The names of the epic Civil War land battles—Bull Run, Shiloh, Antietam, Chancellorsville, Vicksburg, Gettysburg, and Chickamauga—have a certain ring to them. Even the term “Sherman’s March to the Sea” is evocative. In contrast, there is little that reverberates in the names of the Civil War’s naval actions, which include the Battles of Fort Henry, Fort Donelson, Island 10, Fort Sumter, and Mobile Bay, as well as the occupation of New Orleans.

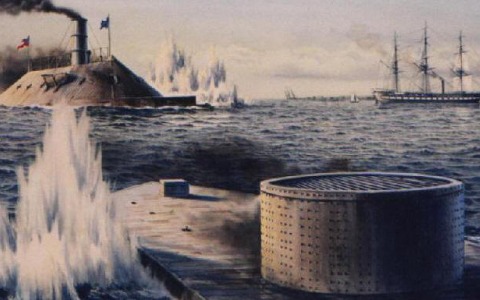

Yet knowledge of the naval component of the Civil War is crucial for a number of compelling reasons. Arguably the foremost is that it’s essential in determining how that war was lost by the Confederacy and won by the Union. There’s also the matter of the unusual number of technological advances in naval warfare that occurred during the war between the states, including steam propulsion, ironclad hulls, screw propellers, rifled cannons, explosive shells, rotating gun turrets, submersibles, and naval mines. And those technological advances did more than reshape the naval combat of the Civil War; they significantly expanded the ways that naval power would be employed in the future.

In a broader context, the naval component of the Civil War is also a unique chapter of the full narrative of American maritime power. In that perspective, it serves as a historical bridge, connecting the United States’ stunning advance as a major maritime nation during the War of 1812 to the sweeping seapower concepts personified by Rear Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan and President Theodore Roosevelt at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century.

Enter James McPherson’s exceptionally well-illustrated descriptions of the Civil War’s major naval events. Covered with relevant detail and clarity, these events include: the Union’s blockading of the Confederacy’s Atlantic

and Gulf coasts and the resulting blockade-running by the South; the commerce-raiding of Confederate privateers and such legendary ships as the CSS Alabama, CSS Florida, and CSSShenandoah; and the exhausting and complex warfare fought on the river networks that marked the geography of the Confederate states.

There are also well-detailed descriptions of specific combat actions, such as the series of Union Navy actions on the lower Mississippi River that resulted in the capture of New Orleans early in the war, and the Battle of Mobile Bay in August 1864, which helped seal the fate of the Confederacy. Between these two historical bookends is a complex and bloody narrative filled with the successes and failures of both sides, and the many lessons learned by a still-young United States.

Of particular interest is the important but often neglected connective tissue between the main events of the war. That connective tissue includes such diverse elements as international trade, interservice rivalry between the Union’s Army and Navy, the potential and actual involvement of Great Britain, France, and other nations, and the oft-overlooked but significant influence of geography. And, by way of connective tissue, McPherson consistently illuminates how key military and civilian leaders influenced the war’s storyline. In the second paragraph of his introduction, for example, McPherson presages his dedication to recognizing the importance of key players with a strong (and, for many, surprising) opinion about the Union’s Admiral David Glasgow Farragut:

Farragut’s victory at Mobile Bay and his even more spectacular achievement in the capture of New Orleans in April 1862, plus the part played by his fleet in the Mississippi River campaigns of 1862 and 1863, did indeed entitle him to equal status with Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman in winning the war.

Another key leader, in this case a civilian, was Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, who served in that job from March 1861 until March 1869. During his tour he became known for his management skills and for refusing to rely on seniority when making key appointments. Early in his study, McPherson describes the secretary:

Welles’s naval experience was limited to a two-year stint as the civilian head of the Bureau of Provisions and Clothing during the Mexican-American War. A long career as a political journalist in Connecticut had given little promise of the resourceful administrative capacity he would demonstrate as wartime secretary of the navy.

Later, McPherson leaves no doubt about Welles’s important role in the Union’s victory, and his strength of character in standing up to public criticism:

This buildup of what was by 1865 the world’s largest navy was an extraordinary achievement, for which Gideon Welles deserves much of the credit. An excellent administrator who put in long hours at his desk, Welles endured recriminations by merchants whose ships and cargoes fell victims to the [Confederate commerce raider] Alabama or other raiders and indictments by the press for the escape of runners through the blockade. Welles eschewed public responses to these accusations, confining his comments to his diary and retaining the full confidence of President Lincoln.

Interestingly, this description of Welles puts one in mind of William Jones, secretary of the Navy during the War of 1812. Jones served in that job from January 1813 to December 1814 and, as was the case with Welles, his administrative skills were an essential part of the Navy’s successes during wartime. Neither man was charismatic or a great strategic thinker; both were, however, exceptional managers, and they brought what turned out to be essential skills to their job. In the process, they also helped shape the job description for naval secretaries to come.

As an extension of his attention to the principal players of the war, McPherson weaves such details as political infighting within the Union Navy into his work. At one point, for example, he describes the internal disputes surrounding the ineffective leadership of Rear Admiral Samuel Francis Du Pont while that officer led attacks against Charleston. Following extended infighting, Du Pont was eventually replaced by Rear Admiral Andrew H. Foote, who early in the war had led a successful gunboat attack against Fort Henry on the Tennessee River.

As part of his emphasis on persons and personalities, McPherson also includes instances of Army-Navy discord, which was a constant in the conflict. A noteworthy example involved the Union’s attempts to take Charleston in July 1863. At the time, Rear Admiral John Dahlgren was the newly appointed commander of the Union’s South Atlantic Squadron. Dahlgren immediately began planning a joint Army-Navy operation against Charleston with Major General Quincy Gillmore, and their cooperation was initially exemplary.

The first phase of the Charleston operation involved landing troops at the south end of Morris Island and then moving north against two artillery fortifications, Battery Wagner and Battery Gregg, both of which overlooked the outer Charleston Harbor entrance. The Army troops were supported by fire from the guns of four Navy ironclads, and when the initial assault against the two batteries was repulsed, the attack evolved into a siege. After weeks of hammering by Dahlgren’s naval gunfire, the defenders eventually evacuated the batteries and the positions were taken by General Gillmore’s troops. It was a significant Army-Navy operation that, for all practical purposes, closed the port of Charleston. It was also an example of how a joint Army-Navy operation could (and should) be run, while co-incidentally demonstrating the effective use of naval gunfire support for an Army ground operation.

The logical next phase at Charleston was an attack on Fort Sumter, and that turned out to be a different story. Independently, Dahlgren and Gillmore planned amphibious assaults against the fort on the night of September 8. When each learned of the other’s plan just hours before the attacks were to begin, there was a serious lack of the cooperation that had marked the Morris Island operation.

The argument was based on whether the assault would be led by the Army or Navy. The dispute was not resolved, and the Navy attacked first with a combination of sailors and Marines; it was repulsed. Observing the Navy’s failed effort, Gillmore called off the Army assault. There were no further major attempts to capture Charleston, and as it turned out, none was necessary. The port had been effectively closed to blockade runners by the previous Army-Navy actions. As McPherson puts it, “the capture of the city would be merely symbolic and not worth the cost.”

Following the Union Navy’s successes at the Battle of Mobile Bay—known for Admiral Farragut’s order from his flagship USS Hartford, “Damn the torpedoes [the term used at that time for mines]. Full speed ahead!”—the naval component of the Civil War drifted to an end. The Union Navy’s work was, overall, well done: Despite the fact that more than 90 percent of the Confederate blockade runners’ efforts were successful, the Union Navy had maintained a blockade of the Confederacy that was effective enough to cripple the South’s war effort. The war on the Mississippi and other rivers was also an overall success for the Union Navy, which became the enabler afloat for the Union Army.

“To say that the Union Navy won the Civil War,” writes McPherson, “would state the case much too strongly. But it is accurate to say that the war could not have been won without the contribution of the navy.”

With the end of the Civil War, the U.S. Navy’s sights quickly shifted away from an inward and coastal focus, and seapower in its blue-water sense became firmly implanted in the national psyche. The naval component of the Civil War had been a pivot point that assured fulfillment of a prediction made by John Paul Jones in 1778. At that time, Jones—not generally considered a seapower visionary—wrote to a friend who was pessimistic about the progress of the War of Independence and the state of the Continental Navy:

Our Marine [Navy] will rise as if by enchantment, and become within the memory of Persons now living, the wonder and envy of the World.

Jones might have been a bit off in his timing, but he was spot-on with the balance of his prediction. As the smoke cleared from the Civil War, the U.S. Navy’s sights were fixed on far horizons.

Joseph F. Callo is the author of John Paul Jones: America’s First Sea Warrior.