In 1866, an Act of Congress created six all-black peacetime regiments, later consolidated into four –– the 9th and 10th Cavalry, and the 24th and 25th Infantry –– who became known as “The Buffalo Soldiers.” There are differing theories regarding the origin of this nickname. One is that the Plains Indians who fought the Buffalo Soldiers thought that their dark, curly hair resembled the fur of the buffalo. Another is that their bravery and ferocity in battle reminded the Indians of the way buffalo fought. Whatever the reason, the soldiers considered the name high praise, as buffalo were deeply respected by the Native peoples of the Great Plains. And eventually, the image of a buffalo became part of the 10th Cavalry’s regimental crest.

Initially, the Buffalo Soldier regiments were commanded by whites, and African-American troops often faced extreme racial prejudice from the Army establishment. Many officers, including George Armstrong Custer, refused to command black regiments, even though it cost them promotions in rank. In addition, African Americans could only serve west of the Mississippi River, because many whites didn’t want to see armed black soldiers in or near their communities. And in areas where Buffalo Soldiers were stationed, they sometimes suffered deadly violence at the hands of civilians.

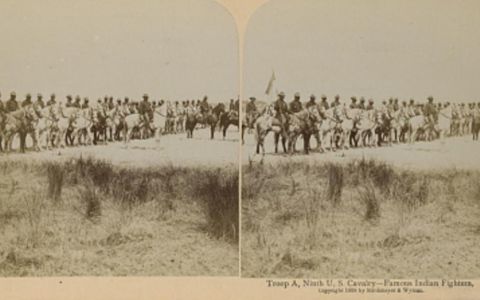

The Buffalo Soldiers’ main duty was to support the nation’s westward expansion by protecting settlers, building roads and other infrastructure, and guarding the U.S. mail. They served at a variety of posts in the Southwest and Great Plains, taking part in most of the military campaigns during the decades-long Indian Wars –– during which they compiled a distinguished record, with 18 Buffalo Soldiers awarded the Medal of Honor. This exceptional performance helped to overcome resistance to the idea of black Army officers, paving the way for the first African-American graduate from West Point Military Academy, Henry O. Flipper.

Henry Ossian Flipper was born into slavery in Georgia on March 21, 1856. During Reconstruction, he attended Atlanta University, and was then appointed to West Point by U.S. Representative James C. Freeman. Four other African-American cadets were already attending the academy, but faced enormous difficulties due to hostility from the other cadets. Flipper overcame these obstacles, and in 1877 he became the first of the group to graduate. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant, and assigned to the 10th Cavalry Regiment, becoming the first black officer to command soldiers in the regular U.S. Army. But while Flipper served with distinction, he faced intense resentment from some white officers and was targeted by a smear campaign that culminated in a court martial and his dismissal from the Army in 1882. In 1999, President Bill Clinton posthumously pardoned Flipper.

Much attention is given to the irony of African-American soldiers fighting native people on behalf of a government that accepted neither group as equals. But at the time, the availability of information was limited about the extent of the U.S. government’s often-genocidal polices toward Native Americans. In addition, African-American soldiers had recently found themselves facing Native Americans during the Civil War, when some tribes fought for the Confederacy.

Buffalo Soldiers played significant roles in many other military actions. They took part in defusing the little-known 1892 Johnson County War in Wyoming, which pitted small farmers against wealthy ranchers and a band of hired gunmen. They also fought in the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars, and played a key role in maintaining border security during the high-intensity military conflict along the U.S.-Mexico border during the Mexican Revolution. In 1918, the 10th Cavalry fought at the Battle of Ambos Nogales, where they assisted in forcing the surrender of the Mexican federal and militia forces.

Discrimination played a role in diminishing the Buffalo Soldiers’ involvement in upcoming major U.S. conflicts. During World War I, the racist policies of President Woodrow Wilson (who had already segregated federal offices) led to black regiments being excluded from the American Expeditionary Force and placed under French command for the duration of the war –– the first time ever that American troops had been put under the command of a foreign power. Then, prior to World War II, the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments were essentially disbanded, and most of their troops moved into service roles. However, the 92nd Infantry Division –– known as the “Buffalo Division” –– saw combat during the invasion of Italy, while another division that included the original Buffalo Soldier 25th Infantry Regiment fought in the Pacific theater. The last segregated U.S. Army regiments were disbanded in 1951 during the Korean War, and their soldiers were integrated into other units.

While renowned for their fighting abilities, the Buffalo Soldiers were also recognized for their exceptional horsemanship. Black non-commissioned officers of the 9th Cavalry began training West Point Cadets in riding skills and tactics from 1907 until 1947. The Buffalo Soldiers served as some of the first national park rangers when the U.S. Army served as the official administrator of Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks between 1891 and 1913. They protected the parks from illegal grazing, poachers, timber thieves and wildfires. They also oversaw the construction of park infrastructure, including the first trail to the top of Mount Whitney –– the highest mountain in the contiguous U.S. –– and the first wagon road into Sequoia National Park’s renowned Giant Forest. While most of their officers were white, Charles Young, the third African-American graduate of West Point, served as Acting Military Superintendent of Sequoia and General Grant National Parks –– the first African-American national park superintendent. During his tenure, he named a Giant Sequoia for Booker T. Washington, and another Giant Sequoia was named in Young’s honor in 2004.

On September 6, 2005, Mark Matthews, the oldest living Buffalo Soldier, died at the age of 111. Today there are monuments honoring the Buffalo Soldiers in Kansas at Fort Leavenworth and Junction City. They have also been immortalized in popular culture through songs like reggae giant Bob Marley’s “Buffalo Soldier,” television productions like 1997’s Buffalo Soldiers starring Danny Glover, and in films like Spike Lee’s Miracle at St. Anna, which chronicles the Buffalo Soldiers who served in the invasion of Italy in World War II.

The remarkable courage demonstrated by these proud African-American soldiers in the face of fierce combat, extreme discrimination in the Army, deadly violence from civilians and repressive Jim Crow laws continues to inspire us today.

–nmaahc.si.edu