Visitors come from all over the globe to see Charleston’s beautiful, centuries-old historic buildings. Yet very few people — even locals — ever make the half-hour drive to Awendaw to see what may be the Lowcountry’s oldest, and most mysterious, man-made structure: the Sewee Shell Ring.

A one-mile footpath through the Francis Marion National Forest ends at the ring’s quiet, isolated spot adjacent to the intracoastal waterway. Once there, it’s hard to really “see” what’s right in front of you, though interpretive signage helps. Yet when viewed from the air, the mystery of the Sewee Shell Ring comes to life.

Those who study shell rings generally have more questions than answers. Why and how they were built are debated topics among archaeologists, social scientists and historians.

Archaeologists with the U.S. Forestry Service, stewards of the property, distinguish shell rings from shell middens. Though made of similar materials, a midden is, in its simplest terms, a trash heap of discarded oyster shells and other debris. Downtown Charleston’s White Point Garden, historically known also as Oyster Point, is an example of what was once a shell midden.

A shell ring, however, is not a refuse heap, but a designed structure that was purposely built by one of the earliest homo sapien groups to settle along North America’s southeast coast. Believed to have been built about 4,000 years ago, Sewee’s ring is among the oldest — as old as the great pyramids of Giza or even the final stages of Stonehenge’s construction.

It is one of the few remains of a once vibrant indigenous culture that lived in the Carolina Lowcountry centuries before European settlers arrived.

Unexplainably, shell rings are found only in four disparate places around the world: Japan, Colombia, Peru and the Southeastern United States.

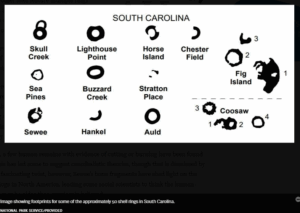

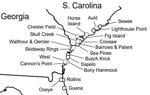

The Sewee ring is the northernmost of about 50 rings identified in North America, though the authors of an article in the Journal of Archaeological Science (August 2021) believe more will be discovered using LiDar, a technology that uses pulsed laser light to create models of what lies under the earth’s surface.

Some rings, like Sewee, are nearly circular, as in the letter O. Others are oval, more like a U. Some stand alone, as does Sewee, while other sites feature multiple rings clustered together. Sometimes they have openings that face the estuary, as does Sewee’s, though others open onto the mainland side of the ring.

The diameter of Sewee’s ring is about 150 feet, smaller than the average of 225 feet. Its walls are believed to have once been 10 feet high, steeper than most.

Despite these differences, shell rings all feature a distinctive wall surrounding an open plaza that was once cleared of debris. The walls are made mostly of oyster shells, with mussels, clams and periwinkles mixed in. They also contain the occasional pottery shard, early tools and bone fragments, leading archaeologists to conclude that their builders hunted, fished and raised families during a time when their culture was transitioning from independent egalitarianism to a social community hierarchy.

Unlike some rings, a few human remains with evidence of cutting or burning have been found in Sewee’s ring. This has led some to suggest cannibalistic theories, though that is dismissed by most experts. In a fascinating twist, however, Sewee’s bone fragments have shed light on the domestication of dogs in North America, leading some social scientists to think the human-canine connection may be older than previously believed.

While archeologists are coming to understand more about the physical nature of shell rings, their purpose remains a mystery. No one has yet established why these structures were built or what purpose they served. Could they have defined a residential area? Did they serve a civic, ceremonial or religious purpose? Perhaps they were some type of recreational field similar to what the Mayans created in the Yucatan? No one knows.

As today, any built structure in the Lowcountry’s hot, humid climate faces challenges. The Sewee Shell Ring has been damaged over the centuries by hurricanes, forest fires, erosion and sea-level rise.

Yet the greatest contributor to its demise was its accidental discovery by transportation workers in the late 1920s, who unfortunately mined nearly half the site for materials with which to pave Highway 17. They had no idea what they were destroying.

Today, a boardwalk that surrounds the ring’s remains offers some of the most tranquil views in the Lowcountry, an idyllic setting with soaring, graceful shorebirds and the clacking of little crab claws from those that make their home in the pluff mud surrounding the ring’s edge. It’s definitely worth the drive to Awendaw.

–postandcourier.com