Let’s do a mental exercise about Confederate monuments in public spaces: I’ll describe one that doesn’t exist, and you tell me whether you’d find it offensive if it did.

It sits near a major city, on a scenic patch of federally owned land, in what used to be a Confederate state. It was placed in 1914 by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), a group of elite Southern white women who were highly influential back then and whose main purpose was to push Lost Cause myths about the origins and legacy of the Civil War. Two favorites were that slavery wasn’t the war’s main cause and that human bondage wasn’t all that bad anyway—in fact, it was a largely benevolent institution that rarely involved cruelty. Another was that the Ku Klux Klan, a terrorist organization that arose to restore white supremacy during Reconstruction, was good.

The finished product, sculpted by a Confederate veteran and unveiled with the blessing of President Woodrow Wilson—a Virginia native who wrote a popular history of the United States that described slavery in terms similar to the UDC—features a goddess-like female symbolizing the South, standing on a huge pedestal decorated with shields representing the Confederate states, along with life-sized figures that show mythological beings mingling with Southern soldiers and civilians. In one spot, an enslaved female is holding the child of a white officer. In another, an enslaved man is dutifully following his master off to war.

Sounds bad. And as you may have guessed, I’ve been playing a trick: the monument exists. Known as the Confederate Memorial, it stands in Arlington National Cemetery, and it rises over the graves of several hundred Confederate soldiers, some of whom were brought in for reburial during an era when Northern politicians, including presidents, were keen on public demonstrations of North-South reconciliation. Celebrating this idea mainly involved white people—Black people and their views of the conflict weren’t part of the process—and the mood among Southerners was notably defiant. Speaking at the monument’s unveiling on June 4, 1914, Bennett H. Young, commander-in-chief of the United Confederate Veterans, insisted that the South’s cause was just in every way.

“The sword said the South was wrong, but the sword is not necessarily guided by conscience and reason,” he said. “The power of numbers and the longest guns cannot destroy principle nor obliterate truth. Right lives forever.”

Why is the Confederate Memorial still there in an era when the Black Lives Matter movement has led to widespread statue-toppling? If it were standing in the middle of Richmond, Atlanta, or New Orleans, it might still be up—pending the outcome of a political or courtroom battle to take it down—but it would be so disfigured by graffiti that it would look like a 1970s New York subway car.

The monument is being reviewed by the Army, as reported last summer in the Washington Post, and it’s currently inaccessible to close public viewing. Many would like to see it go away, including descendants of the sculptor, Moses Jacob Ezekiel. But you can probably count on it getting strong support from President Trump, who has vigorously defended military installations named after Confederate generals like Braxton Bragg, Henry L. Benning, and John Bell Hood, a view opposed by Army General Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Trump is also a big fan of Robert E. Lee and thinks statues of him should be left alone. During a rally in Minnesota on September 18, he said Lee was a “great general,” called statue removal the work of “thugs,” and said Lee would have won the Civil War, “except for Gettysburg.”

Whatever happens in the short term, this issue isn’t going away, and the debate is spreading. Last July Fourth, prompted by false rumors on social media, self-styled patriots showed up at Gettysburg, armed and ready to do battle over what they thought was an antifa plan to kill Trump supporters and deface or destroy the numerous Confederate monuments that stand on the battlefield.

“Among them was a guy named Nathan who made the nearly seven-hour drive to Gettysburg from Cuyahoga County in Ohio with three of his buddies,” said a report in the Evening Sun of Hanover, Pennsylvania. “‘It’s history,’ he said. ‘We learn from it so it doesn’t happen again.’

“As he spoke, he said it was no different than people having to learn the history of Nazi Germany. When it was mentioned that there are no monuments to Hitler or other Nazis in Germany, he said, ‘The United States is a different culture. It’s different here.’”

Earlier, the paper ran a letter to the editor by a woman who thinks the Confederate monuments should come down. “‘You can’t erase history!’ they cry, but disgraced General Lee was never 40 feet high, nor did angels herald the Confederate troops as depicted by mythologizing monuments to the Confederacy,” she wrote. “It’s as if the opposition has willingly been gaslit by proponents of the false Lost Cause narrative.”

This focus on battlefields is still fairly new: the Confederate monuments we usually hear about are the ones on public property in cities and towns. The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), a civil rights group based in Montgomery, Alabama, tracks such monuments in a regularly updated report called Whose Heritage?: Public Symbols of the Confederacy. The most recent tally, from September 15, 2020, says that 93 symbols have been removed, relocated, or renamed since the killing of George Floyd on May 25, 2020. Nearly 1,800 monuments, parks, schools, state holidays, and other such symbols remain.

The fate of these displays tends to be decided case by case, with action spiking after a white supremacist crime like Dylann Roof’s 2015 killing spree inside a church in Charleston, South Carolina, or the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. The most recent catalyst was Floyd’s death. During the nationwide protests that followed, several changes happened quickly, including a redesign of the Mississippi state flag, which had incorporated the Confederate battle flag in one corner since 1894. In Richmond, home to monuments honoring prominent Confederates, including Lee, Stonewall Jackson, J.E.B. Stuart, and Jefferson Davis, long-festering opposition to their presence quickly gained ground. Only the Lee statue is still up—pending the outcome of litigation—but BLM protestors have painted it and turned it into a place for celebration and activism.

When I looked at the SPLC’s master list, I was surprised to see that the Confederate Memorial and the Gettysburg monuments aren’t on it. Why? “The SPLC tracks symbols that celebrate the Confederacy on public land,” SPLC chief of staff Lecia Brooks said in an emailed response. “It does not track symbols located in graveyards, battlefields, on private property, or those erected in the spirit of reconciliation.”

This distinction confused me, since Arlington National Cemetery and the Gettysburg battlefield are both government property. (Arlington is managed by the Army; Gettysburg is managed by the National Park Service, which oversees a wide range of battlefields and other sites that are central to American history.) A couple of times in the past, I’ve informally polled this question on social media and found that because both places are considered hallowed ground, the monuments there are sometimes viewed as having special status that’s distinct from, say, a statue of a Confederate soldier in the middle of a town square. This sentiment also shows up in comments attached to articles about the situation at Arlington and in opinion columns.

“Do NOT defile Arlington Cemetery!” one commentor wrote. “Those monuments and gravestones have been there for decades, some more than a century. The time has long past [sic] for people to get their panties in a twist over them.” Writing about monument controversies in the New York Times, Elliot Ackerman, a novelist and Marine Corps veteran, said battlefields are an “area of our complex past that should be left untouched.”

But that’s not logical. The UDC put the Arlington statue there for the same reasons that motivated it elsewhere: pushing Lost Cause propaganda. Do cemetery and battlefield monuments really belong in a separate, protected category? Sometimes they don’t, and we need to decide what to do about it.

I started thinking about these questions because I was a Civil War buff in my youth, and I developed an attachment to battlefields as both historic sites and outdoor settings. It’s easy to forget about the second part, but if you’ve been to any, you know they’re often beautiful—vast greenspaces that have been spared from too much development, are carefully tended, and are educational and interesting. If you get out of your car and walk, you may be in for a strenuous hike, because they’re usually big. For example, Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, located in northwest Georgia and southeastern Tennessee, covers roughly 9,000 acres. The sprawling Vail Ski Resort is 5,317.

I’ve been to a bunch, partly as an outgrowth of a story I did for Entertainment Weekly after the 1990 debut of the Ken Burns series The Civil War. Thanks to Burns, the war and its main talking head, the late author and historian Shelby Foote, briefly became a cultural fad. EW sent me on a road trip to compile a guide for people who suddenly might want to visit a battlefield. Because of that and other travels, I’ve visited many of the best-known sites, including Vicksburg, Shiloh, Chickamauga and Chattanooga, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania, Petersburg, Manassas, Antietam, Appomattox, and my favorite, Gettysburg, where I’ve been twice.

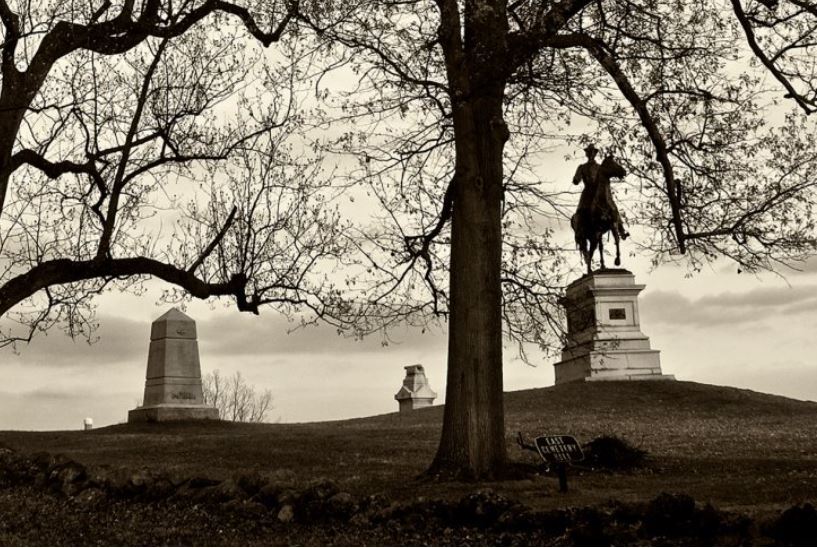

The Gettysburg battlefield is an unforgettable place: 6,000 acres of fields, woods, and ridges next to a small town. It was the setting for a tide-changing three-day battle, the bloodiest of the war, resulting in 51,000 dead, wounded, and missing. Even if you’ve never been there, some of the site names may be lodged in your mind anyway: Cemetery Ridge, Seminary Ridge, Little Round Top, the Devil’s Den. Union troops withstood repeated attacks, including a day-three assault on Cemetery Ridge called Pickett’s Charge, which was turned back at a spot that became known as the high-water mark of the Confederacy.

The initial monument that went up, an urn honoring the First Minnesota Infantry—which held the Union line at Cemetery Ridge on day two—was placed in 1867. New monuments were added regularly over the decades—some grandiose, like the Pennsylvania State Memorial, put up in 1910, and some that are smaller but still majestic, like the Irish Brigade Monument, a Celtic cross guarded at the base by an Irish wolfhound. Many exist simply to tell you that a specific outfit was there: “The 43rd North Carolina Infantry Monument,” “Custer’s Brigade Tablet,” “24th Michigan Infantry Monument, ‘Iron Brigade.’”

According to the Park Service, there are now 1,328 monuments, memorials, plaques, and tablets, and most commemorate the Union. The Confederate statues that draw fire are the so-called state monuments, and there’s one for each of the 11 Confederate states. The first, the Virginia Monument, was dedicated in June 1917—the same month American troops started arriving in Europe to fight in World War I—in a ceremony that celebrated North-South reconciliation and the heroism of Robert E. Lee, who sits on top of the structure astride his horse, Traveller. At the ceremony, Virginia Governor Henry Carter Stuart said, “The imperishable bronze shall outlive our own and other generations…and until the eternal morning of the final reunion of quick and dead, the life of Robert Edward Lee shall be a message to thrill and uplift the heart of all mankind.”

The UDC put the Arlington statue there for the same reasons that motivated it elsewhere: pushing Lost Cause propaganda. Do cemetery and battlefield monuments really belong in a separate, protected category?

The monument’s debut represented a major shift in attitude. According to the Gettysburg Compiler—a digital publication run by students and staff at Gettysburg College—the unveiling was “a crucial moment in reconciliationist memory of the war. For the majority of the previous 50 years, Union veterans and Northern politicians vehemently opposed nearly every attempt to commemorate the Confederacy at Gettysburg.” That changed, explains writer Zachary Wesley, as Union veterans died off and wartime patriotism fueled reconciliationist spirit.

Even so, says Wesley, there were limits: “One suggested inscription containing the phrase ‘They Fought for the Faith of Their Fathers’ was rejected outright” by the federal authorities who oversaw battlefield monuments. “They wanted a politically neutral message in the monuments on the landscape.”

These days, a giant statue of Robert E. Lee can’t be viewed as politically neutral. He was a slave owner who led an army that fought to defend and expand the institution. But as the years passed and more Confederate state monuments went up, the South slowly began to get its way with messaging.

The North Carolina Monument, dedicated in 1929 and created by Mount Rushmore sculptor Gutzon Borglum—a supporter of the 1920s Ku Klux Klan who also worked on the massive Confederate carving at Stone Mountain, Georgia—shows four soldiers advancing toward their fate, which was probably grim. North Carolina suffered the largest number of casualties of any Confederate state—6,000—and the inscription understandably focuses on valor. “To the eternal glory of the North Carolina soldiers,” it says. “Who on this battlefield displayed heroism unsurpassed, sacrificing all in support of their cause.”

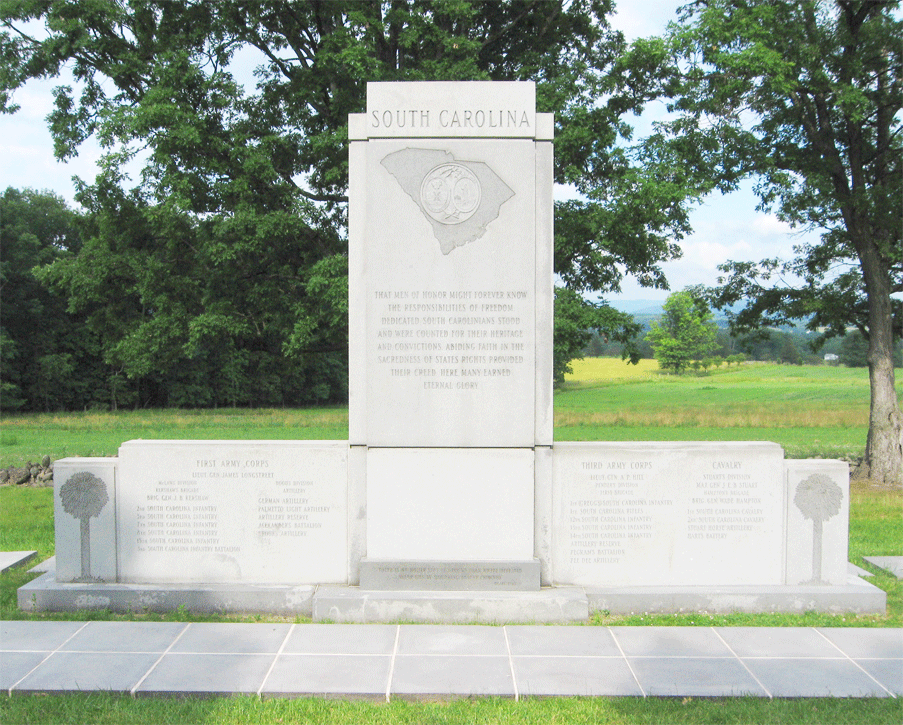

By the time South Carolina was heard from, in 1963, Lost Cause editorializing had shown up in a way that once would have been blocked. “Dedicated South Carolinians stood and were counted for their heritage and convictions,” the monument’s inscription says. “Abiding faith in the sacredness of States Rights provided their creed.” The chief motivation—protecting slavery—isn’t mentioned.

Five more state monuments appeared between 1964 and 1982, including the two that interest me most: Louisiana (dedicated in 1971) and Mississippi (1973). They stand out because they were both done by a talented sculptor who was widely known back then: Donald De Lue, a native of Massachusetts who had trained in Boston, Paris, and New York. I wondered why a Northern artist was involved and whether there was any significance to the fact that these monuments were commissioned during the height of the civil rights era. My hunch was that they were pushed by Lost Cause believers.

That turned out to be right, though one detail surprised me. There had been at least two feelers about creating a Mississippi monument, sent directly by Mississippians in the early and mid-1960s. But according to the Gettysburg Times, the idea also got a significant boost from a Civil War buff named Donald MacPhail, who was chairman of the monuments committee for a group called the Gettysburg Civil War Round Table. In February 1966, he sent letters and photographs to newspapers in both Louisiana and Mississippi, urging officials to consider commissioning a monument. An editorial writer for the Baton Rouge Morning Advocate talked glowingly about the correspondence, in which MacPhail said Round Table members “sincerely believe that all the men from all the states, both North and South…should be honored and represented on the battlefield.”

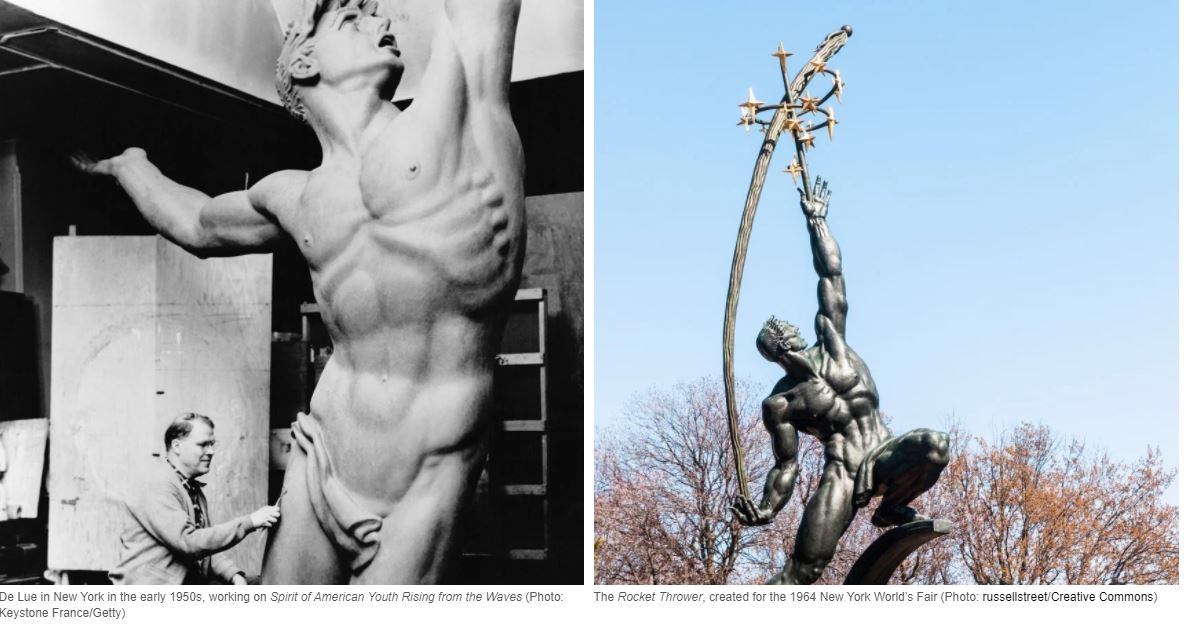

Many influential people agreed, and each state ended up hiring De Lue, who was best known for sculpting Spirit of American Youth Rising from the Waves, completed in 1953 as part of the American Cemetery in Normandy, and the Rocket Thrower, created for the 1964 New York World’s Fair.

Born in 1897, De Lue was a precocious talent. At age 12, he apprenticed with Richard Recchia, a Boston-based sculptor and carver. After a second period of apprenticeship, he went to Paris as a merchant sailor and continued to learn his craft. He was back in New York by 1922 and eventually established himself as an independent artist, in 1934 producing what his biographer, D. Roger Howlett, calls one of his most highly regarded pieces, Icarus.

Describing De Lue’s mature style, Howlett cites influences that include Michelangelo, Rodin, and the muscular statues of classical Greece. His heroic figures are often looking up, in some way engaged with the heavens. Howlett notes that De Lue was impressed with Socrates’ comments in the Phaedrus about the symbolism of the wing, calling it “the corporeal element which is most akin to the divine.” You feel this when you look at the Rocket Thrower, which features a powerful, athletic gesture toward the sky, symbolizing one of themes of the World’s Fair: man’s exploration of space.

Not everyone was wowed. John Canaday, an influential art critic for the New York Times, found De Lue’s work insufferable. Writing about the Rocket Thrower in 1964, he called it “the most lamentable monster, making Walt Disney look like Leonardo da Vinci…a bronze muscle man rising 45 ridiculous feet into the air.”

That’s too harsh: the Rocket Thrower possessed old-fashioned grandeur that was well-suited to its placement and theme. Likewise, De Lue’s interest in godlike figures and higher spiritual planes made him a good choice to design memorials honoring the sacrifices of combat. By the time he got the Louisiana assignment, he’d already done one: a monument to the soldiers and sailors of the Confederacy, commissioned by the UDC and the Sons of Confederate Veterans and dedicated in 1965.

How did De Lue know people from the UDC? According to Howlett, a Miss Désirée L. Franklin, a member of the group who lived in New York, visited him in his studio and asked him to submit a design as part of the Civil War’s centennial. The finished work shows a charging flag bearer modeled on a Texan named Walter Washington Williams, who at his death in 1959 was thought to be the last surviving Confederate soldier. The names of all 11 Confederate states and three border states that supplied troops to the South are inscribed on the base.

This image is conventional; the Louisiana monument is more ambitious and unusual. Known as Peace and Memory, it depicts an angelic figure rising over the body of a young Louisiana cannoneer who’s draped under a Confederate flag. The spirit, holding a trumpet and a flaming cannonball, rests on a laurel, a traditional symbol of heroes. In a 1968 letter to Gettysburg superintendent George F. Emery, De Lue described what he was trying to say.

“A great symbolic female figure representing the spiritual idea of Peace and Memory flies over the battlefield,” he wrote, “blowing a long shrill clarion call…over the long-forgotten shallow graves of the Confederate dead. It is Taps for all the Heroic Dead at Gettysburg.”

n a new book that comes out on September 29, Connor Towne O’Neill, a native of Pennsylvania who now teaches at Auburn, goes on a quest to try to understand the enduring attachment some people feel to Confederate monuments, specifically those that celebrate the South’s most controversial general: Nathan Bedford Forrest. The book is called Down Along with That Devil’s Bones—the satanic reference stemming from a remark by Union General William Tecumseh Sherman, who once called Forrest “that devil.”

There’s no doubt he was a great cavalry officer. “Confederate colleagues dubbed him the ‘Wizard of the Saddle,’” O’Neill writes. “Shelby Foote named him one of ‘two absolute geniuses to emerge from the war.’” (The other was Lincoln.) Fighting in major battles like Shiloh and Chickamauga and in many smaller guerrilla-style actions, Forrest seemed to be everywhere: over the course of the war, he saw combat in Tennessee, Kentucky, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia, and legend has it that he killed 30 men and had 29 horses shot out from under him. In the Ken Burns documentary, Foote seems downright smitten, calling Forrest “the most man in the world” and giddily recalling a time when a descendant let him play with Forrest’s saber.

Forrest is controversial because he was a slave trader who, post–Civil War, served as the first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. In addition, he’s been accused of a war crime: in 1864, at Fort Pillow in western Tennessee, troops under his command massacred surrendering Union soldiers, including more than 100 who were Black. As O’Neill explains, there’s endless debate about whether Forrest was directly responsible for what occurred, but he didn’t seem to feel any remorse. “The river was dyed with blood of the slaughtered for 200 yards,” he wrote in a battle report. “It is hoped that these facts will demonstrate to the Northern people that negro soldiers cannot cope with Southerners.”

O’Neill, who finds Forrest fascinating but morally indefensible, argues that for many modern Southerners, Forrest, more so than Lee, is the South’s most captivating figure. “He’s a folk hero, both Everyman and Übermensch,” he writes, noting that some people believe he could have won if he’d gone head to head against Lee’s conqueror, Ulysses S. Grant. O’Neill calls him “the great hope of the Monday morning Rebel quarterback who refuses to accept the war’s end or outcome.”

Forrest is remembered all over the South. O’Neill says there are 31 monuments to him in Tennessee alone—including a bust in the Tennessee State Capitol that’s been the object of an endless political and legal argument—and O’Neill does deep dives at four places that have seen bitter disputes about Forrest’s legacy: Selma, Alabama, and three cities in Tennessee (Murfreesboro, Nashville, and Memphis).

What interested me most was whether O’Neill would find any pro-Forrest people who present convincing arguments about why statues of him should remain up. He says he didn’t, but he does engage with several passionate, strong-willed supporters. In Memphis, the site of a long-running, ultimately successful fight to remove a huge statue of Forrest that had stood in a public park since 1905, he talks to Lee Millar, spokesman for a local chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Millar reveres Forrest and delights in countering any criticism.

“They say he was a slave owner,” he tells O’Neill. “Well, big deal, so were 11 of the first 13 presidents.” O’Neill points out that he was also a slave trader. “It was tolerated,” Millar says. “You can’t blame him for that because he was just in business.”

O’Neill also speaks with Elizabeth Coker, an activist from Murfreesboro who was on the winning side in a fight to keep Forrest’s name on a building at Middle Tennessee State University (MTSU). To her, people who want to change the name are trying to erase something valuable from the town’s history and the university’s traditions. “It was all so personal,” O’Neill writes. “To protest Forrest…was a protest against their home and history. In other words, a protest against them.” To Coker, younger generations skipped learning about the nuances of history and “just moved on to social justice.”

Nobody likes having their ancestors canceled, and I’ll always respect the right of people to honor the memory of forebears who served in or died in the Civil War. But I don’t think public displays have to be part of the process, and as I read O’Neill’s book, I was swayed by example after example of Forrest’s legacy causing serious pain. Sarah Calise, an archivist at MTSU who was on the losing side of the ROTC fight, talks about the dejection she experienced when the Tennessee Historical Commission, in early 2018, ruled that Forrest’s name could stay up. “Him being a military strategist,” she says, “means more…than the fact that for 50 years, students have been offended and scared to walk by a building—that’s what I can’t come to terms with. Why does your love for this dude outweigh your respect for another human being?”

During the Memphis dispute, O’Neill interviews an Episcopal reverend, Dorothy Wells, who speaks eloquently about the debt owed by those of us who have benefited from slavery and systemic racism. “We have to recognize the injury and care about those who have been harmed,” O’Neill writes, summarizing Wells, “[T]hen we have to see the systems that produce and perpetuate those injuries. And to do that, we need to use our sense of the past to hone our awareness of the present.”

Her words about empathy are crucial. I said earlier that I’m an old Civil War buff; all I meant was that I’ve probably read more about it than the average person, including, among other books, James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, Bruce Catton’s three-volume Centennial History of the Civil War, and the first volume of Foote’s three-volume opus, The Civil War: A Narrative. (Sorry, Mr. Foote. It’s beautifully written, but I realized I’d heard enough battlefield stories.)

I’ve read much more about what happened to Black people in the South after the war ended and the North got weary of overseeing Reconstruction, leaving formerly enslaved people at the mercy of white Southerners for nearly a century. I immersed myself in the subject while researching this book, and it was a searing experience. In particular, I’ll never forget the week I spent scrolling through the Tuskegee Institute news clipping file on lynching, a massive collection of stories about extrajudicial, race-driven murder. Thinking about this legacy of carnage leaves no doubt in my mind that when we’re deciding what to do about any Confederate monuments, we have to respect the feelings of those who are most harmed and threatened by their existence.

Officials at Gettysburg know that eyes are turning toward the Confederate monuments, and that some people want them removed. In 2017, shortly after the Unite the Right rally, a Pennsylvania academic and novelist, Bill Broun, wrote that while Confederate monuments may have once played a role in bringing the two opposing sides of the Civil War back together, “these hunks of marble and granite always possessed another side, too. They valorize and sanitize the horrors of slavery and racism. They also enshrine the notion of the Lost Cause, the debunked fable that the South fought a noble struggle of self-determination. It didn’t. The South fought to defend its sinful addiction to slave labor.”

In a July 2020 story in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Scott Hancock, a professor of history and Africana studies at Gettysburg College, said of the monuments: “The Confederacy in the cultural and spiritual sense actually won the Battle of Gettysburg. They have been successful in rewriting the history of the Civil War, that it wasn’t about slavery.”

The federal government initially dug in. In late June, the Park Service released a statement saying it would not alter or move any monuments inside the park, even when “they are deemed inaccurate or incompatible with prevailing present-day values.”

Things changed in August, when the Park Service announced that it would add contextual panels to each of the 11 Confederate state monuments and to the soldiers and sailors monument. A spokesman said discussions about providing such information started after the killing of George Floyd, and that the aim is to give visitors sufficient background to make sense of what they’re seeing. Another goal is to continue the park’s mission of explaining the Civil War more broadly, as it does in the Gettysburg Museum and Visitor Center. As for timing: a Park Service spokesman told me the panels will begin to be placed “in the coming months.”

I asked Hancock if the panels are enough. He said they’re a start, but he hopes for changes that directly reflect the Black experience in America. “I’d love to see creative and eye-catching monuments about African-Americans, free and slave, that disrupt the narrative of the Confederate state monuments,” he says. “I emphasize state monuments—for me, the Confederate brigade and regimental markers, while not without their own issues, are not the main problem. The reality is that signs, while an important first step, can’t compete with the majesty and size of many of those state monuments.”

I’ll add three things. Arlington, which has an excellent explainer on its website about the Confederate Memorial, should also put up a contextual panel, though I think the monument eventually will be removed. For the contextualizing process to be fair, it should happen all over the country—including New York City, which has several statues that seem iffy and could use a marker or memorial about one of the Civil War’s most grisly episodes, the Draft Riots of 1863. And Gettysburg’s new panels should provide unvarnished details about the history of each monument.

For example, with South Carolina’s monument—which was dedicated on July 2, 1963—it would be helpful to know that one of the dedication speakers was George Wallace, then the arch-segregationist governor of Alabama, who extolled states rights with such fervor that a local reporter wrote, “For a brief moment it seemed as though the Civil War might start over all again.” With the Mississippi monument, there’s more to discuss, because its backers got into a testy disagreement with Park Service historians about what the monument really meant.

The project finally got underway in the late 1960s, and De Lue was hired by a governor-appointed commission to do the job. His Mississippi statue shows a fighting man and a fallen comrade during combat on July 2, 1863, at a famous site called the Peach Orchard. They were part of Barksdale’s Mississippi brigade, led by General William Barksdale, who was killed in action.

When the monument was being planned, Park Service officials were satisfied with De Lue’s visual concept, though the historian—Thomas J. Harrison again—pointed out that it was inaccurate to show the main figure, who’s swinging a rifle, with a bedroll tied around his chest. (Harrison said soldiers didn’t wear bedrolls while fighting; De Lue thought it looked good and kept it.) The problem was the proposed inscription, written by the Mississippi contingent. Labeled “Mississippi July 1st, 2nd, and 3rd 1863,” it began: “On this ground our brave sires fought for their righteous cause; Here, in glory, sleep those who gave to it their lives.”

These days, a giant statue of Robert E. Lee can’t be viewed as politically neutral. He was a slave owner who led an army that fought to defend and expand the institution.

In October 1970, Harrison sent superintendent Emery a memo about Mississippi’s proposal, spelling out changes he wanted to see. He touched mainly on matters of authenticity—like the bedroll and the precise way a Confederate battle flag draped over the fallen soldier should be attached to its staff. He said “Here” should be cut, since no Mississippi Confederates were buried on the field. And at the end of his list, he took aim at the wording on the base.

“The inscription approved by the Mississippi Gettysburg Memorial Commission should be revised to eliminate the word ‘righteous’ in the first sentence,” he wrote, “or else we will have to revise American History.”

This drew fire from Ed C. Sturdivant, a member of the memorial commission and a Jackson, Mississippi–based official in the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Sturdivant was upset that anyone would suggest cutting a word that conveyed the righteousness of the Southern effort. “The words ‘rebellion’ and ‘treason’ have been hurled by emotionally-charged writers and speakers for over 100 years,” he wrote, “but it remains factual that no court of competent jurisdiction has ever made a decision to validate such charges.”

This was another Lost Cause theme: the idea that Confederates were not traitors at all. They were the real patriots, the argument went, because their fight was justified by the Constitution’s states’ rights protections, as spelled out in the Tenth Amendment.

The Mississippians got their way. In late 1971, under a new park superintendent, “righteous cause” was approved. It’s on the monument to this day.

Why did they prevail? It’s not clear from the documents, but I think it’s fair to wonder if political pressure was applied—Senator James O. Eastland, a staunch segregationist from Mississippi, spoke at the dedication. There’s also a public figure in the background whose involvement is a red flag: Tom P. Brady, an associate justice of the Mississippi Supreme Court. Brady was a still-active white supremacist who had written a notorious book in the 1950s called Black Monday, a reaction to the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education. In the book and subsequent speeches, he compared Black people to caterpillar-eating chimpanzees, said Black children were genetically unsuited to be in the same schools as whites, and maintained that Blacks should mark the 17th-century arrival of the first slave ship in North America as a “Thanksgiving Day.”

“And they should set that day aside with some fitting memorial,” Brady said, “because there was conferred upon that segment of the black race the greatest favor that one human being could confer upon another. He was brought from abject ignorance, primitive savagery, and placed in a country that was Christian and civilized.”

When Sturdivant heard from Emery, he showed the letter to Brady, who responded to both of them in a letter that said the South’s cause was indeed a noble one and the monument ought to say so. Defeat in the Civil War “did not make the cause less righteous to those who fought and died for it,” he wrote. “The South has had the most to forgive in this matter and the South has forgiven. Let us hope that the North has done likewise.”

The South had the most to forgive? It’s hard to know what that means, but it probably refers to the ravages of the war on cities like Atlanta, or perhaps to the post–Civil War era of what Southerners called radical reconstruction, a relatively brief period when Black people in former Confederate states were allowed to vote and hold office.

This backstory is relevant. I believe De Lue was sincere when he said his aim was to mark the loss of fallen soldiers on both sides. But the wording on the Mississippi base politicizes it, and the message is offensive, especially given Brady’s involvement with what unfolded. “Righteous” ought to come off.

Alex Heard is the editorial director of Outside and the author of The Eyes of Willie McGee and Apocalypse Pretty Soon: Travels in End-Time America.

–outsideonline.com