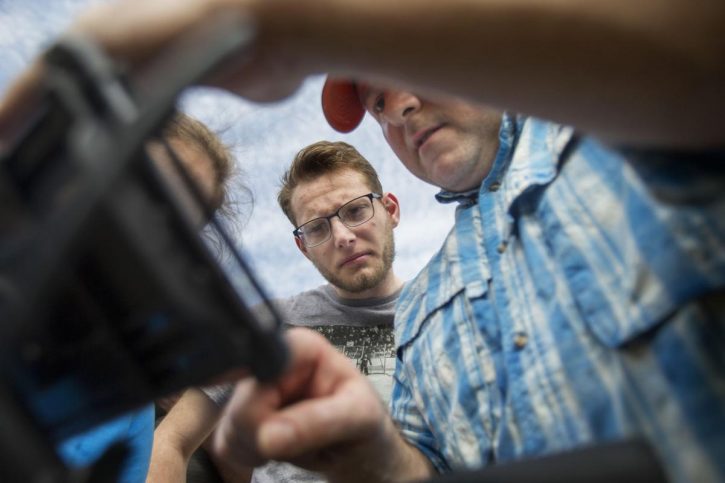

Jon Marcoux, director of historic preservation at Clemson Design Center, scans the grounds of Marion Square for traces of “Horn Works” on Wednesday Feb. 5, 2020, in Charleston. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

The ugly slab of shell-spackled rock in Marion Square was once a piece of an intimidating tabby fort that stood like the battlements of a castle in front of the British attacking Charleston during the Revolutionary War.

The so-called “Horn Work” was a walled-off, moated, 8-acre bulwark that held 18 of the Americans’ largest guns behind a gate wide enough that Gen. William Moultrie rode through at a full gallop.

The works might easily be the largest tabby fort ever built.

But nobody knows, yet.

That’s why Clemson Design Center and College of Charleston students are in Marion Square this week rolling ground-penetrating radar trying to ping buried rock slabs or the leftover remains of the fort’s foundation.

The goal is to pinpoint where and how big the defense was while helping to better understand its signature role in the history of the city using interpretative markers and augmented reality re-creations.

“Huge, impressive, intimidating, the structure literally guarded the entrance to Charleston,” said historian Nic Butler, who has pushed for the overdue recognition.

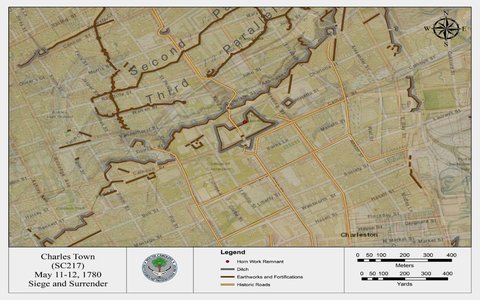

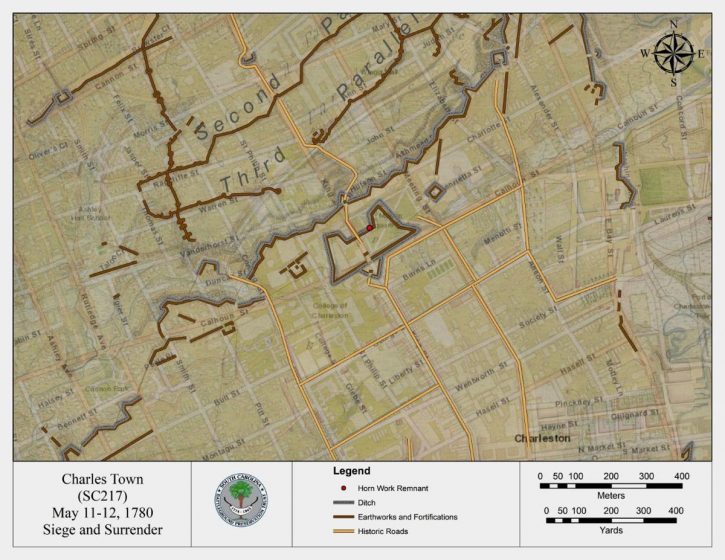

The Horn Work straddled today’s King Street, which 250 years ago was the only road into the city. It went from Marion Square to the Francis Marion Hotel and adjoining garage. Its rear wall likely abutted today’s Calhoun Street. Its name came from two protruding points that faced north, putting soldiers on walls to either side of people entering the gate hoping to pass south on King.

It withstood attacks during the 1780 Siege of Charleston. One eyewitness characterized the gunfire as devastating to British soldiers. The city, though, surrendered after a bombardment by British guns.

The walls stood for only 30 years, knocked down likely to fill the moat with the debris.

Today the lone slab is all that remains above ground, with a simple marker that reads “Remnant of Horn Work.”

“Visitors come (and) see this ugly piece of rock and say, ‘I don’t care,’ ” Butler said.

Others, though, boast of its significance.

“Nobody knows what a Horn Work is and nobody knows how massive this fortification was,” said Doug Bostick, director S.C. Battlefield Preservation Trust, who hopes to make the site a featured stop on a statewide Liberty Trail, working with the American Battlefield Trust.

“This was the literal gates the city,” he added.

As the fort was torn down, a few pieces were kept by nearby landowners to be used as garden walls. Less than 100 years later, the slab apparently was all that remained visible, photographed by a Union soldier at the close of the Civil War, fenced off by artillery pieces with a stack of cannonballs alongside.

Sketches of the Horn Work have been preserved, but they disagree on details. A few archaeological survey trenches were done in the 1990s as part of a reclamation of the square after the wreckage of Hurricane Hugo. That survey found pieces.

This week, students working under design center historic preservation director Jon Marcoux are picking out more from radar images that Marcoux described as little more than blobs anywhere from a few inches to 3 feet under ground.

The hope is a full preservation of what’s left — a footprint for historic interpretations of the site and a guide on what to avoid in any future development of the square.

For Marcoux it’s more than historic preservation. It’s a real world, hands-on project for students that shows the importance of what they do for history.

“Find the footprint so it can be laid out, mapped in and avoided. It gives them a sense of accountability, that we have a responsibility to be stewards of this,” he said.

As an experience it gets, in the words of design center graduate student Rachel Wilson, “a 10 out of 10 cool factor.”

–postandcourier.com