Alabama: Bedford statue still stirs controversy

BIRMINGHAM, Alabama (Reuters) – Racist, murderer, or savior of the town? Nathan Bedford Forrest still stirs controversy in Selma, Alabama, where emotions are running high over plans to replace a monument honoring the Civil War officer and Ku Klux Klan founder.

A bust of Forrest was stolen from a cemetery in the city in March and when the Friends of Forrest raised money to replace it, opponents gathered 84,000 signatures to stop them.

In August, protestors laid in front of trucks to prevent the statue from being installed, said civil rights lawyer Rose Sanders, who founded The Museum of Slavery and the Civil War in Selma.

Protestors now plan to march on the cemetery on Friday, then drive to a church in Birmingham, some 85 miles away, where four children were killed in 1963 by a bomb set by Klan members, said organizer Sanders. The protestors are part of a local group called Grassroots Democracy.

“Would people tolerate a statue of bin Laden or a Nazi? I know of no one in U.S. history less deserving of a monument,” said Sanders.

More than 10 years ago, the Friends of Forrest placed the original statue at the Selma historical museum, then moved it to the cemetery where Confederate veterans are buried. The acre of land on which the cemetery stands was granted by the city in 1877 for a Confederate memorial.

A $10,000 reward has failed to coax the statue’s return.

The African-American mayor of the majority black city has declined to revoke a building permit held by the Friends of Forrest.

“We thought it would be good for tourism. Our Civil War and Civil Rights history brings a lot of people to Selma,” said Steven Fitts, a local historian and member of Friends of Forrest.

Civil War and civil rights history are juxtaposed in Selma. Protestors were killed there in 1965 during a march from Selma to Montgomery that came to be known as “Bloody Sunday” and sparked the Voting Rights Act. Before the Civil War, the city was called the “Black Belt of Alabama” because of its rich soil.

Fitts said the riverfront town was saved by Forrest during the war when, as a lieutenant general in the Confederate Army, Forrest and his mounted troops kept the city from being burned by the Union army. After the war, he is credited with founding the Ku Klux Klan and was its first leader.

“Hundreds of people, thousands of people were killed in the South by the Klan. Why allow a statue of a domestic terrorist?” Sanders asked.

Fitts disputes Sanders’ view of Forrest’s record, claiming the one-time slave trader disbanded the Klan after it became violent. “She just wants one-sided history,” he said. “I don’t think she has a right to extinguish anyone else’s history. There is no reason that one has to exist without the other.”

###

Maryland: Many Sharpsburg homes have Civil War history

By DON AINES | dona@herald-mail.com

SHARPSBURG, Md. — With thousands of dead on the field of battle and thousands more wounded, almost every home and building in Sharpsburg that wasn’t being used as a Confederate defensive position during the Sept. 17, 1862, Battle of Antietam became a makeshift hospital, where many Union and Confederate soldiers drew their last breaths.

Some of those houses have stories — some possibly apochryphal or embellished — and many still bear the physical scars 150 years after the bloodiest day in American history.

Oral history “is a little like that game where you whisper in someone’s ear and it goes around in a circle,” the original story changing as it passes from one person to another, said Rosita Ray, the current owner of the Piper House on East Main Street in Sharpsburg.

Walking through the rooms of the Piper House, Ray pointed out the bullet damage to doors and window frames. The nose of a lead bullet protrudes from a window frame and the end of another can be seen half buried in a door.

The hole made by a cannonball is gone, Ray said. A craftsman was hired to refurbish the stone wall, but she forgot to tell him not to fill in the hole, she said.

Before it was gone, birds would nest in it each year, Ray said.

The Piper House drew Union fire — collateral damage, really — because the troops were aiming at Confederates in the steeple of a long-gone Lutheran church down the street, Ray said.

The Pipers fled town during the fighting. They returned to find two dead Confederate soldiers in the dining room, she said.

Good-Reilly House

“Folks that know the battle know there was no space with a roof that wasn’t impacted by the battle,” said Brien Poffenberger, president of the Hagerstown-Washington County Chamber of Commerce and owner of the Good-Reilly House, which already was a century old when the battle was fought.

“It was just another day in a house with a history,” said Poffenberger, who has a master’s degree in architectural history and restored the house. He found structural members in the roof with burn damage, but cannot say whether that was tied directly to the battle or occurred at some other time.

The Reilly who once owned the house was O.T. Reilly, a boy when the battle was fought who later became a tour guide and dealt in souvenirs, Poffenberger said.

Bayonets, canteens and other artifacts often were plowed up from fields in the decades after the battle, Poffenberger said.

Sharpsburg does not have a designated historic district, so maintaining the character of the houses and commercial buildings is up to the owners, said Vernell Doyle, president of the Sharpsburg Historical Society.

Many of the buildings along the town’s eight streets predate the Civil War, but they are also people’s homes, and owners view them as such.

“Depends on what you mean by historic,” one man said of his home, noting he was unaware of any connection his home had with the Battle of Antietam.

Built in 1854

“The cannonball holes in the wall,” Kathleen Boyer said when asked what connection her Chapline Street home had to the battle. Stepping around to the east side of the house, she pointed to five places where the brick work was damaged.

Boyer has lived in the house all of her 78 years and it has been in her family since ancestor Frank Gloss built it in 1854. His initials and the year are scratched into one of the bricks.

“The only things that aren’t original are the steps and the door,” Boyer said. Even the peony bushes in the back are more than a century old, she said.

Living with history is not unusual if it is all you have known, Boyer said. The town’s fame does not often intrude on her privacy, but there have been times.

“What irks me is people have come in with metal detectors without permission. Until I catch ’em,” she said.

Boyer said she has found souvenir hunters trying to dig up artifacts in her yard.

Restoration project

Next door, Clay and Jacqueline Herzog have been in the process of restoring a cut stone house for several years.

“I started out thinking it was going to occupy me for about two years,” Clay Herzog said.

That was four years ago, he said, and the end is not in sight.

The street frontage of the house looks much as it would have during the war, but the Herzog’s have built an addition to the rear. As much as possible, in materials and architecture, they have tried to keep it in character with other historic buildings, he said.

Clay Herzog’s deed searches have taken the building back to at least 1853, but he suspects it goes back much further, having been among the first lots sold by Sharpsburg’s founder, Capt. Joseph Chapline in 1764.

“It had been abandoned for 25 years” and dilapidated when they bought it, Herzog said.

The story for this house is that when the owners returned after the battle, they found a wounded Confederate soldier wrapped in a quilt on the stoop, Clay Herzog said. The quilt was donated to the Washington County Historical Society, he said.

Barbara Morrow’s family hid in a cave along the Potomac River and returned to find the soldier, according to historical society records cited by Registrar Cathy Landsman.

Kretzer House

During the battle, many Sharpsburg residents fled their homes and the town, but some sought shelter in the Kretzer House.

“We had a spring in the cellar and that’s where the townspeople congregated when the soldiers were fighting,” said Maryanna Munch, who lives in the Kretzer House on East Main Street. “The basement has three rooms, so I imagine it can hide quite a few.”

Munch’s roots in Sharpsburg go back quite a ways, she said.

“My mother was a Kretzer,” she said.

The lady of the house at the time of the battle was Teresa Kretzer. Confederate soldiers coming through town ordered her to take down an American flag that flew at the house, Munch said. When the soldiers returned, she told them “it was in ashes,” Munch said.

In fact, Teresa Kretzer did not burn the flag, but hid it under fireplace ashes, Munch said.

Biggs House

The Biggs House on West Main Street was the home and office of Dr. Augustin A. Biggs during the war years. The gable side of the house, now owned by Sid and Marian Gale, has shell damage, with a cannonball displayed where it struck.

Marian Gale said the original cannonball was removed years ago by a previous owner and she had another put in its place.

The Stone Houses of Sharpsburg Walking Tour pamphlet produced by the Sharpsburg Historical Society notes that another shell went through a window into the dining room and that a Confederate soldier sitting in the doorway was killed by a stray bullet.

The street frontage, with the original carriage stones and hitching post, and the front rooms of the house look much as they would have in the 19th century, down to the furnishings. The bloodstains on the living room walls and floor have been painted over, Gale said.

Their son, Peter Gale, said that occupying the house is a bit like living in a museum. He recalled inviting some college friends over and telling them the family had an antiques shop on the property.

“So where’s the house?” one of them asked upon entering the home, he said.

###

Tennessee: Civil War Trust buys more property for Franklin’s battlefield

By Kevin Walters, The Tennessean

FRANKLIN – History books, real-estate listings and cash are again saving part of Franklin’s Civil War battlefield.

Civil War veteran descendent Sam Gant stands along the less than half-acre vacant property recently purchased by the Washington, D.C.-based Civil War Trust. The land, where the first shots of the Battle of Franklin caused casualties, was bought for little more than $135,000. / Kevin Walters/THE TENNESSEAN

On the night of Nov. 30, 1864, the first shots of the Battle of Franklin erupted and claimed the firefight’s first casualties, who happened to be Federal troops standing along what is present-day Columbia Avenue. Ultimately, the short, brutal Battle of Franklin would claim 8,500 casualties in a few hours’ time.

Today, the land where those first soldiers fell is an empty, less than half-acre lot that owner Richard Dooley had for sale.

Dooley’s plans have changed. Alerted by a local historian who saw the land was up for sale, the Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit Civil War Trust stepped in and contacted Dooley who’s sold it to them. The deal will cost $135,480, which includes closing costs.

“I didn’t think anybody would be interested in it,” said Dooley, 74, a custom home builder who lives in Thompson’s Station. “I’m very glad to see this piece of property go to them.”

The purchase further deepens the Civil War Trust’s investment in Franklin where the group has used more $4 million in grants and pledges since 2005 to buy battlefield land. As recently as last year, the trust raised $200,0000 to buy about 5 acres of the former battlefield along Adams Street in Franklin.

Once overlooked because of decades’ of development, the recent purchases of battlefield land have raised Franklin’s profile among historians and open space preservationists. That standing will likely only increase in the years leading up to the unveiling of a new Columbia Avenue battlefield park that the trust and private donations have helped acquire.

“This is an amazing story of a community that is acre by acre — or in this case, half-acre by half-acre — reclaiming its history,” said Mary Koik, trust spokeswoman.

Final details of the transaction are still being settled but it should be completed in the next few weeks. City of Franklin officials have agreed to have the city act as a pass-through agency for the money because the trust is using around $67,000 from the federal American Battlefield Protection Program.

News of the sale and its swiftness came as a pleasant surprise to longtime Franklin battlefield preservationists like Sam Gant and Sam Huffman. Gant and Huffman have known about the property’s importance for years, but didn’t have the resources to buy it.

But the trust has the money and the manpower, counting more than 55,000 members who can make donations to buy land it’s available, said Mike Granger, the trust’s vice-chairman. The Civil War Trust has maintained its membership count as the U.S.’s largest Civil War preservation group even during the recession when many nonprofits saw their membership numbers decline.

“We are able to move fast on most of these transactions,” said Granger, who is also a Franklin resident. “We have money available for a transaction like this that our members have given us over the years.”

Connections on the ground also help the trust find property when it’s for sale.

Eric Jacobson, chief operating officer of the Battle of Franklin Trust, happened to see Dooley’s “For Sale” sign and contacted the trust two months ago. Empty battlefield land at a good price was too good an offer to pass up.

“It was priced right, and it was available. It was just kind of a no-brainer,” Jacobson said. “We can say there were troops on this ground when the first casualties were inflicted.”

###

Texas: Finding Civil War Fort Magruder

By Michael Barnes, Austin-American Statesman

It started with a street sign. It ended with a stroll around the grounds of an abandoned Civil War fort in South Austin.

You didn’t know Austin — far from any battlefield — played a part in Confederate defenses? In fact, slave labor built three forts around Austin to ward off possible invasions from the south, north and east.

Two decades ago, I noticed a street sign off South First Street, just north of the former discount store that now serves as a (sigh) Chuck E. Cheese outlet. It pointed to the narrow Fort Magruder Lane. Nearby is military-sounding Post Road Drive.

Now I’m no Civil War buff, but why hadn’t I heard of Fort Magruder while reporting on the people, places and scenes of our fair city? Questions to longtime residents drew blanks. Published references were few and far between.

Six months ago, though, while looking into Travis Heights for a Real magazine profile, I stumbled across a history of South Congress Avenue in an online report first published in the 1990s, when improvements were considered for what would become known as SoCo. (Years earlier, architect Emily Little had given me a print version of the report, but clearly I didn’t read it too carefully. A clue ignored.)

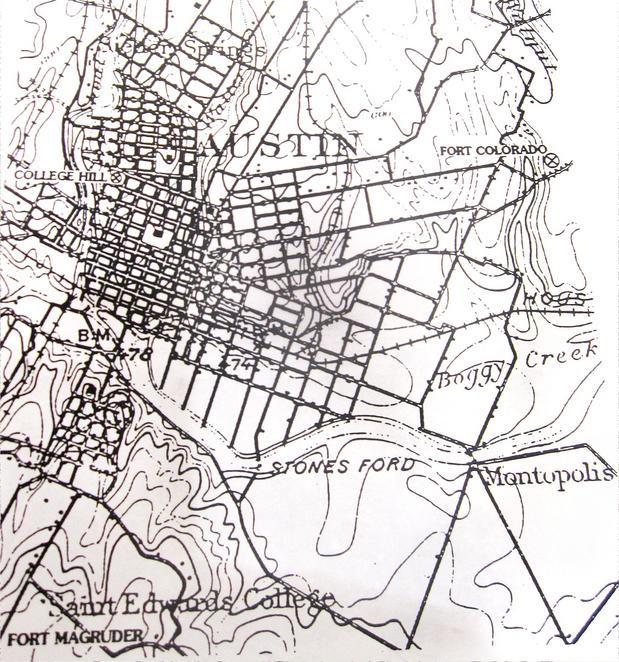

Anyway, that report showed the precise location of trenches and a dugout near the northwest corner of South Congress and Ben White Boulevard. The fort’s plan — which looks something like the silhouette of the Starship Enterprise — lay alongside Wadford Street below Dunlap Street. Wow! It existed, I thought.

Two weeks ago, taking time off from another project, I requested materials on Fort Magruder at the Austin History Center.

Two yellowed pages referred to “Fortview,” an 1875 subdivision laid out around the fortifications. One reproduced the original subdivision plat and the other was a 1956 newspaper article about the City of Austin charging a “tap fee” to link the rural area to its urban sewer system. (Consider that in my lifetime, this area at the headwaters of East Bouldin Creek was way out in the country. Now condos and apartments south of there boast of “downtown living.”)

The gold mine of material, however, is a bound 1995 Texas Department of Transportation report written by John Clark Jr. and David Romo. This survey of archeological and archival evidence was put together quickly, since TxDot was already in the process of turning Ben White into a freeway.

The fort was built in December 1863 and January 1864 as Confederate leaders panicked about Union incursions into Texas. Major Gen. John Magruder, who earlier had battled Union Gen. George McClellan during the Peninsula Campaign in Virginia, was then in charge of the military district that included Texas.

When Galveston, the state’s main city and port, was briefly captured by Union troops, Confederate soldiers retreated inland. Even after it was recaptured, Texas leaders wavered on how to defend the capital city. In November 1863, Union forces took lightly defended Brownsville, and it appeared as though an expeditionary force would sweep up from the Rio Grande Valley.

As many as 1,000 slaves were drafted from as far away as La Grange to build defenses on the San Antonio to Austin road, which became South Congress Avenue. Neither plantation owners nor Austin residents were happy with the arrangements. Local white women called the billeting of the slaves in an Austin church “barbaric.” As usual, the African-Americans got the worst of it.

“They were half froze since the winters of 1863 and 1864 were cold ones,” wrote engineer Major Julius Kellersburg. “We had 11- to 12-degree weather and naturally no winter clothing.”

During an interview conducted in the 1930s, former slave John Walton remembered panic in the face of what seemed like an imminent Yankee attack. The emergency ended when Union troops focused instead on reaching the Texas interior via the Red River.

After that, the northern boundary of Fort Magruder’s grounds turned into Post Road Drive, while the southern line became Radam Lane, south of Ben White. East-west, the full fort stretched from South First to South Congress. The unfinished defenses filled with trash.

A Chamber of Commerce pamphlet from the 1930s reported: “These large trenches and the dugout are still plainly visible.”

The TxDot conclusion after the 1990s excavation: No Civil War-era artifacts were found. The only remaining 19th-century structure near the site, a house occupied by transients, burned to the ground.

(About the time I started asking questions in 1992, reporter Stuart Eskenazi wrote a focused piece about TxDot’s early archival work on Fort Magruder for the American-Statesman, but I didn’t run across his article until this week. Reporters: Always start your research in your own archives.)

Last week, I walked our dog down to Fort Magruder. Although there’s a man-made cut in the knob above Dunlap Street, there are no signs of trenches or earthworks.

Wait! The TxDot report included a turn-of-the-century map showing two other Confederate forts. One rose at College Hill somewhere around the corner of West 15th Street and West Avenue. The other, called Fort Colorado, and later Fort Prairie on maps, stood off Webberville Road just east of Heflin Lane, near the wooded area where Austin Wildlife Rescue now operates.

To my knowledge, neither site has been excavated.

###