While Juneteenth started as a celebration of the announcement of emancipation in Galveston, Texas in 1865, other accounts of freedom announcements to enslaved communities also offer joyful moments during the Civil War years. In his published narrative Seven Months a Prison, John Vestal Hadley of the 7th Indiana Infantry Regiment recounted such a moment.

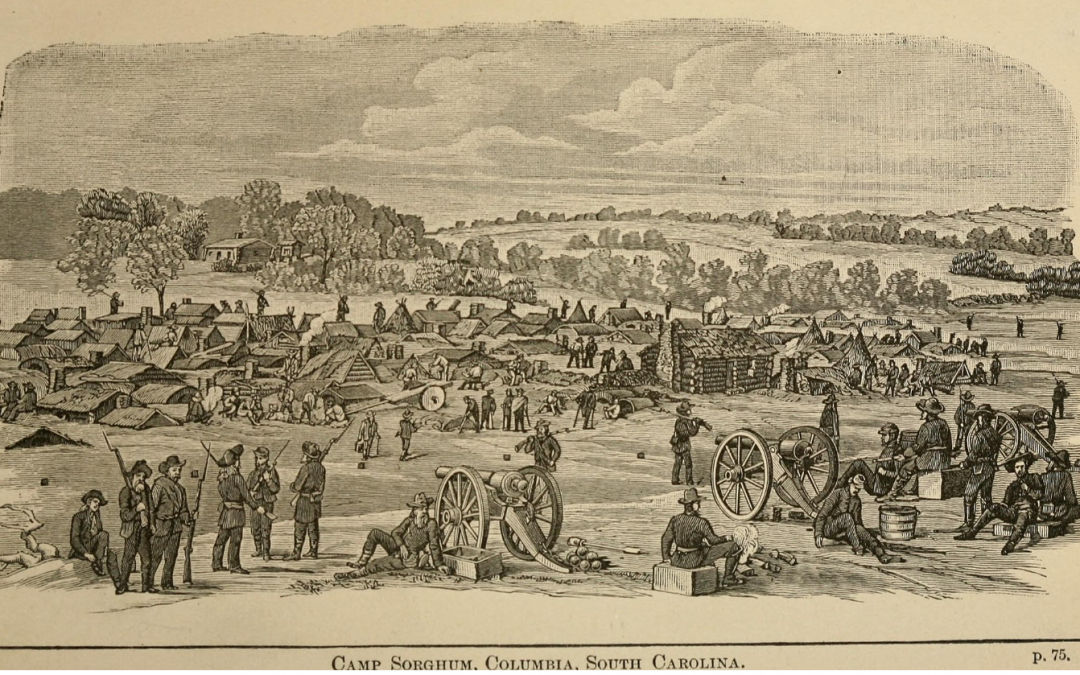

Lieutenant Hadley and his good friend Lieutenant Chisman and two other officers made their escape from Camp Sorghum near Columbia, South in November 1864 and headed into the swamps. Nearly every night, they made contact with enslaved communities to ask for direction and food. Every night, the enslaved people who assisted them gave them clear directions to another cabin or communities a day’s walk ahead and the names of those who could be trusted to help them. With great interest and generosity, the enslaved communities hurried to gather food and see the real live Yankees, setting up a network of protection to shield them from the prying eyes of white Southerners during their night’s stay.

Each time, the enslaved people eagerly asked if Lincoln had given them freedom, and when told “yes,” responded with joy and expressions that they had heard and believed it was true, no matter what their white enslavers had said. The outlandish stories about Yankee cruelty surprised Hadley. He sincerely and calmly explained that no freedmen were forced to freeze to death in the North, were sold by northerners to Cuba sugar plantations, were tied up and used as human fortifications on battlefields, or were shot as human ammunition out of cannons! Meanwhile, Lieutenant Chisman painted a vivid portrait of freedom in his announcements.

Hadley recorded Chisman’s speech about emancipation and freedom in his memoirs. In parenthesis, he also noted some of the listeners’ reactions:

“There is not one of you a slave now, if you only knew it. Mr. Lincoln has declared by that proclamation that the colored people are free everywhere, and he has called soldiers enough into the army to stretch around the State of South Carolina, and compel your masters to let you go. (Tittering.) Thousands and thousands of your race are already free. As soon as they get to the northern soldiers they tell them to go free, to do what they please, to go where they please, to work when they please, and for whom they please. And they go to work and earn lots of money, five dollars a day, some of them; and they get it themselves every cent of it; and they buy fine clothes, and great big high hats; and the women have fine satin dresses and parasols; they have fine horses and buggies, and drive headlong through town, splashing the mud on everybody. (Snickering.) Then, when Mr. Lincoln finds an old colored person who can’t labor, he gives him a house, feeds him, and cares for him. Why, there is a place close to Washington, where Mr. Lincoln has built houses for, and is feeding and caring for fifteen hundred old and crippled colored people. Then, too, we have rebels in the North, who don’t want you to get free; and when Mr. Lincoln finds one of these men, he takes his land from him, and his horses, and everything he’s got and gives them to the slaves who run away from their masters….

And it’s all a lie about you having to go into the Federal army. The rebels tell you this to scare you. You don’t go in unless you want to. They won’t let the girls go in at all, but have them go back in the country and work in houses altogether, sewing and making clothes for the boys in the army; and they get paid for it, too.

All the colored boys that want to go into the army to fight their old masters, Mr. Lincoln’s hires them to go; and he gives them all the nicest clothes, every one just alike; he gives each one a pair of new shoes, and pair of blue pants, a fine blue cloth coat with brass buttons all up before, and great big brass things on the shoulders, and a new black hat with a brass eagle on each side and a yellow cord around it, with tassels hanging down behind; and the prettiest new guns — why, they are as bright as a new dollar, and have great long spears on the end to stick the rebels with. They are not a bit like the old rusty things you see the rebels have. And they are the proudest fellows you ever saw when they get their new clothes on, and their guns and white gloves, and stretched out into line. Then it would do you good to see them fight in battle. They just won’t be whipped. They just raise the yell, and go at the rebels, and never stop shooting and sticking them until they run them every one. And they sometimes capture their masters. Once, in the army, a colored boy caught his master, and had him for a prisoner. The master thought that because the boy had once been his slave, he would not mind, and refused to go when the boy told him to. This made the boy mad, and he snatched up his gun and was going to shoot the old fellow, but he begged so that he didn’t, but made his old master go back to his tent and black his shoes (tittering) and chop wood enough to get his dinner with. (Renewed tittering.) He then left him with the other prisoners. And they make officers out of the colored men, who have nothing in the world to do but stand around and tell the other soldiers what to do. Why, they say they have got one over in Tennessee who rides a horse and commands fully ten acres of men.” (I think the last remark was suggested by a story told of General Logan.)

“If I were one of you I would never work another day in the fields, under your master’s lash, but I would leave here before sun rise, and take every colored man and woman with me I could….”

While Hadley enjoyed explaining emancipation and freedom, he worried that Chisman’s exaggerations painted a false picture of freedom. He confronted his comrade about it. Chisman replied, “This is no time for your moral lectures, old granny; I’ll hear none of them till we get home.” And then explained that he could do the most good for the Union cause and help ensure that the enslaved people would find freedom for themselves if he did paint a rosy picture.

Despite the many unfortunate falsehoods in Chisman’s version of emancipation, freedom, equality, and opportunity, it is still a unique scene that Hadley left in his memoir. And the stories and the confirmation that the promise of emancipation was true left a “hope of relief” from bondage every night as the escaped prisoners journeyed through the deep South. Although the recorded reactions of the enslaved communities is limited in Hadley’s writing, the joy of the moment with the confirmation of promised freedom should not be overlooked.

–emergingcivilwar.com