The waves off North Carolina’s Cape Hatteras rose 20 feet and crashed down on the steam-powered vessel, which at just 172 feet long appeared too small to be a warship. Many of the 63 sailors on the USS Monitor had been in storms before, but they were used to wooden ships that would ride the waves instead of bucking under them, taking a beating like this one. All the Monitor Boys, as they were called, had volunteered to serve on the Union’s experimental vessel, with its ironclad hull and peculiar raftlike weather deck that rose just 18 inches above the sea. The design deprived enemies of surface area at which to aim by placing all of the ship’s systems and living quarters completely below water level for the first time.

Instead of conventional cannons, the Monitor was armed with twin 11-inch Dahlgren smoothbore shell guns mounted inside a rotating turret, a novel design that allowed the crew to fire in any direction without turning the ship.

Some of the men had served on the Monitor when it made its debut in Virginia at the Battle of Hampton Roads, just nine months earlier. On March 8 and 9, 1862, the Confederates attempted to break the Union blockade of the James River with their new weapon, the ironclad CSS Virginia. The converted warship outfitted with iron plates was a restored wooden steam frigate previously known as the USS Merrimack.

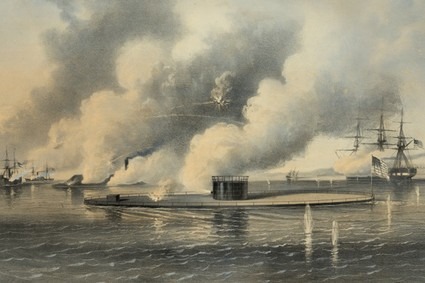

On the first day of the battle, the Virginia had destroyed two wood-hulled Union warships. By the second day, the Confederate vessel was moving in on the defenseless USS Minnesota, which had run aground, when the little Monitor arrived to intercept the Virginia before it could move in for the kill. The two ironclads fired at each other at close range for hours. Though the Monitor was some 100 feet shorter and 3,500 tons lighter, it fought the Virginia to a draw. The battle would attract widespread news coverage and help lead to the demise of wood-hulled ships in navies around the world.

The Monitor itself became a household name and its crew instant celebrities. President Lincoln went aboard at least once, and women lined up to tour the celebrated vessel when it was in port.

After its dramatic showing at Hampton Roads, the Monitor kept guard over the Chesapeake Bay and made forays up the James River, where the crew suffered more from heat and mosquitoes than the occasional sharpshooters who attempted to pick off crewmen on the wide-open deck.

Though the Monitor had shown its toughness in battle, it had a significant weakness: It wasn’t particularly seaworthy. The ship had almost capsized during two storms on its first trip from New York City to Hampton Roads. On Dec. 30, 1862, the Monitor would have to survive the open ocean again while being towed by the steamer USS Rhode Island toward Beaufort, N.C. Gale-force winds battered the ship in a violent storm. As the Monitor passed the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse in the late afternoon, the crew could see that the giant waves were weakening the caulking around the base of the metal turret. The ship began to take on water despite the crew’s efforts to stay ahead of it with their bilge pumps.

Still, William Keeler, the ship’s paymaster, would describe an almost festive scene in a later letter to his wife. “At 5 o’clock p.m. we sat down to dinner, every one cheerful & happy & though the sea was rolling & foaming over our heads the laugh & jest passed freely ’round; all rejoicing that at least our monotonous, inactive life had ended & the ‘gallant little Monitor’ would soon add fresh laurels to her name.”

But the sea kept up its relentless assault. Around 11 p.m., the crew hoisted a red lantern on top of the turret—a signal of distress. The Rhode Island immediately sent boats to pick up the Monitor’s panic-stricken men. Some were swept off the deck while trying to reach the rescue boats. A few leaped off the ship only to miss and land in the cold Atlantic. Other men, paralyzed with fear, refused to try for the boats.

The Monitor finally sank around 1 a.m. on December 31. Twelve sailors and four officers would lose their lives. Periodicals likeHarper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper would later publish artists’ renderings and poems about the tragedy, but for families of the victims there was little solace. The exact location of the Monitor’s final resting place and the crewmen who perished would remain a mystery for more than a century.

In 1973, a team of scientists from the Duke University Marine Laboratory launched a two-week mission to find the Monitor. In his 2012 book USS Monitor: A Historic Ship Completes Its Final Voyage, John Broadwater describes how, on the night of Aug. 27, 1973, the team’s electronics engineer noticed a black squiggle on the ship’s fathometer, a sonar instrument used to measure the depth of water beneath a ship. Using side-scan sonar equipment, the team collected acoustic images and video of what lay 230 feet beneath them. The following year, an analysis of the wreck by a U.S. Navy research vessel, equipped with the most advanced high-resolution deep-water imaging technology, confirmed that the Duke team had indeed discovered the Monitor wreck approximately 16 nautical miles south-southeast of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse.

Over the next three decades, researchers would mount a number of diving expeditions to further study the wreck. In 2002, the Navy and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) successfully raised the turret to the surface, leaving the rest of the ship to be studied where it lay. Many of the turret’s contents were intact, including the Dahlgren guns, a high-quality wool coat, a jar of relish, and pieces of silverware engraved with the sailors’ names. There were also two skeletons.

Broadwater, former chief archaeologist at NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, was the first scientist to enter the turret after it was lifted onto the expedition barge. It was wet and eerie inside like a cave, he recalls, with water dripping down on sediment, sand, lumps of coal, and more than a century’s worth of iron concretion. Broadwater saw the first set of remains immediately. “It looked like the poor guy had almost made it to the exit hatch,” he says. “It was very moving.” The second set of remains would be discovered by Broadwater and his team several weeks later.

To identify the two sailors, the archaeologists sent the remains to the U.S. Joint Prisoners of War/Missing in Action Accounting Command’s Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii for analysis. “It’s very important to give identities to these war heroes,” says Broadwater.

John Byrd, director of the laboratory, says that “sunken ships can be a very, very good environment for preserving remains” because of the protective coating of silt that forms over them. This was the case inside the Monitor, where tons of coal mixed with the silt, creating an anaerobic environment that prevented chemical reactions and animal activity from destroying the skeletons.

Using the latest forensic technology, Byrd’s team was able to create biographical profiles of the two sailors. HR-1 (Human Remains 1), the man Broadwater believed had nearly made it through the hatch, was estimated to have been between 17 and 24 years old and about 5 feet, 7 inches tall. Analysis of the skull showed that the young sailor had good hygiene and a broken nose that was healing.

The forensic team estimated that HR-2 could have been as tall as 5 foot, 8 inches, was between 30 and 40 years old, and, judging by the dent in his teeth, likely smoked a pipe. The sailor suffered from arthritis and had an asymmetrical leg. Both men were white (three of the 16 crewmen who perished were African-American).

Lisa Stansbury, a genealogist contracted by NOAA, has been working to identify the two sailors. She has matched the information from the forensic analyses with biographical records, including medical logs from other ships where the men had served, to narrow the 16 missing sailors down to just a few candidates. Stansbury believes a 21-year-old seaman named Jacob Nicklis from Buffalo, N.Y., could be HR-1. He is on the shortlist of men who fit the age, height, and racial profile, as determined by Byrd’s team. The second sailor could be Robert Williams, a first class fireman in his early 30s, who was born in Wales and joined the U.S. Navy in 1855. His medical records are consistent with some of HR-2’s conditions.

Scientists believe that further testing, including isotopic analysis, could provide information about where the victims were born. Because chemical signatures of food and water consumed during the first years of a person’s life are preserved in tooth enamel, traces that are distinctive to a geographic region (like a diet of corn or grain) can provide important clues. Since half of the Monitor’s crewmen were immigrants from Europe, mostly Ireland, this information could further narrow the list of candidates. Byrd says researchers at the Smithsonian Institution have expressed interest in performing this testing on the sailors’ remains.

In March 2012, Louisiana State University’s Forensic Anthropology and Computer Enhancement Services Laboratory unveiled sculptures of the two sailors’ faces, reconstructed from casts of their skulls using 3-D clay, computer-generated modeling, and computer-enhanced imaging techniques.Experts immediately noticed that the second sailor’s reconstructed face strongly resembled a man in a group photo of the Monitor crew who had been identified by a survivor as Robert Williams. The first man, however, didn’t appear to bear much resemblance to a photo given to U.S. News by William Ferry, Nicklis’s great-great-nephew.

A definitive identification will be possible only if the ArmedForces DNA Identification Laboratory at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware can match the mitochondrial DNA extracted from the recovered remains to a maternal relative of each sailor. Stansbury has sifted through military logs, census records, and pension files, but was not able to locate any Williams family members.

Nicklis’s great-great-nephew, Ferry, says he is willing to be tested for a DNA comparison. However, it is unclear when this might happen, as the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command has a backlog of about 750 active cases, mostly from the Korean War.

Even without a positive identification, says David Alberg, superintendent of NOAA’s Monitor National Marine Sanctuary, which encompasses the ship’s final resting place, it’s time to put the sailors to rest. December 31 will mark 150 years since the warship capsized, and Alberg says it would be the perfect occasion to honor the 16 lost Monitor Boys with a ceremonial interment of the remains, preferably at Arlington National Cemetery.

“Arlington is the place where the nation has always buried its heroes,” Alberg says.

“These men are heroes.”

He has petitioned the secretary of the Navy to release the remains. Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairshas approved the first official monument honoring the Monitor Boys. Alberg says it will be dedicated on December 29 at Hampton National Cemetery in Virginia, not far from where the famed ship first made history.

-Karl Zalan, U.S. News & World Report