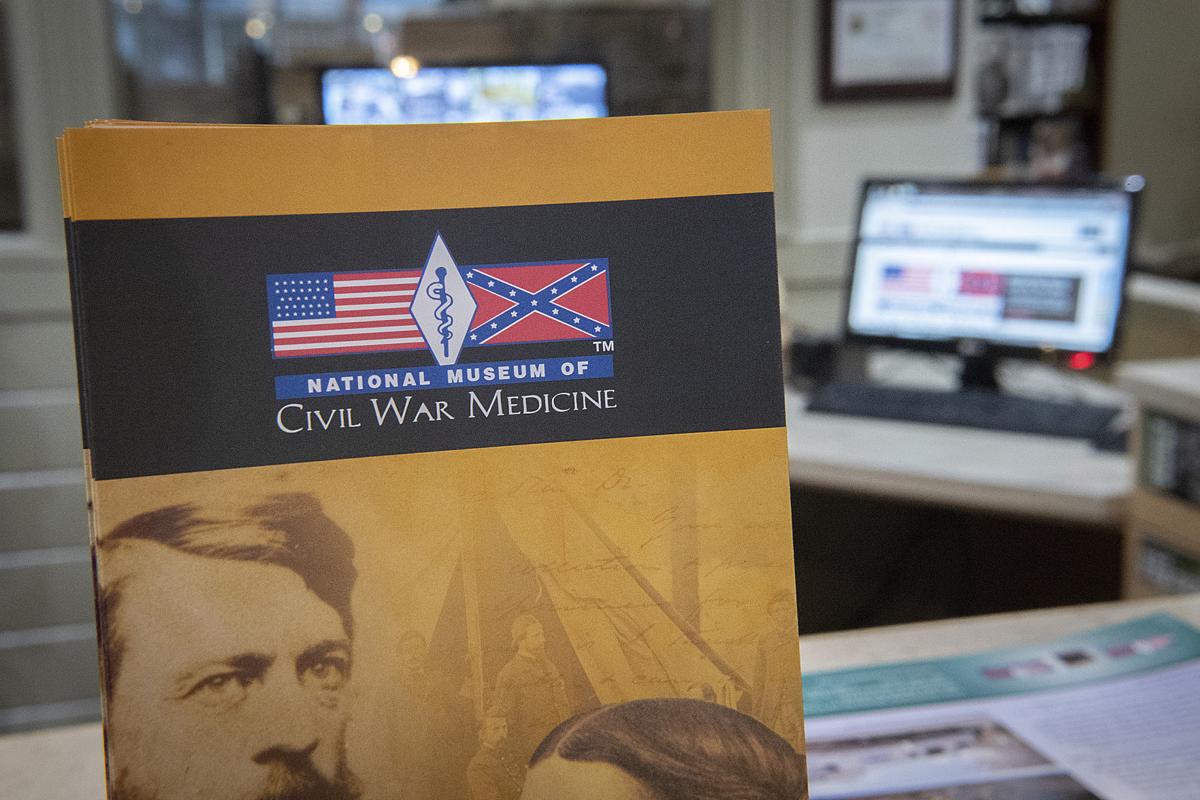

WASHINGTON, D.C. — National Civil War Museum Considers Logo Change

The logo for the National Museum of Civil War Medicine courted controversy once before.

In 2016, the Washington, D.C. tourism organization Destination DC declined to publish an ad for the local museum in its “Official Visitors Guide,” citing the Confederate flag that shares space with a Rod of Asclepius — a traditional Greek medical symbol — and a 33-starred Union Flag.

“Through that conversation, I remember them saying that the only place where a Confederate flag is appropriate is in a museum,” said David Price, the executive director for the museum. “Well, we’re a museum. So, I said I respected their right not to publish it, but they had to respect my right not to change it.”

Over the past three years, his thinking has evolved.

“A couple of years ago, I felt this was the perfect logo for this place,” Price said.

But the National Museum of Civil War Medicine has evolved, too. In 2005, the organization partnered with the National Park Service to manage the Pry House Field Hospital Museum in Keedysville, Maryland. In 2012, it assumed operational responsibility for the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum in Washington, D.C. Now, the museum encompasses three different sites with three different historical focuses, expanding beyond its initial concentration on the convergence of soldiers and medical personnel in Frederick after the battles of Antietam, Gettysburg and Monocacy.

The Confederate flag has also become a point of national contention as it’s wielded by white nationalist groups, and as a growing list of states remove their Confederate monuments. Price can remember high-level visitors to the museum decline mementos that feature the current logo. He’s received emails that express discomfort with the Confederate imagery.

“It’s the elephant in the room,” he said. “And the worry becomes, ‘Am I actually alienating an entire audience that might have come into the museum otherwise?’”

Changing the logo — or at least the possibility of it — is a new focus as the museum embarks on a rebranding campaign, funded by a capacity-building grant from the Ausherman Family Foundation. The $25,000 gift allowed museum officials to hire the Invictus Group, a marketing organization that’s working to “figure out the identity of the museum,” in the words of creative director Jeff Beck, “and figure out where we’re going to go from there.”

To start, Beck launched a public survey available through the homepage of the museum. The first page of questions largely revolves around the site itself — how guests would rate their experience, what makes the museum unique, and whether they would recommend it to a friend.

But the second page focuses on the logo itself, and especially the battle flags. “Should Union or Confederate battle flags be featured in the logo?” one question asks. “In your opinion, what does the Confederate battle flag stand for?” asks another (respondents can check multiple choices, including “southern heritage,” “history,” “slavery” and “racism.”)

Price emphasized that the museum would be working on a rebranding campaign regardless of the logo. Operating three different sites with three different emblems is confusing, he said, both for guests and from a branding perspective.

“We’d be doing this even if our logo was a circle, a square and a triangle,” he said.

Beck similarly called the logo “dated” and “dysfunctional, at best.” Both men agreed that the best course of action could be to create one unifying logo for all three sites, with the possibility of introducing separate branding later on.

“We’re really looking at whether it’s appropriate to include either of those two flags,” Beck said. “I don’t think it’s a compelling enough visual to tell the full story. What we’ve identified is that the museum’s unique focus is on medicine and what medical advances have meant for our society. And that leaves a lot of room for interpretation.”

Still, the museum’s solicitation for public feedback doesn’t sit well with members of the public who don’t think the logo should be changed at all.

Steven Berryman heads the Frederick-based Confederate Monuments Protection Society on Facebook and called the survey a “gutless move,” especially given the Confederate flag’s prominence in American history.

“It shouldn’t be a public decision,” he said. “I don’t care what public opinion says. Whether something is deemed to be historically significant or not should have nothing to do with whether people find it insensitive.”

Opponents of the current logo, which include the Frederick chapter of Showing Up for Racial Justice (or SURJ), the inclusion of the Confederate flag is concerning.

“We don’t feel like it’s a great thing to have a Confederate flag posted on the outside of a building for any reason,” said member Lisa Bromfield, “even though some people still see it as a historical symbol.”

SURJ members commended the museum for soliciting public feedback and considering a change. But Willie Mahone, the president of the Frederick NAACP, agreed with Berryman that the logo shouldn’t be influenced by public opinion. For much different reasons.

“I’ve found it objectionable for a long period of time,” Mahone said. “And public sentiment doesn’t change that. If the flag is a symbol of racial hatred and white supremacy — which we hold that it is — I don’t think they should make a decision based upon what the public says. There was once public sentiment that women shouldn’t participate in the electoral process. There was once public sentiment that Native Americans should be driven off their land. In the end, it’s a question of morality. And if the public sentiment is amoral, we should not consider it.”

–fredericknewspost.com