For decades, Donald Trump has been known as a narcissistic, bombastic New York businessman who craves the media spotlight. However, if you unpack the dynamics of his support as a politician, Trump’s stunningly successful run to the top of the Republican ticket is less New York chutzpah and more Southern demagogue. Trump’s appeal to disaffected whites, especially working-class white men, evokes the racial politics of the white South.

For a century and a half, a possible alliance between lower-income black and white Southern voters has been blocked by elites appealing to racial division. There is plenty of racism in the North, of course, though the South is the epicenter of this brand of right-wing populism. As the economic fortunes of working- and middle-class white men have faltered in the past generation, resurgent racism has filled the political vacuum. While anti-immigrant politics have their own history in America going back to the anti-Catholic Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s, Southern right-wing populism has often been anti-foreign as well as anti-black. Trump has been able to fuse the appeals of nativism and racism in his appeal to aggrieved whites.

For decades, old-style white supremacy has been increasingly virulent at the level of Southern state and local politics, but until Trump it did not have a plausible national leader. Blueblood Republican presidential nominees like Mitt Romney and the Bushes, or mainstream standard-bearers like John McCain and Robert Dole, were the antithesis of right-wing populism. This year’s Trump revolt is the instrument of long-simmering resentment against both parties.

The Democrats, meanwhile, have become the party of cosmopolitan cultural liberalism—friendly to a mosaic of immigrant groups and to newly asserted rights demanded by the gay, lesbian, and now transgender community, as well as to redoubled demands to complete the movement for equal rights for blacks and women. All of this created the preconditions for a Trump, whose criticism of P.C. politics blends anti-black, anti-foreign, anti-rational, and anti-modern sentiments. The America that his base wants to make great again is a white America—the America of the pre–civil rights South.

AFTER THE ADVANCES OF the era of Martin Luther King Jr. and Lyndon Johnson, the 1970s ushered in a generation of Southern Democratic governors like Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton, who presided over biracial governing coalitions of racial liberals and economic moderates. As recently as 1992, Democrat Ray Mabus in Mississippi—Mississippi!—was that sort of governor. Mabus received about 40 percent of the white vote in the 1987 election.

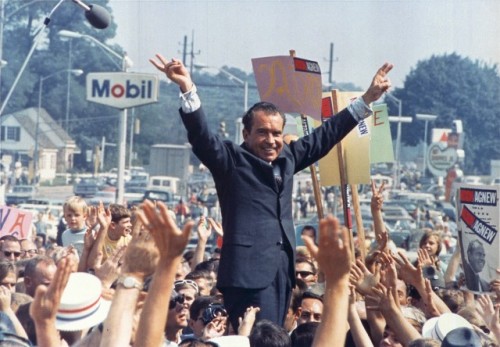

Since the 1980s, the Republican Party has doubled down on the Southern Strategy advanced by Richard Nixon—running against civil rights and black gains. Here, Nixon gives his trademark “victory” sign while in campaigning in Philadelphia in 1968.

But those days are over. A lot of the jobs turned out to be low-wage jobs. Traditional industries that paid decently, like textiles and furniture, all but collapsed. The New South economy was confined to small high-tech oases. The Republican Party doubled down on the Southern Strategy advanced by Richard Nixon—running against civil rights and black gains. An influx of immigrants only added to the backlash.

By the beginning of this decade, most Southern whites had moved decisively to the Republican Party, most of the Southern Democratic Party had become a black party, and the biracial governing coalitions were unattainable. “White Democrats in the South are gone,” says Hodding Carter III, the journalist who was a spokesman for President Carter and whose father was a crusading Mississippi publisher and one of the South’s great liberals in the civil-rights era. With the advent of the Tea Party, which anticipated Trump, the dog whistle became almost audible. With Trump, the racism has become explicit. But it never really went away.

At its core, today’s reactionary right is a marriage of the ideological children of the Southern slave aristocracy and the right-wing edge of the business elite—within a single political party. In the Civil War era, Northern business interests and the anti-slavery movement were united in the fledgling Republican Party; today’s Republican Party is the opposite—it combines resurgent racism and far-right business hostility to government.

In the Old South, racism was the key to preventing an alliance of poor whites and poor blacks that would threaten both white supremacy and the continued power of the planter aristocracy. This was especially true after the Populist revolt of the 1890s when, for a brief period, poor whites and poor blacks united in a common cause against the upper crust. The response by the Southern oligarchy was twofold. First, the white elite disenfranchised nearly all blacks and a good portion of the white working class with a variety of political and economic devices, including the infamous poll tax and changes in the system of land tenure that caused white smallholders as well as blacks to become sharecroppers. Second, the planters and their urban business partners developed and perfected a brand of politics based on turning poor whites against blacks to head off the biracial coalition of working-class blacks and whites that could again threaten the power of the bourbon elite. By 1910, virtually all black elected officials were expunged from the states of the former Confederacy, along with nearly all black voters.

More than a century after the destruction of the original Reconstruction, Trump and the GOP have returned to the same dual strategy of voter suppression and the politics of racial resentment to block liberal advances or a biracial coalition. The epitome of affront to the America of white supremacy was the election of the nation’s first black president, Barack Obama. “By 2010, there was full horror that a black man was now president and a full-fledged liberal,” says Hodding Carter, who served as assistant secretary of state for public affairs under President Carter and is now a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC). “Obama was at the door and soon in the bedroom. It brought back all the atavistic, Old South fears.” Before Trump began bashing immigrants, he promoted the canard that Obama was born in Kenya, a lie that sent exactly the right signals to the base.

IF YOU WANT TO SEE a 20th-century politician who prefigured the Trump coalition, look no further than Alabama Governor George C. Wallace. A four-time presidential candidate and former Democrat, Wallace helped deliver the White House to Richard Nixon in 1968 when he headed the American Independent ticket and garnered 13.5 percent of the vote and carried five states with 46 ballots in the Electoral College.

George Wallace, running as a third-party candidate in 1968, stunned observers by gaining white working-class support in the North. Here, Wallace announces his candidacy for president in 1968.

Wallace stunned political observers by showing surprising strength in the North. His support among blue-collar workers cost Democrat Hubert Humphrey dearly in such states as Ohio, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Illinois, where Wallace votes exceeded Nixon’s margin over Humphrey. A mid-September AFL-CIO poll showed roughly one in three union members supporting Wallace, and a Chicago Sun-Times poll showed that Wallace had the support of 44 percent of white steelworkers in Chicago.

“Trump’s voters are the sons and daughters, mostly the sons, of the Wallace voters,” says Ferrel Guillory, director of the Program on Public Life at UNC Chapel Hill. Every modern Republican presidential candidate starts with a white base in the South. What is new is Trump’s audacious attempt to take the white politics of the South national via an aggressive demonization of immigrants, Muslims, women, blacks, and minorities of all stripes.

Wallace, interestingly, began as a racial moderate and a protégé of Alabama Governor “Big Jim” Folsom, who disliked racial politics and ended every speech by stepping into the crowd to shake the hand of the first black supporter he found. Following the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, an intense backlash of white opinion in the South called for massive resistance. Attacked for being soft on the race issue, Wallace lost his first race for governor in 1958. Afterward, Wallace told his inner circle, “no other son-of-a-bitch will ever out-nigger me again.”

As the civil-rights movement burgeoned, Wallace repositioned himself to lead the white resistance and famously declared, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” Wallace, a political innovator of the first rank, pioneered the sublimation of racial rage into hatred of government, not just the federal imposition of black rights in a second Reconstruction, but government meddling generally. This anticipated the politics of Newt Gingrich, Paul Ryan, Ted Cruz, and the Tea Party because it connected Southern racial resentment to the anti-government libertarian economics of the business right. The explicit racism became latent and coded—a dog whistle. The stars of today’s Republican right are all practitioners of this art. But Trump went them one better.

“Trump doesn’t tweet dog whistles, he blasts foghorns,” wrote Washington Post op-ed columnist Eugene Robinson. In this, Trump echoes an earlier band of 20th-century Southern demagogues. Southern politicians such as Mississippi’s Theodore Bilbo, South Carolina’s “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman, and Georgia’s Eugene Talmadge were more blatant and direct than Wallace in demeaning blacks. And like Trump, they relished the fact that they were not about issues—for issues (other than race) mattered little in traditional Southern politics. Instead, they concentrated on providing a venomous, racist form of entertainment for the white working class—another parallel with Trump.

In the Old South, the central role of race crowded out discussion of other issues and other possible coalitions. Said one Southern judge, “Issues? Why, son, they don’t have a damn thing to do with it [getting elected].” In Politics in the New South, a leading text on Southern politics, University of Florida political scientist Richard K. Scher explains:

“Since it was possible, indeed legitimate and necessary, to blame blacks for the ills of the South, the politician need not then bother with serious discussion of public problems. Issues were of little or no significance, since the causes of southern problems were not a colonial economy and maldistribution of resources leading to poor education, ignorance, poverty, and disease. Rather, they were the consequence of a large black population that sucked energy and resources from whites in the region.”

Using the government to improve public welfare might increase health and well-being for the South’s impoverished population—both black and white. But this was unacceptable because it “might lead to increased levels of equality between the races.”

James K. Vardaman, elected governor of Mississippi in 1903, explained, “Why squander money on [black] education when the only effect is to spoil a good field hand and make an insolent cook?” Real issues had the potential of arousing the public, causing people to pay attention, ask questions, and demand that their leaders solve problems.

The disdain of issues is also pure Trump. It doesn’t seem to matter that Trump is all over the place on serious public questions. One week he is anti-banker; the next week is he saying reassuring things about all the bankers he works with. He likes Planned Parenthood, then he doesn’t. But just as “issues” didn’t matter to whites who clearly got the message from Talmadge, Bilbo, et al. that they were defending the white race against blacks, the Trump constituency gets the deeper message. It’s not about issues as conventionally understood. But it’s very much about the white working class sense of unresolved grievance and the scapegoating of blacks and immigrants. Like the older demagogues, Trump is all ethos (“trust me”) and pathos (“fear them”), no logos or argument.

AS RECENTLY AS THE TURN of the current century, scholars were celebrating the success of the Second Reconstruction, which emerged from the coalition of Democratic presidents (Truman, Kennedy, and Johnson) working with civil-rights leaders and activists. In his seminal history The Two Reconstructions, written in 2004, Swarthmore political scientist Richard Valelly argued it was a triumph across both the courts and parties (specifically the Democratic Party) that allowed the Second Reconstruction to become institutionalized and durable. Whereas the First Reconstruction was destroyed in 1876 by a cynical alliance between a resurgent Southern planter class and Northern Democrats, it seemed as if the modern civil-rights movement, changing racial attitudes, and the alliance between rights activists and the national government had moved the nation into a period where the New South was quite different from the Old South and the United States as a whole had turned the page. The culmination of America’s new maturity on race was the election of Barack Obama.

Now it is clear that the celebration was premature. In the post-Reagan era, the GOP has become a traditional white Southern party, even more so than in the Nixon era. Republicans have shifted from a party of small government to a party that is fiercely anti-government. The 1970s-to-1990s governing coalition of blacks, racially liberal whites, and moderate business leaders that elected governors such as Carter and Clinton has been overtaken by a Republican governing coalition of neo-segregationists, anti-government libertarians, and right-wing business leaders. The rightward tilt of the Republican Party in the South, in turn, has strongly influenced the national GOP as the Tea Party base destroys moderates from Maine to Arizona with primary challenges or threats.

Today in the states of the Old Confederacy, the white Republican Party has a stranglehold on governorships, state legislatures, and nearly all congressional seats outside black-majority districts (into which African American voters have been packed in order to weaken their voting strength elsewhere.) “There are very few biracial coalitions left at the state level,” says Representative David Price of North Carolina, one of the few remaining Southern white Democrats in Congress. The same racial pattern has made deep inroads into border states such as West Virginia and Kentucky. States like Tennessee that once elected economically populist, racially moderate Democrats are now deep red.

As Republicans more flagrantly became the white party, Democratic statewide candidates, be they white or black, have failed to “attract sufficient white votes to marry to the united support provided by African American voters,” write political scientists Charles Bullock and Ronald Gaddie. An exception is Virginia, whose northern suburbs are distinctly non-Southern.

After passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, under the direction of New South governors such as Carter in Georgia, Clinton in Arkansas, Mabus in Mississippi, and Mike Easley in North Carolina, a number of Southern states “adopted parallel strategies of bolstering public education, improving physical infrastructure, and aggressively recruiting new economic enterprise,” writes UNC’s Guillory in his 2012 essay “The South in Red and Purple.” As growth brought new revenue, these governors supported higher education, sought public school reforms, sustained Medicaid, and launched various activist government initiatives. But in the 2000s, and especially in the wake of the 2008 economic crash, Republicans countered by “widely challenging even the premises of government,” using radical anti-government rhetoric and actions. The right’s devotion to “privatization, their adherence to budget cutting, and above all, their determined resistance to tax increases,” Guillory writes, was an assault that took the wind out of the sails of New South–style governance in state capitols across the region. And race, once again, became central to the politics of division. Southern white voting was going Republican at the presidential level before it worked its way down to the state and local level. Trump did not cause the resurgence of racial politics, but he intensifies that trend and takes it national.

The parallels between the attacks on voting rights in the First and the Second Reconstructions are striking. Between 1890 and 1910, the black electorate was radically reduced by a combination of “literacy tests, poll taxes, stringent residency requirements, requirements that registration occur months before elections,” writes Valelly, as well as inconvenient hours, harassment, and intimidation.

Mirroring restrictions put in place following the First Reconstruction, the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University has estimated that the changes put in place in just 2011 and 2012 have made it “significantly harder for 5 million citizens to vote.” Here, Senator Patrick Leahy, center, speaks during a news conference on Capitol Hill in Washington, Wednesday, Sept. 16, 2015, in support of a fix in the Voting Rights Act. From left are, Senator Benjamin Cardin, Senate Minority Whip Richard Durbin, Hilary 0. Shelton, director to the NAACP’s Washington Bureau, Leahy, Senator Mark Warner, and NAACP President Cornell William Brooks.

In the midst of the Second Reconstruction, we see a new wave of voter-suppression techniques. Since 2011, the Republicans have moved with strategic intensity to limit the vote of key Democratic constituents—primarily the elderly, minorities, and the young, abetted by a partisan Supreme Court. The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University has estimated that the changes put in place in just 2011 and 2012 have made it “significantly harder for 5 million citizens to vote.”

The multidimensional GOP onslaught picked up speed in 2011, when 19 states passed 25 laws to make it harder for people to vote. As Heritage Foundation President Jim DeMint recently admitted, it was a coordinated strategy to suppress voter turnout among groups that favor Democrats. In a radio interview, the former South Carolina senator said, “It’s something we’re working on all over the country, because in the states where they do have voter-ID laws you’ve seen, actually, elections begin to change towards more conservative candidates.”

It may be counterintuitive to imagine Trump, a New York billionaire and reality television star, as heir to the politics of Bilbo and Wallace. But this is the coalition he leads and this is his message. Forty years ago, there was broad hope that the New South was becoming more like the rest of America. Trump’s appeal suggests that working-class America is becoming uncomfortably like the Old South. Can Trump be stopped?

THERE IS A SOUTHERN SAYING that Reverend William Barber II likes to recount: “A dying mule kicks the hardest.” Barber, who is president of the North Carolina NAACP and founder of the Moral Mondays movement, says the white reactionaries know they will ultimately lose. The challenge is more than about voting rights, says Barber. It is the “intersection of voting rights and worker rights.”

Barber believes that the path forward is for liberals to stress a moral narrative that explains to working-class whites how a great many government programs help a great many more whites, like themselves and their neighbors, than they do minorities. Barber cites a Harvard Medical School study saying the decision by 25 red-state governors to opt out of the Medicaid expansion offered by the Affordable Care Act has resulted in the deaths of thousands of working-class and poor whites. Barber’s message: The attack on people of color and immigrants by the right is, “in fact, hurting all of us.”

Increasingly, there are liberal islands in a sea of red, as Southern cities split with states on social issues. The New York Times reports that the “digital commons, economic growth and a rising cohort of millennials” have remade the culture in Southern cities from Birmingham to Dallas to Jackson to Raleigh. Howell Raines, a Southerner and the former editor and editorial page editor of The New York Times, argues that the Southern Republicans are living in “a dream world,” pretending their ultraconservative policies can go on indefinitely.

Raines says the overwhelming white flight to the Republican Party allowed the reactionaries to defeat the biracial Democratic coalitions, but now “we are seeing a new coalition politics, in which Hispanic, black, and Asian voters are joined by Democratic-leaning younger whites who, unlike older white voters, do not care about dog-whistle issues.” Change is afoot as a multiethnic Democratic Party has the opportunity of breaking the Republican lock on the South, starting with Florida, Virginia, and North Carolina, with Georgia and then Texas on track to go purple in the near future. But that future may be a way off.

In North Carolina, where three moderate white Democratic congressmen have lost their seats in the past ten years, Hodding Carter is less sanguine about the Democrats “making a coalition to break the back of one-party racial politics.” Since Jimmy Carter’s presidency, which began with the former Georgia governor winning a series of Southern states including Mississippi, “there have been a few more moments of possibility” for an enduring biracial coalition, but each “lasted like a heartbeat.” Hodding Carter recalls a moment in 1989 when The New York Times ran a photo of three sons of the South—Governors Mabus of Mississippi, Clinton of Arkansas, and Buddy Roemer of Louisiana—ambitious young Democrats with “aggressive agendas, Ivy League pedigrees and boyish good looks,” who personified the New South’s politics.

Each had a program focused on economic development, education investment, and fiscal moderation, which appealed to both whites and blacks in three states that were ranked in the bottom 12 nationally for per capita income. “You kept thinking, this time we will reverse it,” says Hodding Carter. “We are putting down the foundation for a new workable party, but it was built on sand. Yes, we could elect individuals, but after their time in office, it all falls apart.”

For now, white moderates have been stymied in their efforts to build a biracial—or now a multiracial and cosmopolitan—electorate in the South. Yet Democrats may not need the South to spare the country Trump. The electoral math works for the Democrats to win the White House based on the West Coast, the Northeast, and the industrial Midwest while conceding the South to the Republicans.

Their challenge is to prevent Trump from taking a Southern strategy national, as Wallace began to do, for there are plenty of aggrieved, downwardly mobile whites outside the South. However, if Democrats cat get beyond the current spasm of hate and offer something hopeful to an angry white working class, the long-term demographic trends are in their favor. Even so, this is a frightening time for the republic. Rarely have the differences between the two major political parties been so broad, so clear, and so significant, and a presidential election so consequential.