“Deep away in the heart of a city, Charleston, a city called America’s most historic, a city referred to as most conservative in a conservative state, tourists give a cursory look at its Negro boarding places … An excursion through … Charleston will reveal Negro eating places of description conceivable and inconceivable as given below.” — From the introduction to ‘Negro Restaurants in Charleston, South Carolina,’ written by Laura L. Middleton in 1936.

Janvier Orrante is a Nebraska-based jewelry designer who puts gold spider forms on iPhone cases and silver bats on earrings. In the kitchen, her choices are more conventional: She always puts eggs, butter and cheese in her grits.

“I make them after my great-aunt Camille Wray taught me,” Orrante said.

Wray learned the recipe from her father, Juan Gomez, who in the early 1930s ran The Gomez Lunch Room at the corner of South Market and East Bay streets. Grits were Wray’s favorite thing to order at the all-day café, abubble with the catching-up chitchat of farmers who’d brought tomatoes and greens from the islands and vegetable vendors on break.

It might have been the eggs, butter and cheese she liked so much, since most everything else on the menu was stripped down to comport with the budgets of men who played whist at the market when they couldn’t find work. Potatoes boiled in pork skin. Fried cabbage. Peas and rice.

Orrante doesn’t know for sure, because she didn’t realize until The Post and Courier contacted her for this story that her standard breakfast represents the legacy of Black-owned restaurants in downtown Charleston. Until she ran the information past an aunt, she had no inkling that her great-grandfather owned “the most fashionable” café in the City Market.

So, since 1937, the guide has been sitting at the University of South Carolina’s South Caroliniana Library, tucked away with biographies of African American leaders; overviews of charitable organizations and articles on folklore filed by Middleton and nine other Black writers.

The whole collection has received close scholarly attention just once, when Jody Graichen in 2005 wrote her master’s thesis on the archive. (“Since I was studying public history, I literally stumbled upon these records,” she said in a phone interview.)

Yet the forgotten document is a remarkable one, rich in restaurant names and descriptions which never surfaced in city directories, local newspapers or The Green Book. It captures a landscape of everyday eating on the peninsula at a time when mills and wharves mattered more than hotels and highways.

Unfortunately, the picture isn’t entirely clear: Middleton and her colleagues reported to White editors, and almost surely crafted copy with their biases in mind.

Evidently unaware that Middleton was a Black woman born in Adams Run, the author of a 2016 history of New Deal-era foodways classified Middleton’s contributions to the project as “grossly racist,” citing phrases such as “Negroes in South Carolina Lowcountry are well-known good cooks.” Middleton also wrote harshly about gambling, messiness and “clowning most of the day.”

According to her granddaughter, though, Middleton had high standards and strong opinions.

And like the Black-owned restaurants she wrote about, she made certain they weren’t forgotten.

“The Moon Glow’s golden roasted and fried chicken and deliciously flavored barbeque are unsurpassed; and while the races are separate and distinct, white patrons not infrequently roll up in their cars, toot their horns and enjoy curb service here.” (The Moon Glow, 24 Kennedy St.)

Americans today tend to think back fondly on the Federal Writers’ Project as a thoughtful and sensible public service, akin to twice-a-day mail delivery. That was far from the prevailing sentiment during the Depression, when the notion of giving government money to fancy urbanites who couldn’t be bothered to hoist a pickaxe was a talking point for the anti-Communist crowd.

“Of all the Federal Arts Projects created in 1935, the Federal Writers’ Project held the dubious distinction of being considered the ‘ugly duckling of the lot’,” Catherine A. Stewart wrote in her 2016 book, Long Past Slavery: Representing Race in the Federal Writers’ Project.

Stewart added that a supporter of the program in 1938 allowed that the 6,000 former newspaper reporters; journalism school graduates and failed poets on the dole “committed mayhem upon the body grammatic.” And that was the most benign of their missteps: They waved guns at their bosses; showed up for work drunk; popped pills and missed deadlines.

“For example, that write-up of the Charleston Museum, a good piece of work … could have been done in one day,” a South Carolina field supervisor fretted in a letter to the state director. “(It) was allowed to occupy seven weeks of one worker’s time.”

To ward off criticism and recoup the government’s investment in literature, federal director Henry Alsberg had to come up with an inoffensive project that could occupy writers in all 48 states. He conceived The American Guide, a series of regional, state and city guidebooks which would document the country and encourage citizens to tour it, spending as they went.

“We had to insist upon proper representation of the Negro in these books,” Editor of Negro Affairs Sterling Brown later recalled. “For example, Tennessee would send in something about Nashville and not even mention Fisk University.”

Alsberg hired Brown in 1936, hoping he would help bring more Black writers on board to make up for oversights of both the inadvertent and highly intentional kind.

Brown’s appointment rankled White state directors in the South, who didn’t care for the feds questioning their racist conclusions that Black residents were better off enslaved and that concerns about lynchings were overblown.

“I believe Alabamians understand the Alabama Negro and the general Negro situation in Alabama better than a critic whose life has been spent in another section of a country,” Alabama State Director Myrtle Miles sniffed.

While plenty of objectionable characterizations still made it to print, Brown made clear from the start that “emphasis should be placed upon the Negro as an integral part of the city’s pattern of life — he should be shown in relation, rather than a thing apart.”

In other words, even though the Federal Writers’ Project was responsible for collecting oral histories from formerly enslaved people, Brown didn’t want contributors to overlook the vibrancy of contemporary Black life. He urged state directors to gather information about Black businesses and Black institutions.

Those assignments often went to Black writers. But in the segregated South, recruiting Black writers meant finding separate offices for them: The Federal Writers’ Project set up standalone Negro Writers’ Units in Virginia, Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina, the last of which was headquartered at Benedict College in Columbia.

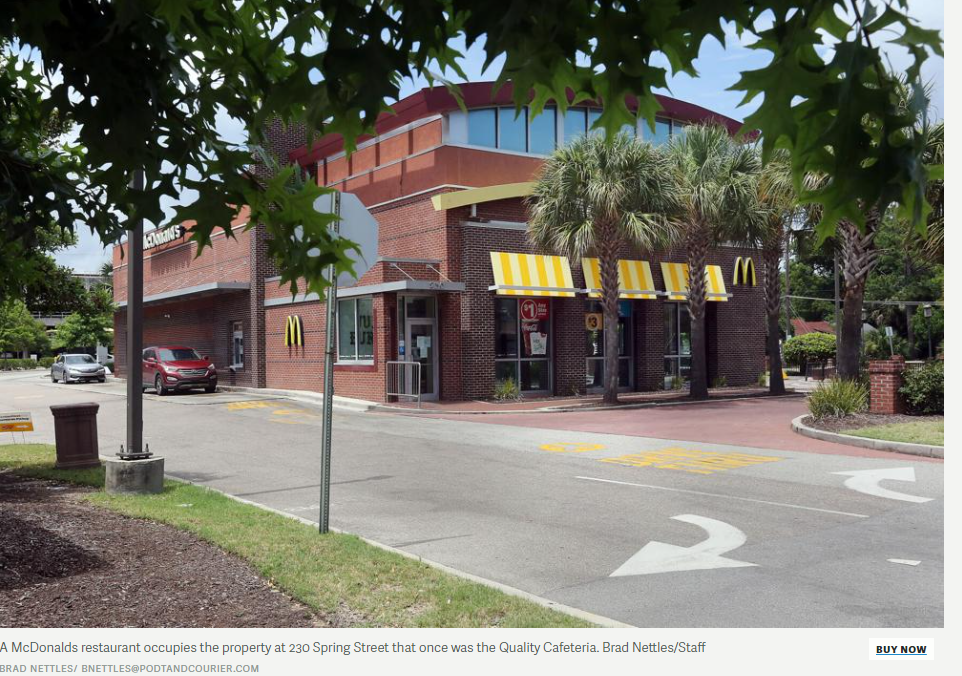

“This cafeteria has a billboard, the heading of which is ‘What to Eat for Enjoyment of Food.’ Below this sign is a list of the common foods, mostly meat and rice, cabbage, bread and coffee. This list is not in keeping with the billboard heading, but the frequenters of the Quality Cafeteria think so.” (Quality Cafeteria, 230 Spring St.)

Having received orders to establish a Negro Writers’ Project, South Carolina state director Mabel Montgomery assured Alsberg that she would start staffing just as soon as she was cleared to hire more people.

“I fear that it will be difficult to secure Negroes on relief who possess suitable qualifications, but I shall make every effort to locate them,” she wrote. “There is no doubt that this race has made valuable contributions to South Carolina in music, folklore, literature, loyalty to the whites, etc. Should all these be united in one harmonious chapter under Negro contributions?”

Although Montgomery didn’t include food in her list, food was a hugely important component of The American Guide.

Each state was tasked with submitting essays for America Eats, an envisioned compendium of culinary traditions: The Mississippi state director suggested the volume should include entries for political barbecues; fish fries “which are surprisingly popular over the State” and dinner on the grounds at singings, as well as dinner on the grounds at all-day preaching.

The Georgia state director made a case for watermelon cuttings and cane grindings. The Tennessee state director nominated New Year’s dinner, “a standard celebration predicated on hog jowl and turnip greens.” The North Carolina state director asked Alsberg to leave room for chitterling struts; commencement basket picnics and tobacco barn Brunswick stew.

South Carolina’s wish list ran as follows:

“St. Cecilia Ball Breakfast; St. Andrews Society Dinner; Hibernian New Year’s Dinner; A Fish Stew on the Pee Dee; Schutzenfest in Charleston; Hunting Clubs; Negro Wake; Barbecue among Po’ Buckra of Horry County; Oyster Roast; Tom and Jerry on Christmas Morning and Congaree Church barbecue.”

Given the go-ahead on oyster roasts, Garland H. Hamlin wrote up an Elks Club event on Folly Beach, sketching a scene of “Large tables, spread out over the sandy strand, strawn with all the assorted accessories for roasted oyster eating: Oysterettes, pickles, olives, catsup, Worcestershire sauce and melted butter … beer flows freely, kegs and kegs of it, beer in bottles, beer in cans, beer of every brew.”

Still, restaurants made almost no extended appearances in Federal Writers’ Project materials, published or otherwise. Apparently, they didn’t quite jibe with the ethnographic bent of the initiative.

By contrast, chronicling successful businesses was well within the scope of the Negro Writers’ Project. Brown was a firm believer in “racial uplift” and hoped to see the Black middle class celebrated in project guides.

In Florida, most of the staff writers were “drawn from the Black bourgeoisie,” according to Stewart, the author of Long Past Slavery.

“They had their own take on the importance of being able to contribute to a national narrative about Black contributions,” she said. “They were interested in talking about stories of Black advancement. Not just the horrors of enslavement, but how African Americans had not just survived, but thrived.”

“The favorite dish served here is pork chops and rice; often fish and rice. The frequenters are patiently awaiting the watermelon season. Then there will be melon-eating contests. One spectator remarked that the fellows appear to live more off the fun and smell of food than off food.” (The Paradise Lunch Room, 127 Line St.)

Montgomery hired Elise Ford Jenkins to supervise the S.C. Negro Writers’ Project. Jenkins was an educator who had studied at Fisk; Hampton Institute; S.C. State University and Benedict; her husband was a leading doctor in Columbia.

Jenkins in turn hired Middleton, Samuel Addison Jr., Lillian Buchanan, Eva Fitchett, Mildred Hare, Augustus Ladson, Hattie Mobley, Robert Nelson and Simmie Smith. The National Archives and Records Administration did not respond to a request for their employment records, but Graichen suspects Jenkins met several of them through the Adult Teachers Summer School held at S.C. State.

It didn’t take long for the writers to realize they would be heavily censored.

“It’s dangerous to talk about racial injustice,” said Ethan Kytle, who with Blain Roberts covered the S.C. Negro Writers’ Project in Denmark Vesey’s Garden: Slavery and Memory in the Cradle of the Confederacy.

Kytle and Roberts wrote about Ladson turning in an interview with Susan Hamilton, who had been enslaved. If an enslaved woman gave birth at 8 a.m., Hamilton told Ladson, she was expected to be back to work by noon.

Nonsense, Montgomery said when she read the account.

She chalked up the report to “bitterness” and sent a White woman to re-interview Hamilton. Not surprisingly, the White woman came back to her office with a radically different report.

Even so, the Black writers were blunt in an essay entitled “Negro Education in South Carolina.” As Graichen put it in her thesis, they “took whites to task for their indifference to inadequate educational standards for blacks in the state.” Education was sacred to the contributors, Middleton included.

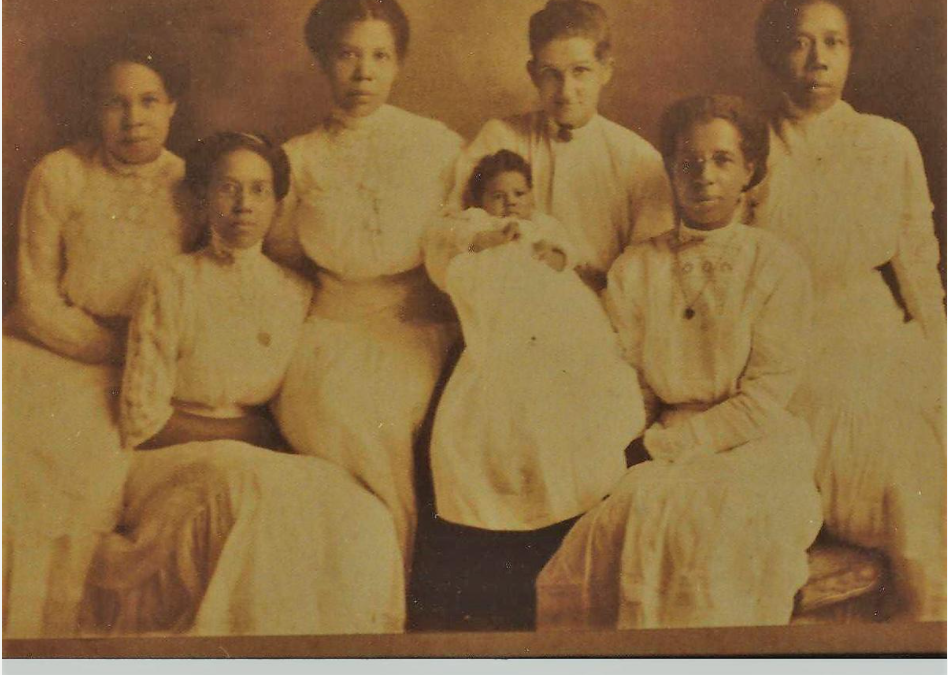

“Her sisters were all seamstresses and lacemakers, and they pooled their resources to send her to normal school,” said Verde Fisher, Middleton’s granddaughter. Fisher last year inherited the role of unofficial family historian when Middleton’s youngest son died.

Census records suggest Middleton’s father, Stephen Deas, was 75 years old when Laura Deas was born in 1892. The shoemaker and blacksmith helped build the little country school that Deas and her four older siblings attended. In the wintertime, they’d walk there with roasted sweet potatoes in their pockets to keep their fingers from freezing.

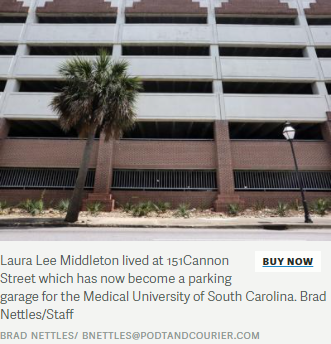

After Deas died, his widow, Julia, moved their family to Charleston. By 1910, they were living at 151 Cannon St. But after graduating from the Avery Institute, Deas left the city every summer to teach English to children on the Sea Islands who grew up speaking Gullah exclusively. During the year, she taught at the Wallingford Academy on Wadmalaw Island, a private school affiliated with the Presbyterian Church.

Deas married Clarence Middleton, a successful brick mason. His work was so acclaimed that when the developer of the Empire State Building in 1930 needed someone to supervise the Black masons laboring to speed the massive skyscraper into existence, Middleton got the job.

For that project, Laura Middleton accompanied her husband to Harlem. More commonly, though, she stayed in their Spring Street house when he relocated for a few months on business: He always brought his wife a new tea set when he came home.

“She had so many tea sets and so many fine pieces of furniture,” said Fisher, who remembers thinking all grandmothers when asked for a snack would present iced tea in a crystal glass and cookies on a silver tray.

Clarence Middleton died of endocarditis on Sept. 26, 1934, at the age of 43.

From that day forward, Laura Middleton only wore gray or white when going out. At home, she wore housedresses dotted with little flowers when dusting her tea sets or making gumbo with shrimp and corn caught and grown by her cousins.

“Her rice was perfection,” Fisher said. “There was a great deal of pride in keeping her home clean and having delicious food. She made these wonderful meals: She had a black fruitcake with figs from her tree and pecans we would sit and crack. I have never in my life since tasted anything that even comes close to it.”

Middleton also raised three children, who Fisher said were terrified of inviting their mother’s disapproval. While Middleton spoke softly, the words she chose to describe a distant relative whose children weren’t well dressed; a neighborhood “rummy” who gravitated to drinking places or a church member who wagered on cards were sharp. They left a mark.

“In the evening before bed, her kids were allowed to go outside, but they followed her like ducklings,” Fisher said. “She was not trusting that everyone in the village was who she wanted to influence her children.”

“In the waterfront section and Negro settlements in downtown Charleston are where the dingy, smoky eating huts do business. … Here it is the custom to ask the customer, ‘Did you get enough to eat?’ rather than ‘Did you like the dinner or was the meal balanced enough for you?’ The most that is served in these places is meat and rice or fish and rice. There must be rice. Without it the meal is incomplete.”

Fisher described her grandmother’s demeanor before she read “Negro Restaurants in Charleston, South Carolina,” which vibrates with a fastidious tone. (“If my grandmother was alive today, she’d be mortified that she misspelled ‘tourist’,” Fisher e-mailed after receiving a copy of the typed manuscript.) Middleton never mentioned her participation in the Negro Writers’ Project to her grandchildren, despite the family’s high regard for written expression.

Her brother-in-law at one point worked for the White House, writing condolence letters to survivors of fallen soldiers. Her son wrote out sermons for a Charlestonian who Fisher characterized as “a well-known minister who knew the Bible by heart but was illiterate.”

Like her peers involved with the project, Middleton turned in several assignments, including an interview of “Uncle” Dave White, who was born into slavery.

Although it’s impossible to establish the editing process that produced her final copy, academics who haven’t looked past Middleton’s language have identified her in their papers as a “Southern white.”

For instance, Middleton wrote that White’s “never changing graceful disposition typifies the true Southern Negro of pre-Civil War days; a race that was commonplace and plentiful at one time, but is now almost extinct, having dwindled in the face of more adequate educational facilities.”

That last part sure sounds like Middleton.

You can hear her, too, in her description of The Paradise Lunch Room, which is where Silas Green From New Orleans performers ate when their circus came to Charleston.

“This is the locality where Negro hilarity and sunshine prevail despite what some would consider serious unemployment,” Middleton wrote. “In some respects, these Negroes show admirable qualities … They will say, ‘We got no job but the Depression never ain’ gwine send us to the crazy house.’”

“Give me some of these names!” said Regina Bradley, associate professor of English and African Diaspora Studies at Kennesaw State University and author of Chronicling Stankonia: The Rise of the Hip-Hop South. Bradley, a scholar of Southern Black culture and respectability politics, reviewed Middleton’s restaurant guide at The Post and Courier’s request.

“If the WPA was supposed to be documenting these experiences, it can’t just be, ‘I talked to these random Negroes.’ If you’re going to be a restaurant critic, be a restaurant critic,” Bradley said, contrasting Middleton’s approach with that of novelist Zora Neale Hurston, who worked for the Federal Writers’ Project in Florida.

“Zora Neale Hurston would have stayed at the City Market; she would have stayed at The Moon Glow,” Bradley said. “Mrs. Middleton was trying to distance herself; trying to show and prove that we are functioning, productive members of society. She had a bit of a challenge here: How do I stay true to my roots but present them in such a way that I don’t hinder the uplift of the race?”

Bradley reads the guide as intended for a White audience but sees subtleties in “the focus on police and patrolling.” For example, Middleton noted conduct at The S&L Lunch Room was “much reserved in that it is near King Street where the law is constantly patrolling.”

Was that aside supposed to assuage White fears of Black spaces? Or warn Black patrons of a potentially dangerous situation?

Either way, Middleton’s guide is the only surviving record of most of the restaurants featured in it.

On Feb. 1, 1939, a man was sentenced to 15 days on the chain gang for breaking a woman’s glasses at The Paradise, but The Charleston Evening Post didn’t include the venue’s name in its report. On Jan. 15, 1937, the owner of The Moon Glow was arrested for buying stolen whiskey, but its name didn’t appear in the paper either.

With the exception of Orrante, who has a familial tie to The Gomez Lunch Room, all efforts to reach descendants of restaurateurs listed in the guide yielded nothing.

For all its flaws, then, Middleton’s guide is an important piece of journalism.

Middleton knew as much almost a century ago.

After the S.C. Negro Writers’ Project was halted permanently on July 8, 1937, leaving only White staffers on the program’s South Carolina payroll, Middleton and Augustus Ladson sent a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

“We know that it is not your will that we are ‘last to be hired and first to be fired,’” they wrote. “But as father of all Americans, you should be consulted where injustices are concerned.”

Weeks later, an administrator responded to explain state and local officials had the final say in which workers were retained or dismissed.

None of the S.C. Negro Writers’ Project contributors were ever brought back to work.

Reach Hanna Raskin at 843-937-5560 and follow her on Twitter @hannaraskin.

–postandcourier.com