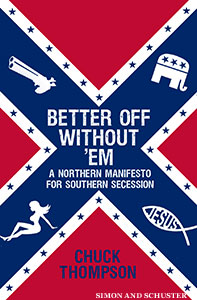

Editor’s note: Following is an excellent review from the Wall Street Journal of the South-bashing book “Better Off Without ‘Em, a Northern Manifesto for Southern Secession” by Chuck Thompson, Simon and Schuster, 312 pages, $25.

By Barton Swaim

Willie Morris, the longtime editor of Harper’s magazine and a native Mississippian, told a story about getting into a cab in New York with the poet James Dickey. The cabbie, recalled Morris, “proceeded to launch into a tirade against our black brethren, and a vicious thing it was, the likes of which I never heard in the Mississippi delta.” It was Dickey, a South Carolinian, who spoke up first: “If there’s anything I can’t stand it’s an amateur bigot.”

The cabdriver made a whole series of assumptions about the two men, merely from their accents, and Dickey’s remark came to mind many times as I read “Better Off Without ‘Em,” Chuck Thompson’s diatribe against the backwardness, reactionary politics and manifold perversity of the American South.

On the first page, the author wonders why the American electoral system must be “held hostage by a coalition of bought-and-paid-for political swamp scum from the most uneducated, morbidly obese, racist, morally indigent, xenophobic, socially stunted, and generally ass-backwards part of the country.” You expect him to let up, to turn the argument around, to look at the other side of question. But he never does. For more than 300 pages, Mr. Thompson travels through the South observing customs, outlooks and people and subjecting them to an unremitting stream of denunciations.

“A Northern Manifesto for Southern Secession,” says the subtitle. Although Mr. Thompson tries hard (often too hard) to be funny, he doesn’t seem to be joking about secession: He really does want the U.S. to be rid of the South.

Now, the South—I say this as a Southerner myself—ought to be fertile territory for any writer with even a modest talent for exposing inanities. From “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer” (1876) to the Englishman Nick Middleton’s “Ice Tea and Elvis” (1999), the American South has provided writers of satire with a ready source of targets: genteel hypocrites, proud ignoramuses, religious fraudsters. But unlike others from outside the South who have written about it—think of Jonathan Raban’s marvelous “Old Glory” (1981) or V.S. Naipaul’s “A Turn in the South” (1989)—Mr. Thompson didn’t set out on his travels to discover things he didn’t know before. He went to see the ridiculous and dreadful things he knew would be there, which is a different approach altogether.

In six essay-like chapters—on the South’s religion, politics, race relations, public education, economic policies and its obsession with, as he thinks, the region’s overrated college football teams—Mr. Thompson tries to show that the American South is so culturally detached from the rest of America as to constitute what really ought to be its own country. He deserves some credit, in these days of lazy punditry, for actually traveling to the places he writes about: Memphis; Columbia, S.C.; Athens, Ga.; Mobile, Ala.; Little Rock; and a lot of little places in between. But typically he just makes a beeline for some small-town gathering, a church or a bar, finds someone with cranky opinions, gets into an argument about politics or religion, and—at least in his own retelling—slays his opponent.

At a Baptist church in west Mobile, for instance, he meets a middle-age man named Marvin, who “starts vomiting out the FOX ‘News’-approved righty line.” He gives us several pages of dialogue between himself and Marvin, a “birther,” and from this we are to understand that the South contains stupid, unreasonable people. At a gift shop in rural Alabama, he meets a kindly old woman named Emma who is convinced—not altogether without reason, it has to be said—that China has bellicose intentions toward the United States. “Emma . . . tells me that China has a one-million-man army currently sitting on a Caribbean island ‘just waiting.'” When Mr. Thompson queries her—”Which island? Waiting for what?”—he notes with satisfaction that “Emma can’t answer.”

You begin to sense that something is seriously awry when the author, evidently unable to find enough cranks and simpletons to fill out a whole book on the South, keeps looking beyond the Confederacy’s borders for material. First he zings House Speaker John Boehner for some offense. Isn’t Rep. Boehner from Ohio? Yes, from Cincinnati, but that’s just across the Ohio River from Kentucky, so he counts as a Southerner. We hear about a public-school teacher who urges his students to believe the Bible infallible. This takes place in Cleveland, but because the teacher had once attended a seminary in Kentucky, it’s an instance of Southern “biblical literalism” infecting the entire country. Mr. Thompson derides U.S. Rep. John Shimkus for citing Genesis as a reason not to worry about global warming. Isn’t Mr. Shimkus from Illinois? Yes, but he is from “an area of southern Illinois settled almost entirely by farmers from Kentucky.” By the book’s halfway point, it’s clear that Mr. Thompson’s problem with Southerners isn’t that they are insular, angry or prone to illusions. It’s that, with exceptions, their political views are insufficiently left-wing.

The author taunts Southerners for their suspicion of “book larnin,'” but there ain’t much evidence of book larnin’ in “Better Off Without ‘Em.” It’s not just the occasional factual error (Atlanta was not burned on Sherman’s March to the Sea, but months before it began). It’s that, while he refers repeatedly to “my research,” the vast majority of endnote citations are Web addresses. He has consulted a few books, among them W.J. Cash’s celebrated indictment of Southern culture, “The Mind of the South” (1941); James Cobb’s excellent recent book on Southern identity, “Away Down South” (2005); and Edmund Wilson’s “Patriotic Gore” (1962). But he quotes from these in ways that make you wonder if he has read or understood them. Wilson, for example, a native of Red Bank, N.J., he calls a “famed southern literary critic”; and a quotation about the South’s “illusions, fantasies, and pretensions,” drawn from C. Vann Woodward’s book “The Burden of Southern History,” means the opposite of what Mr. Thompson says it means.

Mr. Thompson spends most of the book looking for easy targets and finding them. He faces more difficulty when he seeks out Mr. Cobb, a professor at the University of Georgia, and sits in on a class on Southern history. What if the South seceded? Well, for starters, says Mr. Cobb, “You guys might be putting up a Berlin Wall because you’re losing so many people.” That’s not as far from a joke as might at first appear: My own state, South Carolina, is projected to grow by a million people, or about 20%, over the next decade. “Why is it all these people from other parts of the country decide to move to the South?” Mr. Cobb asks the author.

Mr. Thompson changes the subject. Like Emma, the elderly lady in the gift shop, he can’t answer.

You begin to sense that even Mr. Thompson realizes many of his arguments are tendentious. But there’s one thing, he seems to think, that is irrefutable evidence of the South’s moral wretchedness: its racism.

He is outraged, for example, to discover the close proximity of poor black and middle-class white neighborhoods in Southern cities. Of course, he is hardly the first outsider to notice it. Naipaul, in “A Turn in the South,” recalls riding in a car with a black woman near Greensboro, N.C.: “Hetty knew the land well,” he writes. “She knew who owned what. It was like a chant from her, as we drove: ‘Black people there, black people there, white people there. Black people, black people, white people, black people. All this side black people, all this side white people.” The intermingling of black and white neighborhoods can unsettle an outsider, true enough. Still, it’s not obvious to me that this is more reprehensible than the way in which many American cities outside the South contain vastly populated areas of racial uniformity.

Here’s how Mr. Thompson treats the same subject: In Laurens, S.C., he’s shown the street that “where stately, well-manicured ‘Southern Living’ mansions become Tijuana in the time it takes to run a red light.” Places like Little Rock and Memphis, he says, “are arranged along the lines of Third World horror shows; wide streets lined with opulent, plantation-style homes sitting just around the block from apocalyptic Negro wastelands.” Leave aside Mr. Thompson’s rather too superior descriptions of poor black neighborhoods (did he really use the term “Negro”?). More disturbing is his refusal to take seriously any evidence that Southern racism has diminished, even when that evidence comes from African-Americans themselves.

He is aware of reports in the New York Times and elsewhere that black Americans are moving to the South in record numbers. A black New York native living in Oxford, Miss., tells him, “I love it here.” But Mr. Thompson dismisses what he calls “breathless predictions of a post-racial South.” They just make him look harder for racism—and of course he finds it. He makes his way to the Redneck Shop in Laurens, a place that openly sells white supremacist paraphernalia.

It would be foolish to suggest that racism is no longer a problem in the South. It is. But you aren’t likely to shed light on it by seeking out feeble-minded Klansmen or by Googling “racism + the south.” An observer, outsider or not, must keep his mouth shut and watch and listen for days, weeks; and although the results may be fragmentary and tentative and won’t lend themselves to wholesale denunciations, they are truer to life—and often more damning. Here is Jonathan Raban in “Old Glory,” the story of his journey down the Mississippi, as he describes visiting two black neighborhoods in Memphis, Hollywood and Chelsea In Watts, Roxbury, Harlem, South St. Louis, I’d felt the angriness in the air . . . It wasn’t so in Hollywood and Chelsea. . . . They must have been angry; they had every excuse for anger.

Yet it was an anger which hadn’t yet crystallized into that automatic hatred of the white stranger which I had met in the ghettos of the North; or at least, the hatred was elaborately masked. I received the odd curious glance, accompanied by a faint smile, as if I’d lost my way and needed street directions to get me home. Several times people went out of their way to make me welcome. Stay and talk. Stay and see.

There is no sense in Mr. Raban’s narrative that he is trying to prove anything: He simply recounts what he sees, with painful accuracy. He has no point to make. Mr. Thompson, by contrast, has nothing but points to make: hundreds and hundreds of them.

Yet for all his know-it-all wit, the author is never able to answer some of the most obvious responses to his secessionist argument. Who would serve in the U.S. military, currently constituted disproportionately of Southerners, who fight and die not for the Confederate flag but for the American one? What would be done with Northern enclaves like Chapel Hill and Atlanta? And—as a University of Georgia student asks Mr. Thompson near the end of the book—”If you don’t have the South to look down on, who would you look down on?”

—Mr. Swaim, who writes about electronic books for the Journal,

is the author of “Scottish Men of Letters and the New Public Sphere.”

A version of this article appeared August 11, 2012, on page C5 in the U.S. edition of The Wall Street Journal, with the headline: A New Turn in the South.