placed by the survey party are inscribed with “M” and “P” on opposite sides. Every fifth mile was marked with a crownstone with the Calvert and Penn coats of arms on opposite sites. The locations of many of these markers are noted on USGS 7.5-minute topographic maps. Roger Nathan and William Ecenbarger have both explored these markers and written readable histories of them. Many markers are lost, but some are still accessible (with landowner permission).

Bibliography

Cope, Thomas D. 1949. Degrees along the west line, the parallel between Maryland and Pennsylvania. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 93(2):127-133 (May 1949). Thomas Cope, a physics professor at the University of Pennsylvania, published a number of articles about the survey.

Cummings, Hubertis Maurice, 1962. The Mason and Dixon line, story for a bicentenary, 1763-1963. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Dept. of Internal Affairs, Harrisburg, PA. Written for the bicentennial of the survey, this book provides a good mix of technical detail and narrative.

Danson, Edwin, 2001 Drawing the line : How Mason and Dixon surveyed the most famous border in America. John Wiley & Sons, New York. Provides the clearest technical explanations of the survey along with a readable narrative of it.

Ecenbarger, William, 2000. Walkin’ the line: a journey from past to present along the Mason-Dixon. M. Evans, New York. Ecenbarger describes his tour of the tangent, north and west lines, and intertwines local vignettes of slavery and civil rights with brief descriptions of the actual survey.

Latrobe, John H. B. 1882. “The history of Mason and Dixon’s line” contained in an address, delivered by John H. B. Latrobe of Maryland, before the Historical society of Pennsylvania, November 8, 1854. G. Bower, Oakland, DE.

Mason, A.H. (ed.) Journal of Charles Mason [1728-1786] and Jeremiah Dixon [1733-1779]. 1969. Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society vol. 76). American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia. The survey journal, written in Mason’s hand, was lost for most of a century, turning up in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1860; the original is now in the National Archives in Washington DC. A transcription edited by A. Hughlett Mason was published in 1969 by the American Philosophical Association. The journal is mostly technical notes of the survey, with letters received and comments by Mason on his travels interspersed. An abridged fair copy of the journal, titled “Field Notes and Astronomical Observations of Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon,” is in Maryland’s Hall of Records in Annapolis.

Nathan, Roger E. 2000. East of the Mason-Dixon Line: a history of the Delaware boundaries. Delaware Heritage Press, Wilmington, DE. Focuses on the history of Delaware’s boundaries, in which Mason and Dixon played the largest part.

Pynchon, Thomas. 1997. Mason & Dixon. Henry Holt, New York. Pynchon’s novel mixes historically accurate details with wild fantasies. Mason and Dixon are portrayed as naïve, picaresque characters, the Laurel and Hardy of the 18th century, surrounded by an odd cast including a talking dog, a mechanical duck in love with an insane French chef, an electric eel, a renegade Chinese Jesuit feng-shui master, and a narrator who swallowed a perpetual motion watch. Mason and Dixon personify America’s confused moral compass, slowly realizing how their survey line defiles a wild, innocent landscape, and opens the west to the violence and moral ambiguities that accompany “civilization.”

Sobel, Dava. 1996. Longitude: the true story of a lone genius who solved the greatest scientific problem of his time. Walker & Co., New York.