Mississippi: For Miss., an angst-filled Civil War Anniversary

By EMILY WAGSTER PETTUS – Associated Press

JACKSON, Miss. — Commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Civil War can be an angst-filled task in Mississippi, with its long history of racial strife and a state flag that still bears the Confederate battle emblem.

Well-intentioned Mississippians who work for racial reconciliation say slavery was morally indefensible. Still, some speak in hushed tones as they confess a certain admiration for the valor of Confederate troops who fought for what was, to them, the hallowed ground of home and country.

“Mississippi has such a troubled past that a lot of people are very sensitive about commemorating or recognizing or remembering the Civil War because it has such an unpleasant reference for African-Americans,” said David Sansing, who is white and a professor emeritus of history at the University of Mississippi.

“Many Mississippians are reluctant to go back there because they don’t want to remind themselves or the African-American people about our sordid past,” said Sansing. “But it is our past.”

Black Mississippians express pride that some ancestors were Union soldiers who fought to end slavery, though it took more than a century for the U.S. to dismantle state-sanctioned segregation and guarantee voting rights.

Sansing is among dignitaries traveling to Antietam National Battlefield in Sharpsburg, Md., this weekend to dedicate a blue-gray granite marker commemorating the 11th Mississippi Infantry, which saw 119 members killed, wounded or missing in battle there on Sept. 16-17, 1862. The infantry had almost 1,000 soldiers, including a unit of University of Mississippi students known as the University Greys.

Among the speakers set to dedicate the monument Sunday is Bertram Hayes-Davis, great-great grandson of Confederate president Jefferson Davis. He was recently hired as executive director of Beauvoir, the white-columned Biloxi, Miss., mansion that was the final home of his ancestor, a Mississippi native.

The state is taking a decidedly low-key and scholarly approach to commemorating the sesquicentennial of the Civil War.

Re-enactments have taken place at battlefields near Tupelo and are planned soon near Iuka. Lectures, concerts and other gatherings are scheduled over the next several months. Several events are expected in 2013 to mark the 1863 siege of Vicksburg, which gave the Union control of the Mississippi River.

Mississippi is the last state with a flag that includes the Confederate battle emblem, a red field topped by a blue X with 13 white stars. The symbol has been on the state flag since 1894. In a 2001 statewide election, voters decided nearly 2-to-1 to keep it, despite arguments it was racially divisive and tarnishing the state’s image.

With a population that’s 38 percent black, Mississippi has elected hundreds of black public officials in the past four decades – a change directly linked to the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Many people, across racial lines, say it’s important that Civil War history commemorations not turn into celebrations of a lost cause.

Derrick Johnson, state president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, said generations have been taught a “revisionist history” of the Civil War that ignores or downplays the impact of slavery. He said he wants a full discussion of the war.

“In mixed racial company, people don’t want to address race and there is truly an avoidance of conversation when it relates to history and race,” Johnson said. “Civil War, pre-Civil War, Reconstruction, Redemption, segregation – nobody wants to have candid conversations about how the past affects the public policy of this state and how people of different races interact with one another in this state.”

RALEIGH – Heroic tales and valiant feats are depicted in images that reflect North Carolina’s dedication to the war in the Freedom, Sacrifice, Memory: Civil War Sesquicentennial Photography Exhibit. The Shepard-Pruden Memorial Library in Edenton will host the exhibit from Sept. 1-28, sharing images and stories that capture the history and people of the Civil War (1861-1865).

“The Civil War was the first war widely covered with photography. The Freedom, Sacrifice, Memory exhibit provides images of historic figures, artifacts, and documents that brought the reality of the war from the battlefront to the home front, then and now,” explains Deputy Secretary Dr. Jeffrey Crow of the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources.

The N.C. Department of Cultural Resources will display 24 images from the State Archives, the N.C. Museum of History and State Historic Sites. Between April 2011 and spring 2013, 50 libraries and four museums will showcase “Freedom, Sacrifice, Memory” offering visuals that present gallant women, African American triumph and the perseverance of Confederate soldiers. A notebook will accompany the exhibit with further information and seeking viewer comments.

One of the images is a portrait of Parker D. Robbins, who grew up in a community known as the Winton Triangle along the Chowan River, and joined the U.S. Colored Troops during the war. Robbins represented Bertie County in the House of Representatives after the war, and later moved to Duplin County where he was a builder and inventor.

The unique exhibit will share the history from regions across North Carolina, and educate viewers about the hardships and resolve of North Carolinians during this pivotal time in United States history.

For information on the hours call (252) 482-4112. For tour information visit the North Carolina Civil War Sesquicentennial website or call (919) 807-7389.

South Carolina: Archaeologists Map 55 Civil War Wrecks in Charleston Harbor

By Matt Long, South Carolina Radio Network

Archaeologists from the University of South Carolina have wrapped up a five-year survey of the Charleston Harbor as they try to map out the 55 Civil War shipwrecks that cover its floor. It’s the first time that historians have ever mapped out the complete naval battlefield for the siege, which lasted from 1861 to 1865.

Underwater archaeologist James Spirek of the South Carolina Institute and Archaeology and Anthropology (SCIAA) helped lead the project on behalf of the National Park Service. “If we don’t know where the (artifacts) are, we can’t help protect them,” he told South Carolina Radio Network.

Most South Carolinians know that the Civil War began in the harbor with the Confederate shelling of a U.S. garrison at Fort Sumter in 1861. Later that year, the Union Navy began blockading the harbor in an effort to prevent supplies from reaching the South. There were also two naval attacks on the city before the war ended four years later.

Spirek used official records of the armed forces, along with 19th-Century charts, to help map out the modern locations of the wrecks. The team then used remote sensory equipment that could detect iron to find the exact coordinates. They then used side-scan sonar to image the ocean floor and detect any objects that could be sticking out from it.

Roughly half of the wrecks (29) are old whaling vessels that the Union Navy sank to block the entrance of the harbor. Known as the “Stone Fleets,” some of these vessels’ exact locations had been a mystery for decades until the SCIAA survey. “Most people thought they were buried under the sandbars, but apparently, they’re still exposed on the bottom of the harbor floor,” Spirek said.

Spirek said 16 of the wrecks his team identified were “blockade runners”— Confederate merchants who tried to avoid the Union ships and supply the city. Four federal warships and six Confederate vessels also lie beneath the waters.

The National Park Service approved a $28,000 grant for the project in 2008, which was matched by an additional $28,000 from the University of South Carolina.

Spirek was also able to locate several of the Union ironclad ships, known as “monitors,” by using previous survey reports and sonar technology and magnetometers.

These included the Patapsco, sunk by a mine near Fort Sumter; the Weehawken, which flooded in a storm; and the Keokuk, an experimental ironclad that sank after a severe pounding by Confederate artillery. Specific GPS coordinates were assigned to each wreck for future investigation.

The USC survey took nearly as long as the battle did more than a century ago, but the results are worth it, Spirek said.

MANASSAS, Va. — The Civil War Trust is rolling out a new “battle app” to mark the 150th anniversary of the Second Battle of Manassas.

The battle application making its debut Tuesday includes video featuring top historians and topographical maps, among other features. The free smartphone application is the latest in a series developed by the trust on key Civil War battles.

Others explore the battles of Bull Run, Cedar Creek, Chancellorsville, Fredericksburg, Gettysburg and Malvern Hill. The trust says more than 60,000 people have downloaded the trust’s battle apps.

The apps are created with funding from the Virginia Department of Transportation and created in partnership with NeoTreks, a leader in mobile GPS-based touring.

Online:

Civil War Trust Battle Apps: http://www.civilwar.org/battleapps

VIENNA, Va., August 29, 2012 — The Civil War has often been referred to as being “brother against brother,” and in truth there are many stories of biological brothers serving against each other, one for the United States and one for the Confederate States.

The story of the large, unique statue at Gettysburg National Cemetery, Gettysburg, Pa. reflects the love and devotion of two brothers who shared neither father nor mother and by any normal description were not brothers. In a very real sense, however, they were, and the statue stands today to commemorate their love.

Confederate Brig. Gen. Lewis Addison Armistead was born in New Bern, N.C. and was a member of Alexandria-Washington Masonic Lodge # 22. Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, a Union officer, was born in Norristown, Pa. and was a member of Charity Lodge # 190 of that town. The two shared a friendship that had gone back for many years until politics of the time caused them to go separate ways.

Friends Choose Different Paths

The two men were stationed in California when the War began. Armistead’s sympathies lay with the Southern cause and he resigned his commission in the U.S. Army to become a Confederate Officer. Hancock was a staunch Union man and went East to join the Federal ranks there. Both men served capably and well and were promoted into their respective leadership roles.

During war, time passes rapidly amidst the powder and smoke of battle, and it would be twenty-seven months before they would meet again. It happened on the bloody battlefield known as Gettysburg, on July 3, 1863, when Pickett’s Charge took place. Gen. Armistead’s brigade formed the second rank of the attacking division. It was at Cemetery Ridge that he was mortally wounded; coincidentally Hancock also sustained serious wounds, which would keep him hospitalized for a considerable length of time.

Capt. Bingham Reacts

Hancock had an aide with him, Capt. Henry Harrison Bingham, during the formidable battle that became known as marking the “High Tide of the Confederacy.” After Hancock had been carried from the field, it was Bingham and some other Union officers who heard the cries for help from Armistead’s lips as he lay there.

Bingham was a Judge-Advocate of Hancock’s Second Corps at Gettysburg. He had been born in Philadelphia, Pa. and also a Freemason, belonging to Chartiers Lodge # 297, Canonsburg, Pa. He had had a brilliant career, fighting at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania where he was breveted for bravery and war service, and now at Gettysburg, where he too was wounded.

Bingham recognized the distress cry of a Freemason as would have his superior, Winfield Hancock, and such a cry must be acknowledged. It mattered not if the wounded man wore Blue or Grey, he was a brother Mason, and Bingham answered the seriously injured Armistead, who talked to Bingham of his close relationship with Hancock.

“Take My Watch to Winfield”

He asked Bingham to relay a message to Hancock, his old friend and brother, and gave his personal effects including a pocket watch, to the captain. Bingham promised to get them to Hancock, giving Armistead what help and assistance he could, until the General was taken from the field. He would die two days later at a hospital on the George Spangler farm site, comforted by the fact that his personal effects would go to his fraternal brother to be returned to his family.

This story has been historically verified and stands as a testament to the depth of the Masonic bonds between members even in wartime.

Another less known but similar story takes place on the same July 3, 1863 horrific date, when the Confederate forces were coming closer to the Union lines, and Sgt. Drewry B. Easley of the Confederate 14th Virginia infantry suddenly saw some Union skirmishers nearby. They were hiding, huddled in a tall wheat field and had been cut off from their retreating buddies: death was certain to happen. Then Sgt. Easley suddenly recognized a Masonic distress sign given by one of the Yankees and ordered his men to pass them by.

Munn’s Vision for the Monument

Years later, Sheldon Munn who was a former park guide at Gettysburg, and who also had written a book entitled, “Freemasons at Gettysburg,” woke early one day after having a vivid dream in which he “saw” a monument at Gettysburg, honoring the service of soldier Masons. It seemed a clear charge to Munn to see that this happened.

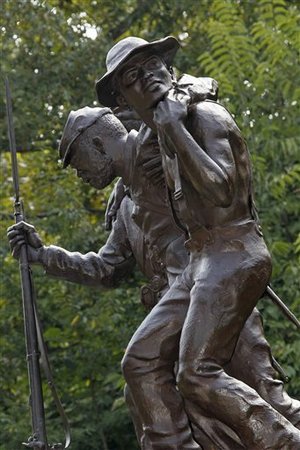

Thus was born the “Friend to Friend Masonic Memorial,” which was finally dedicated in 1993. The life-sized statue done by sculptor Ron Tunison of Cairo, N.Y. (also a Mason) depicts Bingham bending over a reclining Armistead, Bingham’s arm around the general’s shoulder, his other hand touching Armistead’s, as he receives the request from the General, who fears Union soldiers will take his personal effects if they remain with him.

The two sculpted figures portrayed atop a large granite base are a poignant testimony to the fraternal love shared by those who belong to any of the numerous similar groups where bonds make them brothers. The Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of Pennsylvania sponsored the statue,

Since the Civil War touched men and families on both sides of the Mason Dixon Line, it is not surprising that the figures indicate some eleven per cent of men on both sides were Masons and over 300 generals from both sides were Masons.

Extrapolating it further, one authority estimates that there were nearly 18,000 Masons on the battlefield, and that approximately 5,600 of them became casualties.

While many people have seen the “Friend to Friend” memorial at Gettysburg, most do not know the “rest of the story” of who is represented there and why the figures remain one of the most beloved on a battlefield, which has over 1,320 monuments and markers of every size, shape, and description.

Addendum: Later research in 2010 altered the story slightly. Bingham’s encounter with Armistead occurred while the mortally wounded Armistead was being carried from the field by several men and happened purely by chance, not because of any appeal of Masonic significance, author Michael Halleran, also a Freemason, says. Bingham never said anything different. No one is alive now who was there then, so the old story continues to live. And while it may have been a chance meeting of Armistead and Bingham, who is to say that Armistead had not given the distress signal then?

As for historian Halleran’s assertion, iconoclasts are never popular.

Follow the column on Face Book or LinkedIn at Martha Boltz, and by email it’s MBoltz2846@aol.com Read more of Martha’s columns on The Civil War at the Communities at the Washington Times.

Virginia Civil War history is on the move as the custom 18-wheel Virginia Civil War 150 HistoryMobile visits Smyth County for Labor Day weekend, Sept. 1-3. The HistoryMobile will be open from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Sept. 1 and 2 and from 9 a.m. to noon on Sept. 3. Admission to the HistoryMobile, which will be at the Smyth County Tourism Center off Interstate 81 in Chilhowie, is free.

An initiative of the Virginia Sesquicentennial of the Civil War Commission, the expandable 78-foot HistoryMobile contains a high-tech immersive experience detailing Virginia’s incomparable place in Civil War history. The exhibits were designed through a partnership between the Fredericksburg/ Spotsylvania National Battlefields Park and the Virginia Historical Society and examine Virginia’s Civil War history from the viewpoints of soldiers, civilians and slaves. The HistoryMobile is also supported by the Virginia Tourism Corporation, through which visitors can obtain information on visiting Virginia Civil War sites at the exhibit, as well as by the Virginia Department of Motor Vehicles.

The HistoryMobile draws together stories from all over Virginia and uses state-of-the-art technology and exhibits to present individual stories of the Civil War and Emancipation from the viewpoints on those who experienced it – young and old, enslaved and free, soldiers and civilians.

Visitors will encounter history in ways they may have never experienced as they are confronted in the Battlefield exhibit by the bewildering sense of chaos experienced by soldiers. The Homefront exhibit calls on visitors to place themselves in the shoes of wartime civilians and make the choices that faced Virginians of those times. The Slavery exhibit looks through the eyes of those who escaped to freedom and those who waited for freedom to come to them. The enduring legacy of the war is presented as a loss/gain scenario that challenges visitors to examine their own perspectives.

From the emotional letter written by a dying son to his father after sustaining a mortal wound at Spotsylvania in 1864 to an overheard conversation between husband and wife considering the great risks and rewards of fleeing to freedom, the HistoryMobile presents the stories of real people whose lives were shaped by the historic events of the 1860s and invites visitors to imagine and consider, “What Would You Do?”

The Civil War 150 HistoryMobile visits museums, schools, state and federal parks, fairs, and other sites. Its four-year tour began in July 2011, and it has received widespread praise. In 2011, there were more than 20 scheduled stops and a dedicated two-week tour of Southwest Virginia, and there are over 30 scheduled stops in 2012.

More information on the HistoryMobile and the Virginia Sesquicentennial of the Civil War Commission can be found at www.HistoryMobile.org. For information on visiting Civil War sites throughout Virginia go to www.Virginia.org/CivilWar.

###