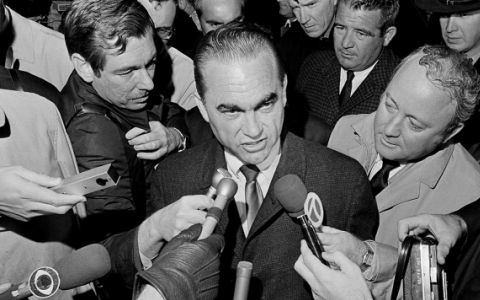

In January 1968, George Wallace, shoe-polish-black hair shining under the spotlight, threw himself into a debate over the meaning of conservatism. He was a guest on the public affairs program Firing Line, and his opponent was the show’s host — and de facto spokesman for the American right — William F. Buckley Jr. Wallace had known he would face a hostile interrogator, but for a politician who fed on anger the promise of conflict was all the more reason to participate.

Viewers looking forward to a verbal tussle were not disappointed “You are using the rhetoric of conservatism for illicit ends,” Buckley charged, depicting the country’s foremost segregationist as a New Dealer who had turned against the Democrats only when civil rights moved onto the national agenda. “I have as much rapport with the voters as any of these so-called conservatives that you talk about,” Wallace insisted, underscoring his connection with the common man by hitting the “t” in rapport. Definitions of right and left blurred in the back and forth, with Buckley complaining that an “impostor” was “forcing me to sound like a liberal, which has never happened to me before in my entire life.”

For all the heat generated by their clash — Buckley, leaning back with one arm crushed against his chair, another cocked above his head; Wallace turning his attention to the audience, trying to enlist them against his patrician antagonist — the question of what it meant to be a conservative went unresolved, an argument between the two men that continued as the credits rolled.

Until recently, historians believed they had resolved this dispute. What began in the 1990s with a trickle of articles lamenting the absence of studies on American conservatism grew in the 2000s to a flood of monographs on the activists, intellectuals, and politicians who bent history’s arc to the right. Lisa McGirr’s trailblazing study of Orange County’s suburban warriors, Bethany Moreton’s exploration of the politics of Wal-Mart, and Angus Burgin’s meticulous reconstruction of the winding path from Friedrich Hayek to Milton Friedman were just a few of the highlights in a booming field.

As Buckley would have preferred, the representative figure in this scholarship was not George Wallace but Ronald Reagan. The 40th president stood for a coalition of prosperous, forward-looking voters motivated by sincere ideological commitments and assisted by an emerging conservative establishment filled with adept manipulators of Washington’s bureaucracy. The populism and racism that fueled Wallace’s career were not forgotten, but too great an emphasis on these subjects did not fit with the grudging respect these generally liberal historians evinced for the subjects of their research.

Jason Stahl’s Right Moves is a characteristic product of this approach. Stahl, a historian at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities, describes his book as an examination of conservative think tanks, those curious institutions that, although little known to the wider public, play a decisive a role in shaping policy. Several fine studies of these organizations already exist, but they are chiefly the work of journalists, and a historical appraisal is long overdue.

Stahl’s chief object of inquiry is the American Enterprise Institute, or AEI. Founded in 1938 by a group of businessmen devoted to unwinding the New Deal, its true history began five years later, when its headquarters moved from New York to Washington. Inside the Beltway, AEI staffers portrayed themselves as nonpartisan scholars eager to assist lawmakers from both parties. That stance became increasingly difficult to maintain as the conservative movement grew in strength, and in the 1970s AEI was reborn as a champion of the right in the battle for ideas.

Success bred imitators, and AEI soon found itself outflanked by an upstart known as the Heritage Foundation. More concerned with passing legislation than posing as researchers, Heritage became the dominant think tank in Reagan’s Washington. These nimble practitioners of war-by-briefing-books made AEI seem musty and academic by comparison. AEI revived itself by shifting toward the middle, but it never regained its former centrality. It had changed too much, and so had conservatism.

Stahl narrates this history with subtlety, neither condescending to his subjects nor shielding them from embarrassment; they are at once dexterous navigators of the political scene and authors of a harebrained Heritage report holding that an increase in the number of working mothers could lead to a rise in dwarfism. His grasp of the dynamics at work in the shifting fortunes of AEI and Heritage — a relationship bound up with both sweeping political change and the intricacies of fund-raising — flows from his mastery of this milieu.

Yet Right Moves becomes less steady as it moves toward the present. Braving the risks of contemporary history, Stahl loses access to the archives that give his earlier chapters their depth and nuance. He concludes with an uncharacteristically blunt assessment of current politics. Think tanks like Heritage, he writes, have redefined what it means to be on the right and persuaded countless Americans to join their cause, managing to “forever alter American political culture in a more conservative direction.”

That was a powerful argument when this book went to press, and it would have gained even more force if conservatives were about to deliver the Republican Party’s presidential nomination to Ted Cruz. Or Marco Rubio. Or Jeb Bush. Or any of the 13 other major candidates for the position except Donald Trump. In the words of Buckley’s National Review, Trump is “a philosophically unmoored political opportunist who would trash the broad conservative ideological consensus within the GOP in favor of a free-floating populism with strong-man overtones.” But as Trump has more recently observed, “this is called the Republican Party. It’s not called the Conservative Party.” And Republicans have capitulated to a candidate opposed by the assembled forces of the conservative establishment — an establishment that is clearly as detached from the constituents it claims to represent as any of the liberal elites it has pilloried for decades, and whose isolation from its supposed base made Trump’s nomination possible.

Republicans are now wrestling with the implications of this turn; historians will move at a slower pace, but they also have a reckoning ahead. A generation ago, explaining the power of the American right seemed an essential task for anyone seeking to understand the headlines. Recent events suggest that scholars should adopt a more skeptical attitude toward the image presented by the self-appointed gatekeepers of True Conservatism. The gap between policy makers and the grassroots is larger than students of the right have allowed, the opportunities for ideological crosscutting more prevalent. Histories written from this perspective would be less willing to take Buckley at his word, and they would have more room for Wallace.

Though reeling at the moment, however, Buckley’s political descendants should not be counted out. Just a few months ago, a meeting off the coast of Georgia brought together figures ranging from Tim Cook to Karl Rove in a two-day session dedicated to mapping out a plan to stop Trump. They lost this round, but the fight will continue in the years to come, and support from organizations like the host of this conclave will be invaluable. What form this campaign will take is still a mystery. Attendance in Georgia was invitation only, as is the custom at the “American Enterprise Institute World Forum.”

Timothy Shenk, a Mellon postdoctoral fellow at Washington University in St. Louis, is the author of Maurice Dobb: Political Economist (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). This article appeared in the Chronicle of Higher Education