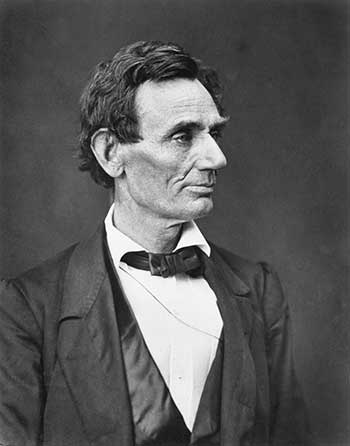

President Lincoln’s General Orders No. 100, also known as the Lieber Code of 1863, set clear rules for engaging with enemy combatants. But the code also clarified how Union soldiers should treat civilians, and in particular women. Largely forgotten today, the Lieber Code established strict laws regarding an issue that was everywhere and nowhere in the consciousness of the Civil War: wartime rape.

Three articles under Section II declared that soldiers would “acknowledge and protect, in hostile countries occupied by them, religion and morality; strictly private property; the persons of the inhabitants, especially those of women” (Article 37); that “all robbery, all pillage or sacking, even after taking a place by main force, all rape, wounding, maiming, or killing of such inhabitants, are prohibited under the penalty of death” (Article 44); and that “crimes punishable by all penal codes, such as … rape, if committed by an American soldier in a hostile country against its inhabitants, are not only punishable as at home, but in all cases in which death is not inflicted the severer punishment shall be preferred” (Article 47).

President Lincoln’s General Orders No. 100, also known as the Lieber Code of 1863, set clear rules for engaging with enemy combatants. The Lieber Code established strict laws regarding an issue that was everywhere and nowhere in the consciousness of the Civil War: wartime rape.

Together the articles conceived and defined rape in women-specific terms as a crime against property, as a crime of troop discipline, and as a crime against family honor. Most significantly, the articles codified the precepts of modern war on the protection of women against rape that set the stage for a century of humanitarian and international law.

Such explicit prohibition was necessary, because even after the code was in place, sexual violence was common to the wartime experience of Southern women, white and black. Whether they lived on large plantations or small farms, in towns, cities or in contraband camps, white and black women all over the American South experienced the sexual trauma of war.

Union military courts prosecuted at least 450 cases involving sexual crimes. In North Carolina during the spring of 1865, Pvt. James Preble “did by physical force and violence commit rape upon the person of one Miss Letitia Craft.” When Perry Holland of the 1st Missouri Infantry confessed to the rape of Julia Anderson, a white woman in Tennessee, he was sentenced to be shot, but his sentence was later commuted. Catherine Farmer, also of Tennessee, testified that Lt. Harvey John of the 49th Ohio Infantry dragged her into the bushes and told her he would kill her if she did not “give it to him.” He tore her dress, broke her hoops and “put his private parts into her,” for which he was sentenced to 10 years in prison. In Georgia, Albert Lane, part of Company B, in the 100th Regiment of Ohio Volunteers, was also sentenced to 10 years because he “did on or about the 11th day of July, 1864 … upon one Miss Louisa Dickerson … then and there forcibly and against her will, feloniously did ravish and carnally know her.”

Black women were in even more danger. Rape was one of the many horrors of slavery, though whites rarely recognized it as such. Interestingly, it was only in the context of war that Southern whites for the first time were forced to acknowledge the rape of black women. In the spring of 1863, John N. Williams of the 7th Tennessee Regiment wrote in his diary, “Heard from home. The Yankees has been through there. Seem to be their object to commit rape on every Negro woman they can find.” Many times, troops and ruffians raped black women while forcing white women to watch, a horrifying experience for all, and a proxy rape of white women. B. E. Harrison of Leesburg, Va., wrote a letter to President Abraham Lincoln complaining that federal troops had raped his “servant girl” in the presence of his wife. Gen. William Dwight reported, “Negro women were ravished in the presence of white women and children.” Just as the rape of white women implied that Southern men were unable to protect their mothers, wives and daughters, the rape of slave women told whites they could no longer protect their property.

A close examination of cases involving the rape of black women reveals that, while black women may have been particularly vulnerable to wartime rape, the Lieber Code brought them for the first time under the umbrella of legal protection. In fact, some black women were able to mobilize miltary law to their advantage.

In the summer of 1864, Jenny Green, a young “colored” girl who had escaped slavery and sought refuge with the Union Army in Richmond, Va., was brutally raped by Lt. Andrew J. Smith, 11th Pennsylvania Cavalry. Thanks to the Lieber Code, though, she was able to bring charges against him, and even testify in a military court. “He threw me on the floor, pulled up my dress,” she told the all-male tribunal. “He held my hands with one hand, held part of himself with the other hand and went into me. It hurt. He did what married people do. I am but a child.” The idea that a former slave, and an adolescent girl at that, could demand and receive legal redress was revolutionary. Despite his attorney’s argument that Green had consented, Smith was discharged from the Army and sentenced to 10 years of hard labor.

This was not an isolated instance or a random judge’s opinion. The effect of the Lieber Codes was almost immediate, as was agreement on the part of high-ranking officials. In reviewing Smith’s sentence, Gen. Benjamin Butler – notorious for his Women’s Order in New Orleans that threatened rape of women who resisted occupation by insulting Union soldiers – supported the guilty verdict. In summarizing the case, he explained, “A female negro child quits Slavery, and comes into the protection of the federal government, and upon first reaching the limits of the federal lines, receives the brutal treatment from an officer, himself a husband and a father, of violation of her person.”

Unwilling to entertain pleas for mercy on Smith’s behalf, Butler declared the officer lucky to walk away with his life. “A day or two since a negro man was hung, in the presence of the army, for the attempted violation of the person of a white woman,” he argued. “Equal and exact justice would have taken this officer’s life; but imprisonment in the Penitentiary for a long term of years, his loss of rank and position — if that imprisonment be without hope of pardon, as it should be — would be almost an equal example.” Abraham Lincoln also reviewed the case and wrote, “I concluded” to let Smith “suffer for a while and then discharge him.”

Southern women’s wartime diaries, court martial records, wartime general orders, military reports and letters written by women, soldiers, doctors, nurses and military chaplains leave little doubt that, as in most wars, rape and the threat of sexual violence figured large in the military campaigns that swept across the Southern landscape. Nonetheless, the Lieber Code made it possible for women to seek justice in military courts and eventually established the modern understanding of rape as a war crime.

Crystal N Feimster is an assistant professor at Yale and the author of “Southern Horrors: Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching.” She is writing a book on sexual violence and the Civil War.