Walking to Mitt Romney’s hotel room on election night, down a hallway that wasn’t long enough, I found myself asking the sorts of probing questions that an industry of self-help experts argue are essential to a well-led life: When was the last time I’d really been happy? What was it that I really cared about in life? Those experts may tell you such riddles open a path to happiness, but I had long suspected that they were employed mostly by those who believe—really, really believe—that the love of their life is just waiting on Match.com. I couldn’t remember ever asking myself questions like this on a night when we’d won. I suppose I’d always thought self-examination and introspection were what losers did instead of celebrating.

It had been a long campaign. I had turned 60 on a campaign plane a couple of weeks earlier, an event I’d made sure no one “celebrated.” But it wasn’t really me or my birthday I was thinking about; it was my father’s. In six weeks or so, he would turn 95.

Ninety-five is a pretty unimaginable number, but then turning 60 was a baffling notion as well. In the long hours after concession, waiting for the sun to come up to muddle through the inevitable awful day after, I suddenly realized I had an answer to one of the perennial campaign questions, “What do you plan to do after the race?” This had always been an easy question for me because, win or lose, I knew what I’d do: another campaign. I had never been interested in working in government of any sort and was confident I’d be terrible at the effort, even if it had appeal. I was one of those guys whose usefulness, if any, was in the taking of Baghdad, not the running of it.

But now I had a different sort of answer. I wanted to spend time with my mother and father while it was still possible. And I knew exactly how I wanted to do it.

* * * * *

One of the great virtues of the South is the assumption that football is important. When my father and I decided to attend every game Ole Miss played that year, no one thought it was odd that we were spending months going to football games. In the South, organizing a life around college football games seemed like a perfectly reasonable endeavor.

The love of college football and its importance in life’s scheme are natural for a Southerner but difficult for the uninitiated to grasp. When I first moved to New York City in the 1980s, it was not a happy time in the city’s fortunes. Everyone talked about crime, the way Alaskans talk about bears, or ski patrollers discuss avalanches. But I loved it. Like generations of expats in a foreign land, I fell into a crowd of fellow countrymen: southerners and mostly Mississippians.

Every fall weekend, we would slide into a deep, predictable funk. We wanted to watch football—real football. At some point before each weekend, a depressing series of phone calls would commence among southern expats over the scarcity and quality of the football options on New York City television. “Holy Cross versus Harvard? Can you believe it? My high school played better football.”

It was much as I imagine growing up in a culture with wonderful, distinctive food—India or the Szechuan Province of China—and moving to a drab place where the only options were awful strip-mall restaurants that were all the more insulting for their claims to authenticity: “Real Indian” or “Genuine Chinese.”

They called these sad Northeastern college efforts “football,” but it was hardly a creature of the same species. Once a few of us dragged up to see Columbia play, and we left before the half. It wasn’t just what was happening on the field; it was the entire experience. The few students who condescended to come seemed more interested in the mocking hipness of playing at being football fans. Some actually read books during the game. This was like bringing a six-pack to church to get through the sermon. “Like Communion served to atheists at the Joyce Kilmer rest stop on the New Jersey Turnpike,” a friend described it as we rode back on the subway. Another friend was so depressed he flew home the next weekend for the Ole Miss-LSU game and never came back to New York. I didn’t blame him a bit.

Most of us had come to New York because we believed, on some level, that we had no choice. It was both a test of who we were and a way to define who we might become. It wasn’t a fear of failure at home that drove us to New York, but a fear that success at home might be all too satisfying. The expats in my crowd had no illusions about the South. We were scornful of those we deemed “professional southerners,” those living in New York who tried to define themselves by some pretense that they came from a more genteel and cultured world.

But all of that changed on fall Saturdays, when we would gather in a self-congratulatory orgy of southern boosterism and shared loathing of the Northeast brand of football. It gave us an opportunity to be smug, a joyful rarity for us in New York, but most of all it was an affirmation that though we may come from a not-so-perfect spot, we believed in something larger than ourselves that made us better than ourselves. In a confusing world, this festival of southern football was a constant that rarely disappointed.

By late October, on the Thursday before the next game, we all were eager to get back to Oxford. That was the rhythm of a fan’s life, and I loved that it was now the focus of our lives. We drove to Oxford. It was warm, more like August than November, one of those perfect days that are a reminder of how much summer will be missed. In the distance, a familiar song carried through the soft air. My father perked up, like a bird dog on a scent.

“Band practice,” I explained.

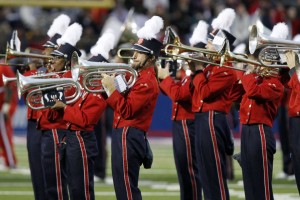

We had walked to the edge of the campus and were in front of the band building. THE PRIDE OF THE SOUTH: OLE MISS BAND, the sign read. It was redbrick and formidable. The Ole Miss band, dressed in shorts and jeans, was practicing for homecoming. The band director conducted from a stepladder. He’d shout instructions to move this section here or that section over there, and a seemingly random group of students would transform into order. It resembled some large-scale game of chess with human pieces. They were practicing the “Ole Miss Alma Mater,” a favorite at the games. It was lyrical and elegiac, a song from my youth. It was an odd song to play at a football game, sad and haunting, but this was Mississippi, and anything that could evoke a sense of loss was powerful medicine. I looked over at my dad, and he was smiling.

We watched as the student musicians joked around, looking bored, like a random collection of students who had been handed these odd things called instruments. But then, when the director’s baton went up and they poised to play, something quite miraculous happened. They were transformed from just kids into some force transcendent. They became magicians conjuring miracles from the air.

In Geronimo Rex, Barry Hannah’s brilliant first book, he described the powerful effect of a southern marching band: “The band was the best music I’d ever heard, bar none. They made you want to pick up a rifle and just get killed somewhere.” So it was with the scruffy bunch who would form up on Saturdays in brilliant uniforms and transform themselves into the “Pride of the South” band. They tore into a medley that was a standard of every game. At the heart of it was the revised version of “Dixie” that the band now played.

Like every Ole Miss fan, I’d grown up with the Ole Miss band playing “Dixie,” an assumed ritual like the singing of the national anthem. It was the Ole Miss football anthem. It was our anthem. Today it is popular for sports fans to call themselves “nation”: “Red Sox Nation” or “Who Dat Nation” for the New Orleans Saints. But when “Dixie” played at Ole Miss games, it represented the lost glory of an actual nation. No one ever died for the right to form Red Sox Nation. Tens of thousands died for the brief existence of the Dixie nation.

In those days, the band would play “Dixie,” Colonel Reb waved his sword, the Confederate flags would fly, and for that moment it could recapture a past as glorious as the last dance at Tara, when victory was assured and soon the Yankees would be taught a lesson. At the finale, the crowd would rise and join as one, shouting, “The South shall rise again!”

Inevitably, the irony, if nothing else, of having a team that was more than half African American charging to battle behind Colonel Reb and the Confederate battle flag became difficult to ignore. The school dropped Colonel Reb in 2003 and banned Confederate flags. That left “Dixie,” which was a tougher call to ban. Though frequently assumed to have been a Confederate anthem, the song was actually a favorite of Abraham Lincoln, who had it played at the announcement of Robert E. Lee’s surrender. But its fate as an Ole Miss regular was probably sealed with the crowd chant of “The South shall rise again” that rose up with the finale. It didn’t help that the Ole Miss band wore uniforms modeled after Confederate battle dress. But the idea of Ole Miss football with no “Dixie,” no Colonel Reb, and no Rebel flags was hard for many to grasp. As one Mississippi friend of mine, a former McGovern worker who now gave large sums to the Democratic Party, put it scornfully, “We might as well be the Syracuse of the South.”

Instead of a complete ban on “Dixie,” a compromise was reached. A modified version of “Dixie” would be allowed as part of a longer medley. Like the approaching death of a loved one, the final days of the original “Dixie”—“From Dixie with Love” was the full title—were marked with solemn ceremonies: the last playing at a special performance at the Grove in 2010. For the true believers, it was like the killing of the Latin Mass for a cheaper, junk-food variety more digestible to a broader audience.

Before my dad and I went to the season’s first game at Vanderbilt, I realized that a part of me would want the games to be as they had always been. I remembered too well that simple joy when the cheerleaders would throw bundles of Confederate flags into the stands to be passed around like muskets at dawn reveille. Had somebody handed me a Confederate flag when the Rebels took the field, I’d have waved it out of pure muscle memory and maybe more. Or if that sweaty hot night in Nashville, Colonel Reb had made one more fateful, doomed charge through the goalpost chased by the band in their old-style Confederate uniforms playing the unrepentant “From Dixie with Love,” I’d have stood and shouted, “The South shall rise again!” at the end with a clean heart. It would have been a piece of frozen time handed to me by a benevolent God, and I’d have licked it like an ice cream cone, joyous and grateful.

But I’d never be that young boy again, and while the tall man in the hat and the sport coat who would pick me up after every touchdown was still here, now he had his hand on my shoulder to keep a little steady. I knew the Rebel flags wouldn’t wave again, and I’d never be swung through the air while rebel yells exploded all around us and the band broke into “Dixie.” But listening to even that ersatz “Dixie” brought those moments back, how it felt jumping up on the wooden bleacher to be a little taller and hug my father and know then, without a doubt, that I was the luckiest kid on earth.

We stood watching the band work through the medley, moving smartly in formation now, as if the music demanded respect. They came to the “Dixie” section, and it wasn’t quite the same as the old “Dixie,” but by God it was awfully good. It was a song of loss, and that made it more real and stirring than an ode to victory. When I had heard the song as a child, I always assumed, probably like every other white-southern son, that it was an ode to the southern way of life, that while we might have lost the battle called the Civil War, we had won that other war, that our values and our way of life had proven superior to the crasser, mercantile ways of the North.

But now I understood it wasn’t about some hidden victory; it was just about loss. We lost. They won. It sounded sad because it was sad. It made you want to cry because loss was sad and defeat painful. The South was part of that brotherhood of cultures which learn to erect such beautiful homages to loss that it was easy to forget that they were still about loss and suffering. Surely this was their purpose. To be who I was when I was a boy who was to be raised in a world that taught you it was right and essential that your people had been defeated but it was also right and essential to respect and mourn the loss. This, perhaps more than anything, defined what it was to be southern: to know the world celebrated your defeat, and to join in that celebration was required to be accepted into the company of civilized men and women. It is still living with the Civil War that separates the South from the North, more than victory or defeat. No one in the North thinks about the Civil War, which is the ultimate humiliation for the South. To win a war is to be free to move on. To be conquered is to live with the consequences forever. The descendants of Joshua Chamberlain are no doubt rightly proud of his actions turning back the charge that desperate day on Little Round Top, but are they haunted by it?

It was here at Ole Miss that the University Greys mustered up so they could meet their fate at Gettysburg, so eager and honored to lead Pickett’s Charge into the slaughterhouse, attacking up the hill in daylight against fixed positions, dying and dying and dying until there were none left to die. It is in their honor the statue stands in the Grove.

The music faded, and the band director barked new instructions. Next to me, my father sighed. “You know, I’m tired,” he said, and he looked it. Now that the rush of the music was passing, we were facing a long walk back.

“Should we call Mother to come get us?” “Nope. Let’s walk. Too nice outside.” It was a beautiful, warm afternoon, one of those days you want to frame and keep to pull out on the gray days to remember. We headed off as the band kicked into “Rebel March,” the classic beats of a fight song. We both smiled. He put his arm around me, and we walked back through the campus.

This article has been excerpted from Stuart Stevens’s book, The Last Season: A Father, a Son, and a Lifetime of College Football.