It began like many other Fourth of July celebrations Charleston held in the decades after the United States won its independence.

At 3 a.m., the traditional sound of cannon fire erupted from Citadel Green (what today is Marion Square). Members of voluntary militias donned their uniforms and paraded through the streets. The ’76 Association held its annual banquet in Hibernian Hall.

The 33-star garrison flag that flew above Fort Sumter in 1860 was the last to fly over Charleston before it seceded from the Union. A replica hangs above the original at the Fort Sumter Visitor Education Center.

But July 4, 1860, was not just another Independence Day. It would be the last one celebrated before South Carolina decided to secede from the Union, before its troops fired upon Fort Sumter to start the Civil War, and before it sent away so many men to battle other men from Northern states that also celebrated the Fourth.

For those in the city that summer, the deepening divisions would have been easily visible beyond the usual pomp, said Charleston historian Nic Butler.

“There are events in Charleston in 1860 celebrating the Fourth of July and celebrating the Union,” he said. “They specifically mention the Union and the need to perpetuate the Union, but the rhetoric was more like ‘Our country is going down a path that we believe is wrong.’ They’re trying to rationalize their own concept of what is right and just within the concept of the American union and celebrating that on the Fourth of July.”

Many were torn between loyalty to a nation South Carolina did so much to create — from its crucial role in the Revolutionary War to its statesmen who helped draft its constitution — and their deep misgivings about the country’s direction as far as slavery and states’ rights.

“It was a time of a great deal of conflict between Charleston and the larger country,” Butler said. “It was also a time of great conflict within Charleston, within individuals thinking of where their loyalties would lie if push came to shove, which it eventually did.”

A ‘modern police state’

By 1860, Charleston already had started to slip from its heyday before and after the Revolutionary War when the city was the nation’s fourth largest and, by some measures, its wealthiest. By 1859, its population of 40,522 had dropped by more than 5 percent during the previous decade; 21 U.S. cities were larger.

After John Brown’s notorious raid at the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Va., a new vigilance association had been formed to keep tabs on slaves, free blacks and “traitorous” whites, according to Walter Fraser’s history, “Charleston! Charleston!”

“The most populous of the South Atlantic ports and the major distribution center for the state, Charleston more closely resembled a modern police state than any other city in the nation,” Fraser wrote.

It also was a strikingly unequal city: 155 whites — about 3 percent of all white heads of household — owned about half the city’s wealth. Fraser’s history noted most whites in the city didn’t own any land or a slave, and the city’s 3,200 free blacks also included a few very rich while others were very poor.

But Charleston’s influence was still significant, enough so that the nation’s Democrats agreed to hold their 1860 national convention here to try to reconcile the party’s widening rift between its Northern and Southern factions.

It was far from a resounding success.

A ‘Fourth’ in late April

What made Charleston’s Fourth of July celebration in 1860 so different was that many in the city already had celebrated a few months early.

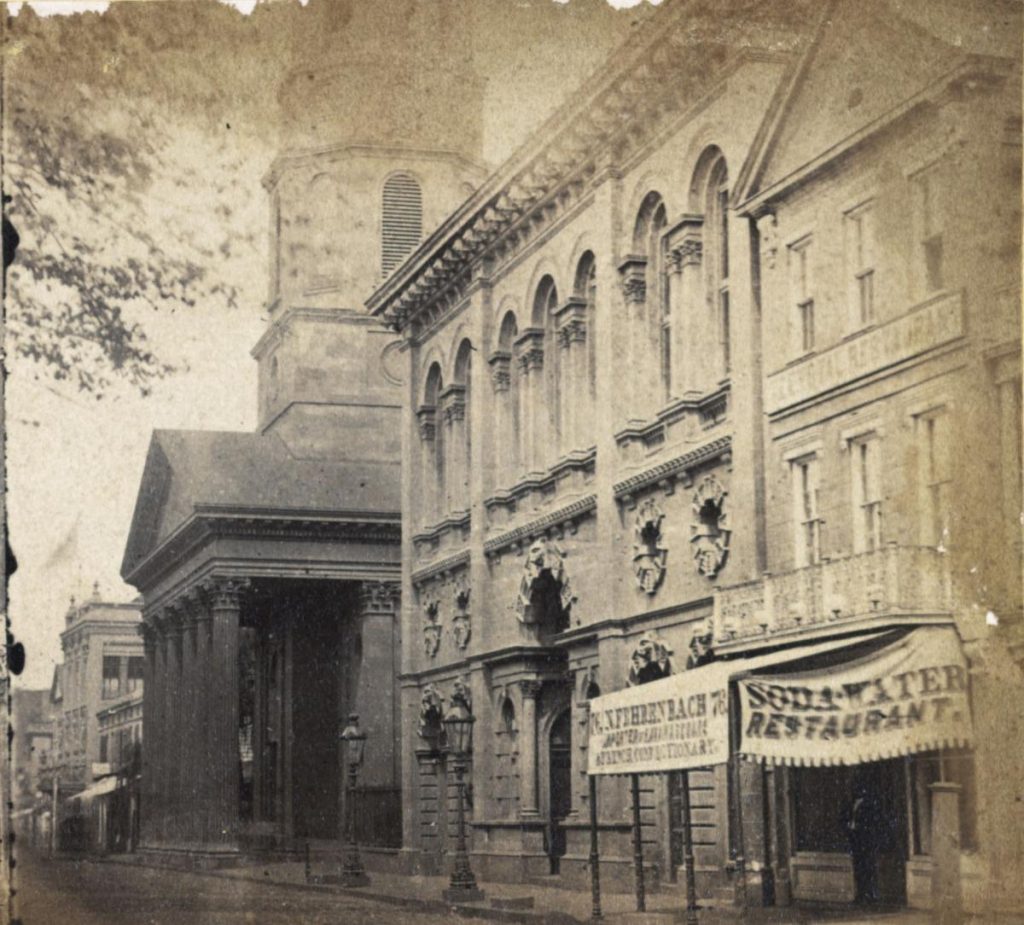

At the end of April, the Democratic National Convention began meeting at S.C. Institute Hall on Meeting Street, a building lost in the city’s epic fire the following year.

The Democratic National Convention began meeting at S.C. Institute Hall on Meeting Street in April 1860. S.C. Institute Hall, often called Secession Hall, is flanked on the left by the Circular Congregational Church and on the right by Nicholas Fehrenbach’s Teetotal Restaurant. This part of the city was destroyed in an 1861 fire. Library of Congress/Provided

While delegates had met inside, other partisans had been gathering on the city streets in and around the hall. They made impassioned speeches, argued a lot and heard pleas against spitting on the heads of convention delegates.

In the end, delegates from many Southern states walked out of the convention, marking the dissolution of the last political party trying to appeal to voters in North and South and searching for some way forward to save the Union short of war.

Secession-minded Southerners celebrated, with The Mercury newspaper declaring the convention’s rupture “will probably be the most important which have taken place since the Revolution of 1776.”

Historian and author Paul Starobin recounted the events in his recent history on Charleston on the eve of the Civil War, “Madness Rules the Hour: Charleston, 1860 and the Mania for War.” The book’s “July 4″ chapter doesn’t refer to the Fourth of July but to the secessionist-led public celebration that erupted across the city after the convention blew up.

His book noted an Ohio newspaper reporter expressing, “Down many a manly cheek did I see flow tears of heartfelt sorry, but on the streets, the tears were of joy.”

“There was a Fourth of July feeling in Charleston last night, a jubilee,” wrote Murat Halsted in The Cincinnati Commercial Tribune. “There was no mistaking public sentiment of the city. It was overwhelmingly and enthusiastically in favor of the seceders. In all her history Charleston had never enjoyed herself so hugely.”

The actual Fourth of July

Many secessionists definitely identified with the revolutionaries of 1776, noted Charleston historian Robert Rosen. “George Washington in his uniform is on the seal of the Confederacy and numerous Confederates (and I imagine declarations of secession) claimed they were doing what the revolutionary forefathers did — seek independence from a tyrannical government.”

“They’re convinced they’re going down the right path; they have righteousness on their side,” Butler added. “Then there were others who saw the handwriting on the wall that something bad was going to happen.”

Former Charleston Mayor William Porcher Miles, then a congressman, gave the address to the ’76 Association in Hibernian Hall, shortly after a poem was read aloud that despaired of what would happen if America split.

Miles did not criticize the poem that night, according to Starobin, but in a speech five nights later, he said, “I am sick at heart of the endless talk and bluster of the South. If we are in earnest, let us act. … It is for you to decide — you, the descendants of the men of ’76.”

And they eventually did.

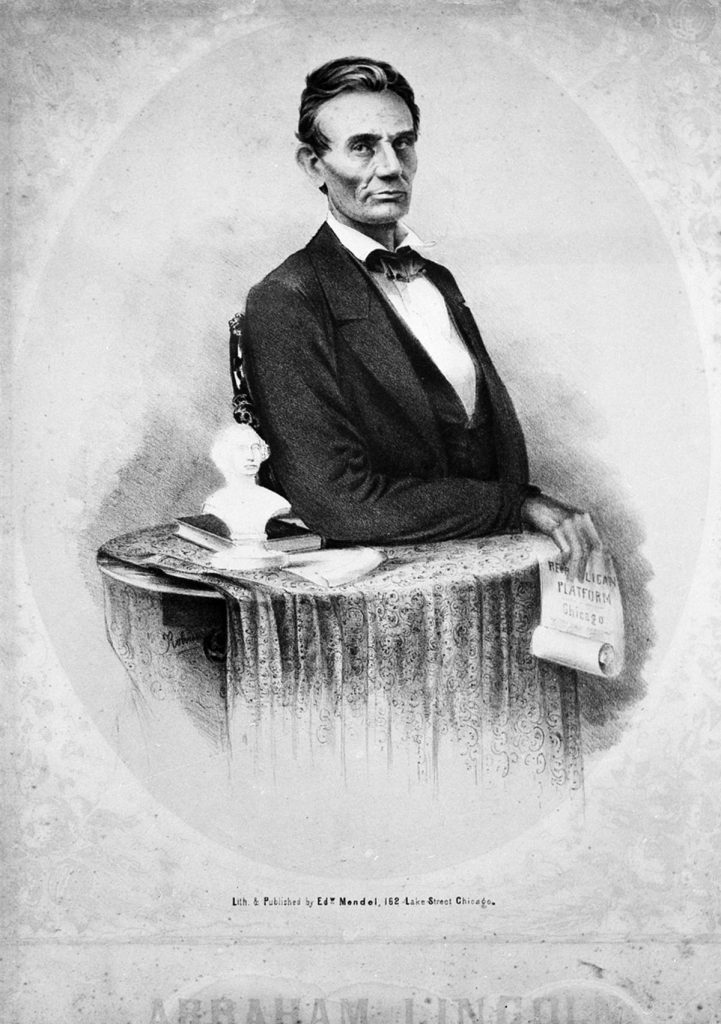

In December, once Republican Abraham Lincoln had been elected president, South Carolina seceded and the first shots were to be fired the next year.

The debate over Charleston’s, South Carolina’s and the South’s future in the Union was no longer a rhetorical exercise but a military one. But that didn’t stop the second thoughts and “what ifs” about the future.

Between the Fourth of July-like celebration in Charleston in late April and the real Fourth of July, Starobin’s history noted that Berkeley County planter and botanist Henry William Ravenel made an entry in his diary.

“Our people do not reflect enough upon these things for themselves,” Ravenel wrote, “but are led on by politicians and made to think that safety, honor, self respect and our very existing depend upon these issues.”